It has become relatively common, even unremarkable, for young people to spend a time after they’ve graduated college waiting tables, doing clerical work, or working retail. Nearly half of a group of four-year-degree graduates surveyed by McKinsey last year said they had a job that didn’t require a degree. And many are advised to take any job they can find, even if it’s one that doesn’t require a degree, to build their resumes and skills.

But new graduates might want to reconsider such employment, according to a new NBER working paper. Those early years being over-educated for a job can have lasting negative consequences in a person’s career trajectory. Many that have the intention of spending only a short time in a job where they’re much more educated than their co-workers have a hard time taking that next step or catching up later on.

Previous studies have estimated that as many as a third of American workers are over-educated for the jobs they hold. The researchers, from Duke and the University of North Carolina, find substantial negative effects on both current and future wages for these workers, as well as on their ability to move on to a better-matched job later on.

Being over-educated for a job is better than not having one at all, but the researchers found that the “scarring effects” of over-education on future wages are similar in a lot of ways to the after-effects of prolonged unemployment for those re-entering the workplace.

The paper looks at data from the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, which followed the careers of a group of 6,111 for up to 12 years, depending on their age when the survey started. The job market has changed a lot since the 1980s. For one thing, it has gotten much easier to search for and find a job, with services such as LinkedIn. But if these effects were all about challenge of job-hunting, the effect would be concentrated in the early career, and vanish quickly. That’s not the case, which suggests there’s something more fundamental going on.

The results remain relevant to many who graduated in recent years (paywall) and are finding themselves without employment in their chosen fields after college. Even though the economy appears to be getting better for this season’s grads, the effects of the financial crisis will be felt for years.

The new study found that 66% of over-educated workers remained in employment they were over-educated for a year after their first job. Past experience working as in such a job leads to a wage penalty of between 2.6% and 4.2% that lasts for years. While many manage to catch up relatively quickly, the problem of over-education for one’s job was extremely persistent for about 30% of the sample the study looked at.

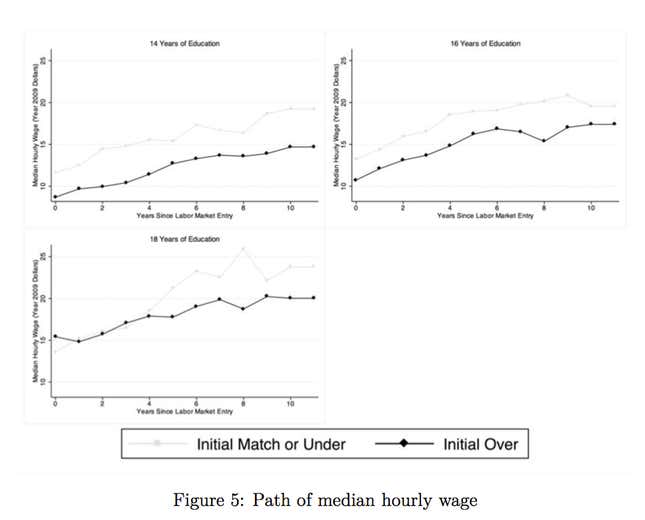

At all levels of education, from those with a two-year college degree (14 years of education) to those who have gone to graduate school (18 years), the wage gap was significant and could persist even a decade after entering the labor market. The negative wage effects persisted even when cognitive ability was controlled for:

Women were 5% to 13% more likely to be over-educated for their jobs. That could be because they are more likely to value jobs that offer flexibility, but it could also be a sign of employee discrimination. Regardless, the authors write, over-education plays an important and usually unexplored part of the gender wage gap.

It’s easy to be flip about young people needing time to figure out what they want to do, and it may well be true that retail jobs teach important lessons about hard work and management. But the cost of higher education, the increasingly large debt load that students are taking on, and these long-term career effects make it clear that early choices can lead to persistent problems—and that many graduates need support as they enter the job market.