Does it matter what we call our teachers? Some academics seem to think so, and have called for the titles “Sir” and “Miss” to be banished from the classroom because they are sexist. Yet their use in the English language, along with “Mr” and “Ms,” is already in decline.

I went to a fairly strict school in the 1980s—uniform, school tie, the cane, having to stand up when a teacher entered the room—where Sir and Miss were de rigueur.

I still remember how odd it was when I was transplanted to university at age 18 and was casually invited to refer to lecturers by their first names. It felt cool and grown up, although it obscured rather than removed the power hierarchy—ultimately these people were still marking our essays and giving us disapproving looks if we didn’t contribute in seminars.

I think, like many children, that while I was at school I wasn’t consciously aware of the sexist disparity between Sir (arise, Sir Galahad) and Miss (don’t arise, unmarried woman). We called all female teachers Miss, even the ones who we knew were married. But neither term is necessarily a mark of respect, especially if the vowel sound is dragged out.

I recall an old French and Saunders sketch where Dawn and Jennifer play two obnoxious teenagers, asking their teacher increasingly personal questions: “Miss, are you a lesbian?” I’m not sure that words themselves mean anything much—it’s the intention behind them that counts more, and some children can be especially adept at making any word into an insult.

Dropped titles

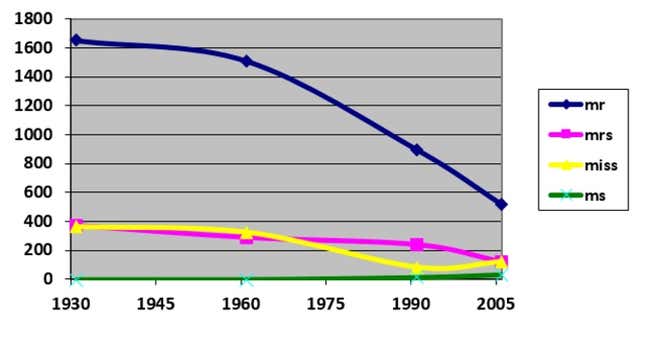

What does appear to be the case is that British society has been gradually dumping its titles over the last century or so. My research has showed that Sir, Mr, Miss, and Mrs have all plummeted in usage in written English, with “Mr” showing the most dramatic falls, as the graph below shows. If the trends continue, in a few decades these terms will be practically obsolete.

We place less emphasis on what’s called negative politeness (marking respect and social distance) and more on positive politeness (showing we’re all mates). Language has become increasingly informal as a result.

One term of address which has shown an increase is Ms but it was starting from nowhere, is still a rarity, and encounters resistance. I’m doubtful it will fully catch on any time soon. If the unequal term of address system is going to be resolved, it will be when we give up terms of address altogether and just use people’s names.

So would that be a good idea in the classroom, where teachers sometimes need to impose control if they are to do their jobs effectively? I’m not so sure all children are able to grasp the subtleties of hidden power hierarchies if we seek to obscure them. They may feel more at liberty to take liberties if they get to refer to their teachers as Sue or Mick.

I don’t like Sir or Miss though—on top of the sexist disparity, they enforce a kind of anonymity onto the profession—with the same nom de plume being used for everyone. It’s almost as bad as “Hey, teacher!”

So if I was in charge of a school, I’d expect pupils, at least up until aged 16 or so, to use Mr. Smith and Miss/Mrs/Ms Jones by default. But ultimately, each teacher knows their own class and what works best and they should be empowered to decide what their charges call them.

Cause for confusion

At my university, the power hierarchy is almost invisible (although it does bubble below the surface). Sometimes this results in weird tensions.

One of my students, who had come from an overseas institution, referred to me as Dr. Baker from the outset of our meetings. It felt odd and wrong, and I hoped she would simply drop it of her own accord when she acclimatized to the university culture. In fact, the culture I work in is so laid back that I felt I would be overly imposing authority on her to instruct her: “Oh, just call me Paul.”

So Dr. Baker continued for the whole term, sounding increasingly incongruous as we got to know each other. When I finally said: “You can call me Paul,” it was like letting the air out of a balloon. She had assumed I liked the title and had kept using it, feeling more and more uncomfortable.

I think the point of that anecdote is that problems arise when people don’t communicate but try to second guess each other instead. One aspect of living in a more informal society should be that we are able to talk to each other more about a wider range of topics. Which can only be good.

So if we do require pupils to use certain terms of address, it could be used as an opportunity for discussion and reflection in the classroom—the concept of respect is more complex than it used to be and it deserves due consideration, rather than being taken for granted.