Italy—yes, Italy—is now an example for European leaders to admire

European voters are angry. They are angry with the mainstream political parties, and in many countries delivered a stinging rebuke to the established order in the elections for the European Parliament. They are angry at years of austerity and low (or negative) growth, and voted in large numbers for fringe parties that say the EU is to blame.

European voters are angry. They are angry with the mainstream political parties, and in many countries delivered a stinging rebuke to the established order in the elections for the European Parliament. They are angry at years of austerity and low (or negative) growth, and voted in large numbers for fringe parties that say the EU is to blame.

Except, that is, in Italy.

The center-left Democratic Party of prime minister Matteo Renzi (pictured above) cruised to victory in this weekend’s poll, with nearly twice the share of its nearest rival, the upstart anti-austerity Five Star Movement. Although Italian GDP has fallen in 10 of the past 11 quarters, voters seem to think that the center-left party led by the energetic 39-year-old prime minister is their best bet to shake Italy out of its long malaise.

Consumer confidence data out today provides another fillip for Renzi’s cause, with the headline index touching a four-and-a-half year high in May:

Buoyed by the upturn in consumer confidence and, especially, his party’s election victory, Renzi says he now has a clear mandate to push his “pro-growth agenda” (is there ever any other kind?). “I consider this a vote of extraordinary hope,” Renzi said at a press conference yesterday.

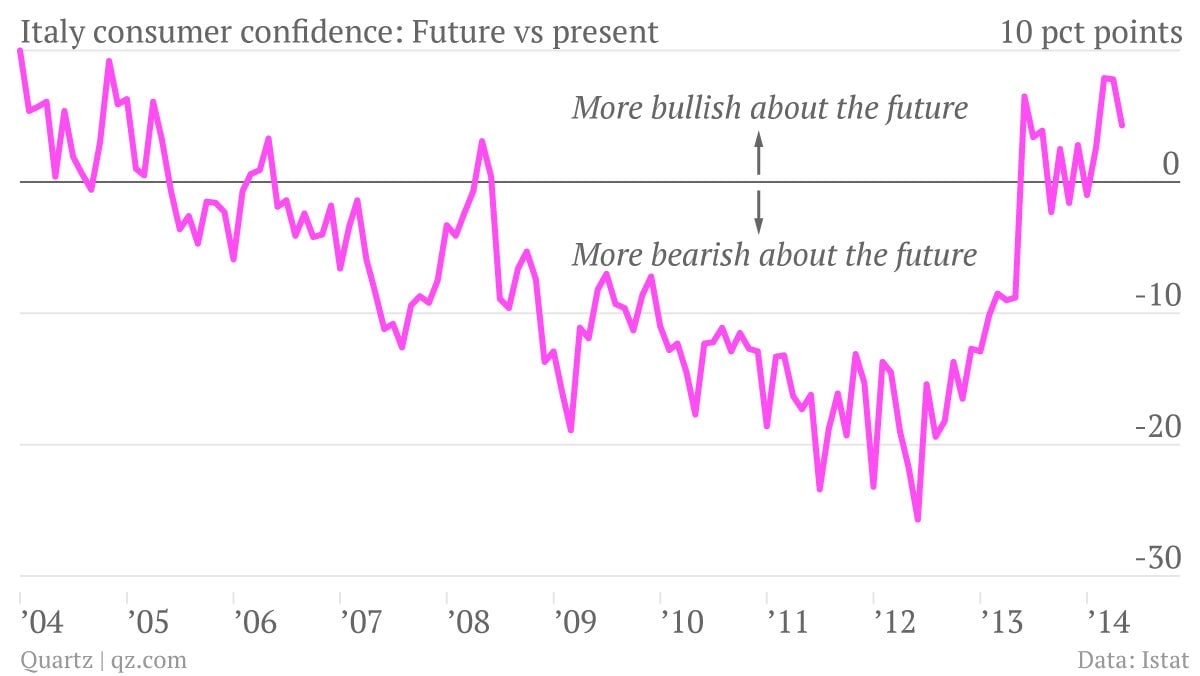

That hope is illustrated by recent data, with the sub-index for Italian consumers’ confidence in the future consistently surpassing their assessment of the present for the first time in a long time:

As we have written before, in some stronger economies—namely, in Germany—the opposite is true: Businesses and individuals are fearful of the future despite being content with the present. In Italy, the rise in future optimism may simply reflect the fact that things can’t get much worse—any promise of change to the country’s toxic mixture of a sclerotic economy and a chronically unstable political system is welcome.

And although ordinary Italians have the most at stake, other European leaders will also look to Renzi to prove that established, centrist parties can address voters’ gripes better than the euroskeptic upstarts on the far right and left. But Italy’s long history of false starts makes this quite a gamble. Until there is more tangible evidence of durable reforms, the risk is that the recent rise in optimism will fizzle like so many before it in Rome—yet another example of the triumph of hope over experience.