India’s new government is widely expected to ease restrictions on foreign investment and open up several sectors. But international competition won’t be increasing in multi-brand retail, or supermarkets that sell a variety of products and brands. The rationale, as new commerce and industry minister Nirmala Sitharaman said yesterday, is that farmers and small traders might be affected if you “open the floodgates of multi-brand retail”.

A number of large Indian companies already operate such stores. And they are losing money trying to get Indians to buy food and groceries, the largest component of the retail pie, from modern outlets rather than the ubiquitous corner shops and carts that stock up to meet seasonal demand and local tastes.

India’s top ten modern food retailers reported accumulated losses of Rs13,000 crore ($2.2 billion) during the 2013-14 fiscal, ratings firm Crisil has estimated in a report. While revenues in the sector have ballooned from Rs3,000 crore ($500 million) in 2008 to Rs23,500 crore ($4.05 billion) now, losses have kept pace.

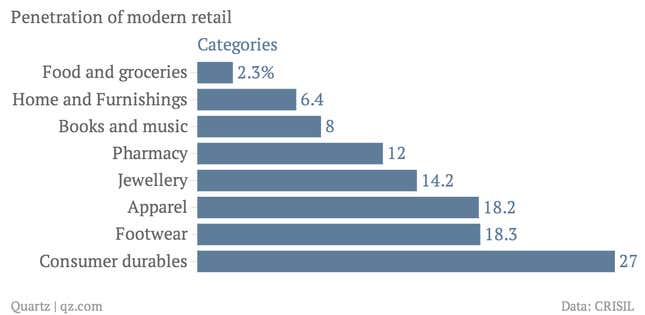

The bad news for modern retailers is that food accounts for the most revenue and is the product category that drives walk-ins to retail stores. Nearly 70% of India’s retail trade, estimated to be a $500 billion business, is food. And that is the segment that modern retail has been least successful in penetrating, with a low 2.3% presence.

For global retailers such as Walmart and Tesco, food and groceries account for more than 50% of revenues. While the segment typically has low margins, it is attractive globally because it is largely insulated from the pressures of e-commerce. Global and chain retail accounts for a little over five percent of the overall retail market, according to industry chamber Ficci.

Crisil studied India’s top ten food retailers, including Best Price Modern Wholesale stores, Metro Cash & Carry India, Aditya Birla Retail, Bharti Retail Ltd, Reliance Fresh Ltd, and Trent Hypermarket Ltd. Best Price is operated by Walmart’s India unit, while Metro Cash and Carry is operated by the Indian arm of Germany’s Metro AG. The others are subsidiaries of large Indian conglomerates.

Crisil forecasts that things are going to get worse before they begin to get better for the big operators. Losses will peak in 2017, at Rs17,000 crore. But with government policy being what it is, there is little hope for buyouts or consolidation, or new international players. Instead, firms will have to spend more in order to achieve efficiency and scale.

If India’s modern retailers are finding it so hard to wean customers away from the so-called kirana stores, perhaps the government worries too much about keeping the “floodgates” down.