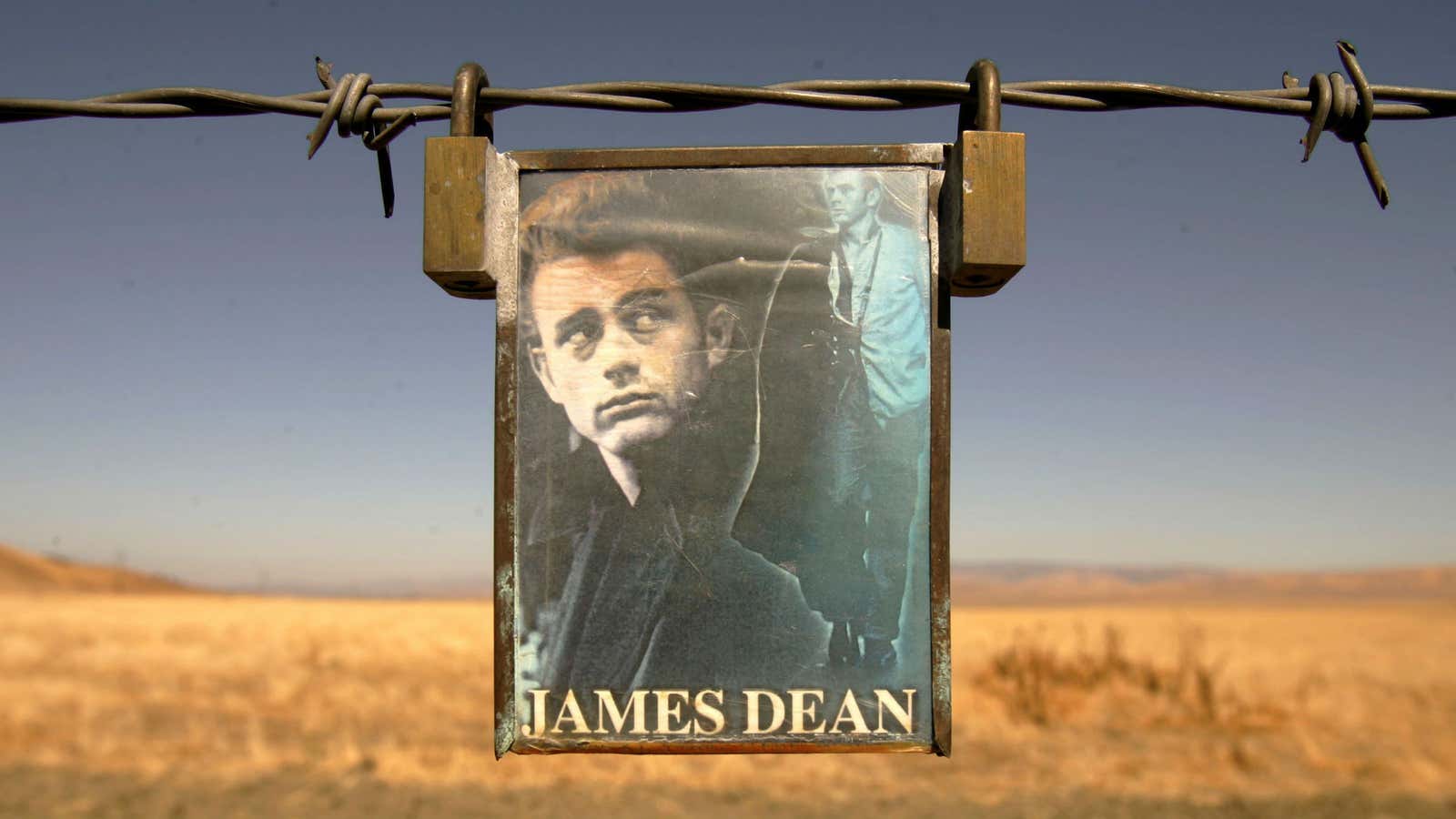

What makes things cool? What penumbral principle explains not only the marketing campaigns of Harley Davidson, Apple, and Dos Equis, but also the appeal of cowboys, James Dean, and Jennifer Lawrence?

A new paper in the Journal of Consumer Research takes a stab at answering what might be an unanswerable question by studying how brands and companies become cool in the eyes of consumers. And, to my surprise, it’s decently plausible.

To understand their theory of cool, compare it to another possibly undefinable concept: humor. What makes something funny? Plato and Aristotle offered what we now call the Superiority Theory. Basically, we laugh at other people’s misfortunes, or when we feel superior. This theory explains physical humor, most of Family Guy, and a joke like this:

A woman gets on a bus with her baby. The bus driver says: ”Ugh, that’s the ugliest baby I’ve ever seen!” The woman walks to the rear of the bus and sits down, fuming. She says to a man next to her: ”The driver just insulted me!” The man says: ”You go up there and tell him off. Go on, I’ll hold your monkey for you.”

But Superiority Theory doesn’t do much to explain why we recognize other jokes as jokes. For example: “There are two fish in a tank; one says ‘How do you drive this thing?'” Puns are funny (some of them, anyway, theoretically) for reasons besides superiority. They need a broader theory. As Shane Snow explained in the New Yorker, academics are coming around to a more sophisticated idea called Benign Violation.

Benign violation means your expectations are subverted—obvious jokes aren’t funny—in a way that poses no threat or sadness to the audience. “A priest and a rabbi walk into a bar and order a beer” isn’t a joke; “a priest and a rabbi walk into a bar and die right there on the floor” isn’t a joke; but “a priest and a rabbi walk into a bar—ouch!” is recognized as a joke (let’s ignore its quality) because it subverts expectations in a way that doesn’t feel menacing. Snow writes:

Benign Violation explained why the unexpected sight of a friend falling down the stairs (a violation of expectations) was funny only if the friend was not seriously injured (a benign outcome). It explained Jerry Seinfeld’s comedic formula of pointing out the outrageous things (violation) in everyday life (benign), and Sarah Silverman’s hilarious habit of rendering off-color topics (violation) harmless (benign) in her standup routines. It explained puns (benign violations of linguistic rules) and tickling (a perceived physical threat with no real danger).

Like humor and beauty, coolness seems to defy definition. The literature tells us that coolness is subjective rather than universal (is U2 cool?), and we know that it changes over time (is smoking cool?). But a new paper by Caleb Warren and Margaret C. Campbell applies a more constrictive definition that proves surprisingly workable: “Coolness is a subjective, positive trait perceived in people, brands, products, and trends that are autonomous in an appropriate way.“

If funny is a benign violation of expectations, cool is a measured violation of malign expectations.

Cool means departing from norms that we consider unnecessary, illegitimate, or repressive—but also doing so in ways that are bounded. The 1984 Apple ad that said, essentially, “you have a choice; don’t buy IBM!” was considered one of the coolest commercials of all time, because it was, in the researchers words, “autonomous in an appropriate way.” But a 1984 Apple ad saying “you have a choice; don’t pay federal income taxes!” wouldn’t be cool, because taxes are legitimate; and a 1984 Apple ad saying “burn IBM’s headquarters to the ground!” wouldn’t be cool, because that’s just overdoing it. Cool requires a bit of Goldilocks.

It also requires something worth rebelling against. In my high school, as in many high schools, one of the clearest ways to show classmates that you were cool was to violate the dress code in clever ways. Isn’t violating a repressive clothing regime sort of inherently cool when you’re 14 years old? I would think so. In one study from the Warren and Campbell paper, participants saw ads asking them to follow or break a dress code. Some learned that the code existed to honor a dictator. Others were told it honored war veterans. Although both groups considered breaking from the dress code a sign of autonomy, it only seemed “cool” to be autonomous in the former example, when they were breaking from a norm that was clearly absurd.

Where this definition of cool—iconoclastic, legitimate, and bounded—runs into trouble for me is the concept of success. Some people who break rules but don’t achieve success are seen as losers or failures. For others in the business world—Bill Gates, Warren Buffett, Mark Zuckerberg—it’s precisely their thrilling success more than their “bounded” “autonomy” that’s the real source of their coolness. They accomplished something. Warren and Campbell could argue that the real source of these CEOs’ cool factor is that they confront pre-existing norms. But every business confronts norms: You’re either creating market share or you’re stealing it. Autonomy is cool. But so is power and money, even when it creates or supports norms that iconoclasts want to destroy.

One of the most interesting implications of this research is what it means for marketing—particularly when trying to persuade young people who are more caught up in the race to be cool. For example, rather than browbeat teenage consumers with earnest pleas to not smoke or drive drunk, the paper recommends aligning negative behavior with a loser mainstream. In fact, that was the thesis behind The Truth’s famous campaign against smoking: Associate teenage smoking with an idiot conformity. In 2010, the American Journal of Public Health published a study which concluded that these ads significantly reduced teen smoking around the turn of the century. Now that’s pretty cool.

This post originally appeared at The Atlantic. More from our sister site: