In a very online world tech platforms are quickly emerging as a creative new way to send help directly to Ukrainians.

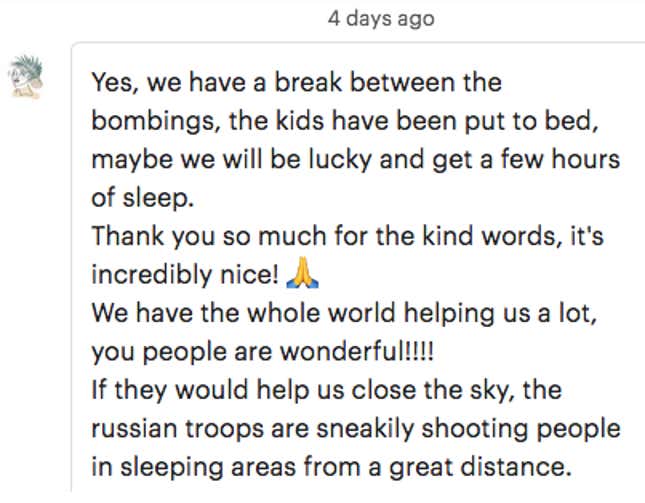

Yes, people are coming up with novel ways to send money, counter disinformation, and transport refugees. But perhaps more importantly, these platforms provide a sense of connection, a way to virtually travel into a war zone and talk to a person in need of help. Donating in this manner puts a face to the conflict in a way that writing a check to Red Cross just can’t.

According to a March 4 tweet from Airbnb’s CEO Brian Chesky, more than 61,000 nights were booked in Ukraine on the platform over the course of 48 hours, with total gross booking value at nearly $2 million. Users are reserving stays and then letting hosts know that they don’t intend to use them, they just want to send a donation. The short-term rental company said it has turned off guest and host fees in Ukraine, for now.

On Etsy, users are buying digital stickers from Ukrainian shops as a way to funnel money to Ukrainians. People are also turning to ride-sharing apps such as BlaBlaCar to help transport refugees. Last week, BlaBlaCar’s CEO tweeted that 50,000 people have been transported either across Ukraine or to neighboring countries like Poland, Romania, and Hungary. People have also been pushing back against Russian state media, and creating space for free speech by turning Google Maps listings and other user-generated review sites for Russian businesses into a place to comment on the Russia-Ukraine crisis.

These platforms provide “hidden infrastructure [that] can be turned on where necessary in response to an unexpected event,” said Arun Sundararajan, a professor at New York University’s Stern School of Business whose research focuses on the sharing economy.

Why Airbnb instead of the Red Cross or another established charity?

One of the reasons that people who want to help Ukraine are turning to Airbnb and other online marketplaces is because they offer transparency around who’s sending money and who’s receiving it. “People are much more motivated when they know who is getting the money that they’re getting all of it,” said Sundararajan.

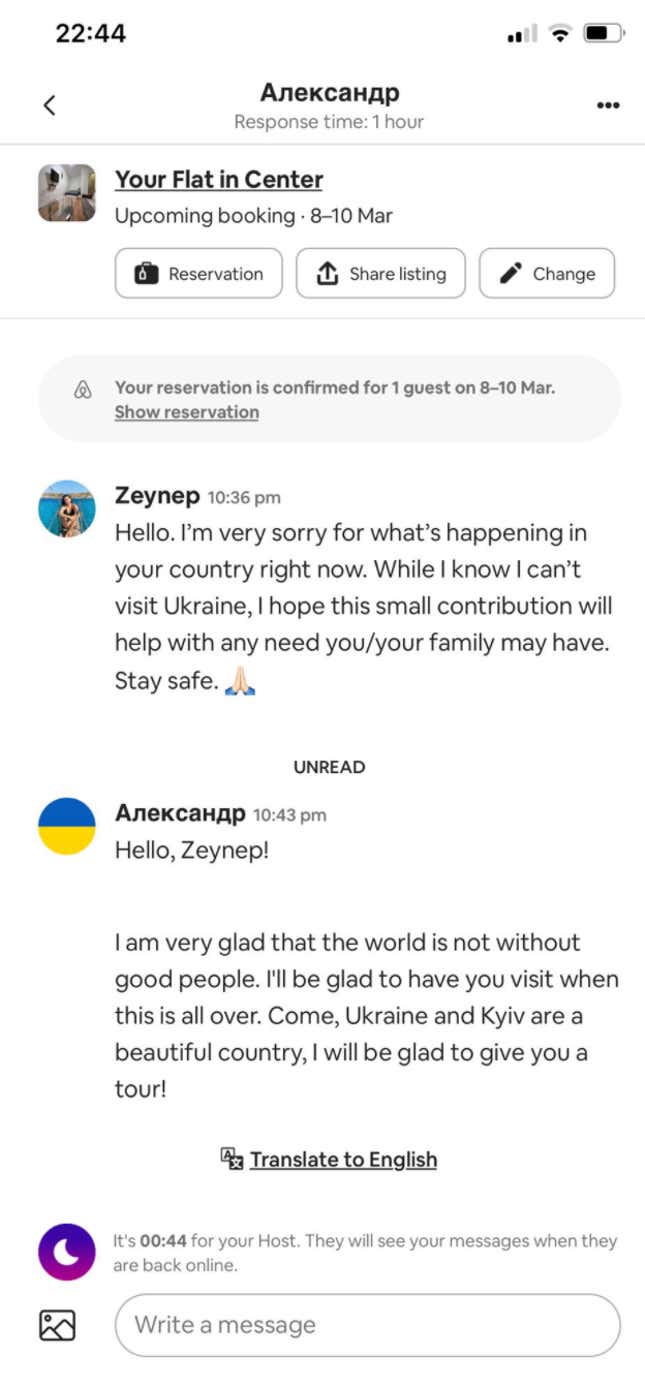

After seeing the buzz surrounding Airbnb donations on social media, Zeynep Gozen, a marketer in London, decided to join in. “These are the hidden figures behind the war, and they’re actually suffering as well financially,” said Gozen, 34. “We all contributed like the big sort of the big charities and donations, but I want to go after the little ones as well because I know just how much it impacts them.”

She paid for two nights, about £50 ($66), in Kyiv. Originally from Turkey, Gozen said she was moved in part by having seen the effect of war on Syrian refugees.

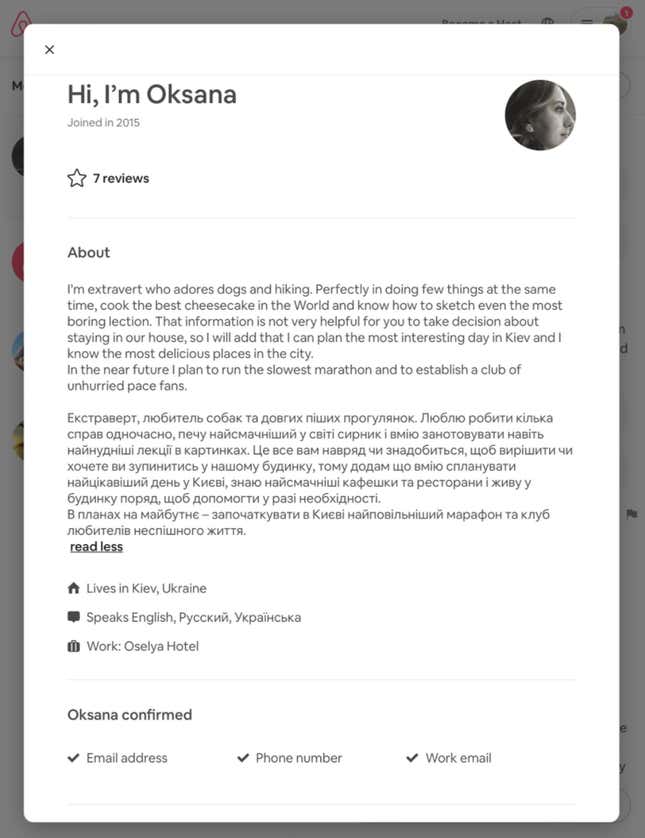

Joni Novotnak, a 64-year-old retired teacher who lives in Pennsylvania, said she searched for a “regular person or family running a home,” in the capital Kyiv, wanting to give to an individual, rather than a corporation. “Once I got a response, I thought I would continue to check in on that person,” she said. She paid for two nights in Kyiv, which totaled $120. Similarly, Gozen said she chose to “stay” in Kyiv because she hopes to visit it one day.

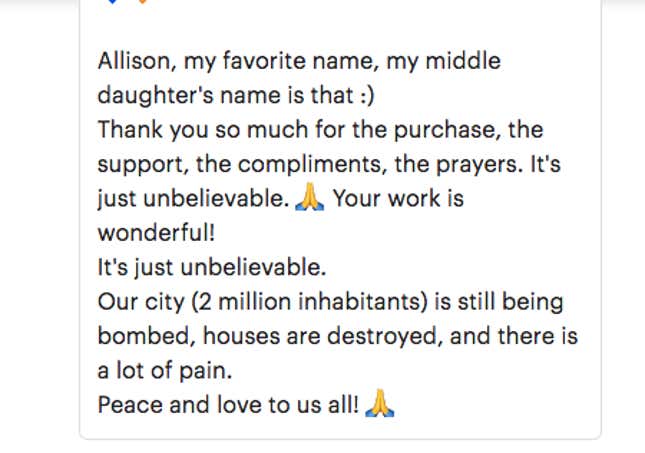

A visual of someone’s face or home makes the transaction more personal, said Regina Tuma, a professor who focuses on media psychology at Fielding Graduate University. “[It’s] a way of personalizing your money,” said Tuma. “It makes you feel like I’m just not donating somewhere…I’m actually helping someone in Ukraine.”

Yes, there will be bad actors

It’s possible to manipulate these platforms. There have been social media reports of BlaBlaCar drivers in Kyiv deceiving passengers and asking for prepayment and then canceling the ride after receiving the money. And it would be easy to pretend to be a Ukrainian resident on some online marketplaces. When there’s a change to the system, there’s always a risk of bad actors taking advantage of it, said Sundararajan.

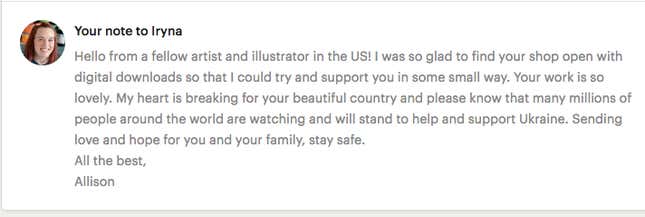

The Etsy and Airbnb users Quartz talked with were aware of the risk. “In the back of your mind the whole time, you’re like, I’m 98% sure I’m not getting catfished, but you never know,” said Allison Glancey, a 52-year-old illustrator and Etsy seller.

People who are online enough to want to use a tech platform as a way to donate directly though, are savvy. Glancey said that she checked to see that sellers had lots of prior sales before buying $35 worth of digital stickers from two Ukrainian-based shop owners. Novotnak said she scanned the comments on Airbnb to get a feel about the person and place before she booked.

Trusting Airbnb, Etsy, or another online community as much—or more than—an organization like Red Cross or Unicef “speaks to a broader change in our reliance on platforms versus governments and other nongovernmental organizations during times of crisis,” argues Sundararajan. For instance, for many, Yelp reviews carry more weight than a city’s sanitary grading of a restaurant, he said. This year, a global survey from Edelman Trust Barometer showed people trust technology more than any other industry “to do what is right.”

These platforms have flourished by building trust and promising a human connection, whether that’s a handknit hat or staying in someone’s home, and repurposing them to donate directly to Ukrainians builds on that sense of community. “I’m trying to reach out wherever I can because I feel so helpless,” Novotnak said. “Little things like this I think can help.”