China wants to redefine democracy

As the Chinese government tells it, China is a thriving, functioning, and successful democracy—everything, it argues, that the US is not.

As the Chinese government tells it, China is a thriving, functioning, and successful democracy—everything, it argues, that the US is not.

Over the weekend (Dec. 4-5), the central government published a 55-page white paper extolling the virtues of its democracy, followed by a report the next day on the terminal malaise of US democracy. The main takeaway from those two texts, that China is more democratic than the US, conveniently comes just days before US president Joe Biden’s Summit for Democracy, to which China has not been invited (though Taiwan has).

“China’s efforts to redefine democracy are part of its wars of influence,” said Sun Peidong, a professor at Cornell University researching the social and cultural history of post-1949 China.

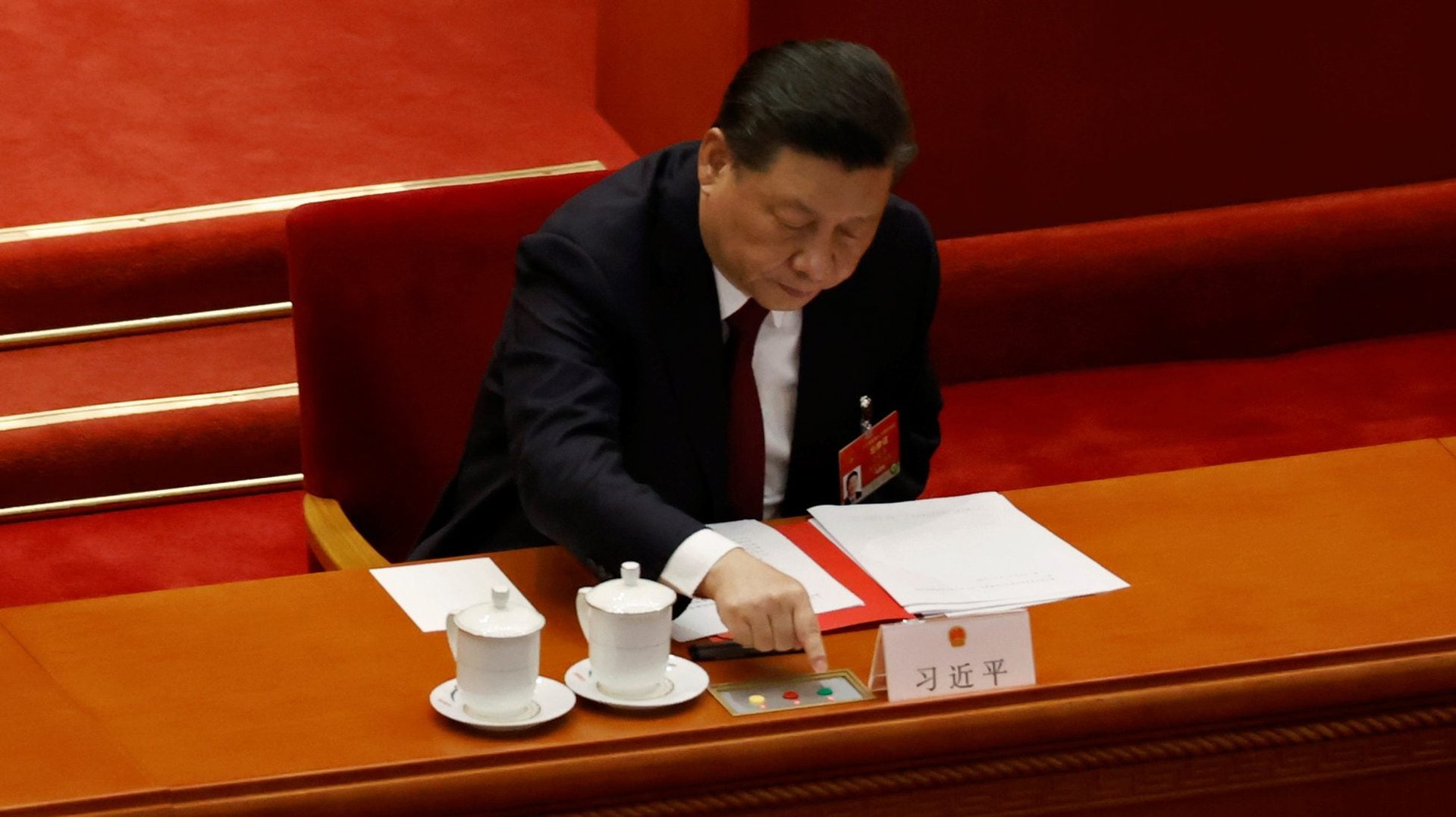

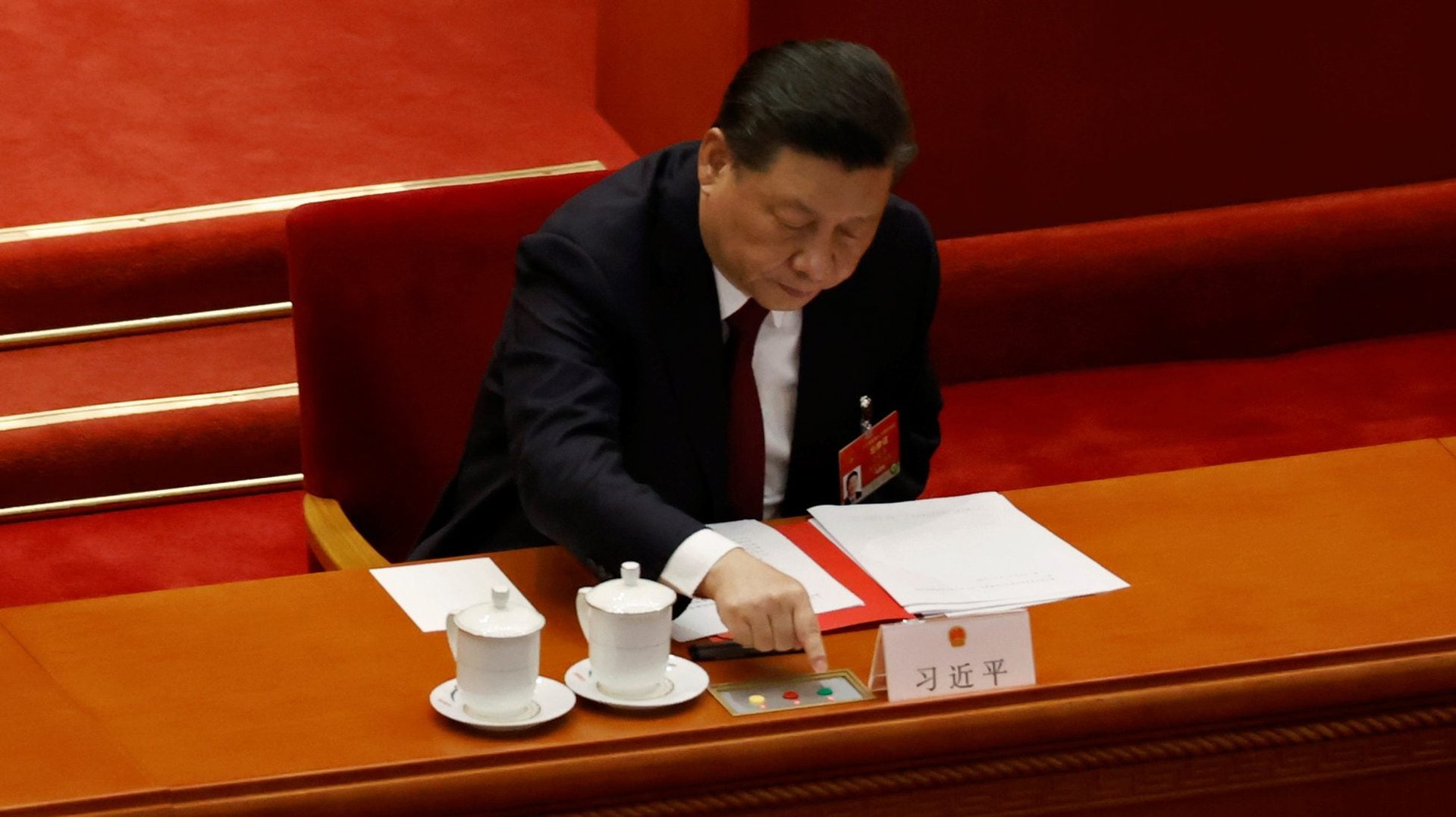

She quoted a 2015 speech (link in Chinese) by Chinese leader Xi Jinping: “If you’re backward, you’ll be beaten up; if you’re poor, you’ll have to starve; if you can’t speak, you’ll get a scolding.” For China, pushing its own version of democracy is a bid to win authority and silence critics, “to win minds and hearts,” Sun said.

How does China define “democracy”?

The conventional, widely accepted definition of liberal democracy prioritizes competitive, free, and fair elections; freedom of expression; and freedom of the press. How then can one-party ruled China, where the top leadership is chosen in an opaque process by Communist Party members, and where expression is severely restricted, stake a claim to being democratic?

First of all, by disagreeing that a democracy must have all of the above features, or that there can even be a universally agreed upon definition of the system. “There is no fixed model of democracy; it manifests itself in many forms,” says the white paper, adding that insisting on one definition is itself “undemocratic.”

China describes its governance system as a “people’s democratic dictatorship,” with “democratic” subsumed under “dictatorship.” In this framing, the state can manifest the people’s will through “consultation,” and without needing to engage in messy processes like direct national elections:

Whole-process people’s democracy integrates process-oriented democracy with results-oriented democracy, procedural democracy with substantive democracy, direct democracy with indirect democracy, and people’s democracy with the will of the state.

The white paper, however, entirely sidesteps questions of how Chinese institutions, like the system of people’s congresses where citizens can theoretically get (pdf) direct political representation, actually work to address fundamental issues like balancing competing interests and resolving disputes—challenges that the US is publicly grappling with right now, said Mary Gallagher, professor of political science at the University of Michigan.

“The white paper…basically ignore[s] that there are really severe conflicts of interest, there’s class conflict, there’s massive inequality” in China too, she said.

China also relies on features of democracy to attack democratic regimes. For example, the foreign ministry’s Dec. 5 report on the “disastrous state” of US democracy cites sources that exist precisely because of liberal democratic freedoms: news outlets like the Wall Street Journal and New York Times (both blocked in China); the broadcaster CNN (frequently censored in China); and the independent pollsters Pew Research Center and Gallup (opinion polling is heavily restricted in China).

Even in critiquing Biden’s Summit for Democracy, a Chinese ministry spokesman reiterated points already made by US papers like the Washington Post.

Using democracy to justify authoritarianism

In a 2018 study, Tsinghua University political scientist Yue Hu examined 50 years’ worth of articles in the party paper People’s Daily and found that “democracy” and its extensions (“democratic,” “democratization) appear in its pages on average 11 times per day.

Why would authoritarian propaganda devote so much time to discussing democracy? The Chinese government, Hu argues, doesn’t reject democracy outright but rather “strategically manipulates the discourse about democracy” to preserve and legitimize authoritarian rule. And with much talk of a “new Cold War” between the US and China, framed in part as an ideological showdown between autocracy and democracy, Beijing has strong incentives to make the case for the supremacy of its political system.

The ideological conflict will be between democracy and authoritarianism—with China being the flagbearer of the latter, said Gallagher. “…So China, by using these words like democracy, is to me really a justification of authoritarianism.”

And China is using the word “democracy” a lot—over 200 times in the white paper, to be exact. But this signals less a genuine engagement with democracy and more that “the CCP is thinking only of maintaining stability and security vis-à-vis the enormous social contradictions at home and intensive tensions against the rest of the world,” said Sun.

What Hong Kong taught Beijing about democracy

The effort to redefine democracy has played out particularly starkly in Hong Kong, where China’s short-lived experiment in allowing civil liberties including free speech and public protest, coupled with limited electoral democracy, eventually led to massive protests in 2019 for genuine competitive elections—to which Beijing has since responded with a withering political crackdown.

Since then the liberties that Hong Kong used to enjoy have been thoroughly dismantled: a major newspaper shuttered; activists and politicians jailed; speech criminalized. Hong Kong activists and protesters, as official thinking goes, “[used] democracy, human rights and freedom as a pretext” to attack China—so those liberties must now be withdrawn for the sake of national security.

Notably, the exiled former Hong Kong lawmaker Nathan Law will speak at Biden’s democracy summit; in response, Hong Kong’s security chief said Law is “using ‘democracy’ as a facade” to spread “political lies.”

Meanwhile, officials have tied themselves into a pretzel as they try to stage manage a sham legislative election this month—the first since a sweeping national security law came into force last July.

The election can’t be too democratic lest “unpatriotic” candidates try to run for office; but it has to at least look democratic enough to keep up the pretense that the city government has any trace of legitimacy left. That has led to comically contradictory statements, with Hong Kong’s chief executive saying low voter turnout suggests public satisfaction with the government, while a veteran pro-Beijing figure has said low turnout suggests “foreign interference” (link in Chinese).

Defining democracy by the outcome

Beijing’s report on democracy makes clear that the government defines democracy based on outcomes, rather than processes: economic growth, success in controlling Covid, a strong and powerful China, etc.—key indicators of what scholars call “performance legitimacy” and what the central government says “all boils down to whether the people can enjoy a good life.”

But what happens if performance slips and life is no longer so good?

“The tricky part is when the definition [of democracy] itself is defined by the outcome, but the outcome is not 100% [controlled],” said Jean Hong, a professor at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology who studies authoritarian regimes. “So when crises come…it becomes entirely the government’s responsibility.”

So far, Beijing appears to have addressed crises effectively and ruthlessly enough to keep an iron grip on power. While some observers had speculated the Covid outbreak could be “China’s Chernobyl,” Beijing’s successful pandemic response has instead given the central government a massive confidence boost about the superiority of its political system.

Chinese citizens appear to feel the same: in ongoing research (pdf) based on analyzing Chinese social media posts, Hong found that as major democratic countries worldwide floundered in their pandemic response, online sentiment about Western democracies turned sharply negative and cynical. Meanwhile, discussions of democratic values in China were more likely to remain positive, even though China’s control of the coronavirus has in large part been thanks to grassroots-level institutions that enable and enforce draconian lockdowns, and intrusive neighborhood surveillance and supervision.

“They get around the criticism [that these institutions aren’t democratic]…by saying, ‘Anything that helps the CCP govern more effectively, that improves people’s livelihoods, is democratic,’” said Gallagher.