The European Central Bank may finally have the political cover it needs to act

A mixed bag of data came in from Europe this morning:

A mixed bag of data came in from Europe this morning:

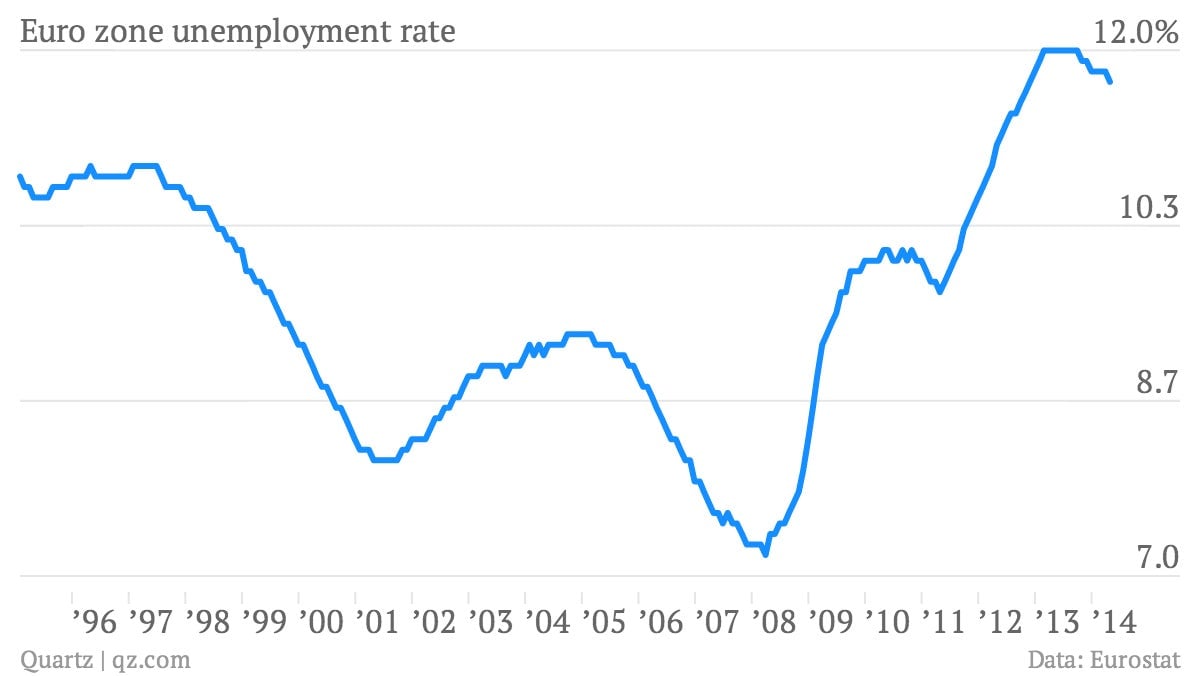

The euro zone unemployment rate ticked down to 11.7%. That’s the lowest since the autumn of 2012. But it’s still ridiculously high by historical standards.

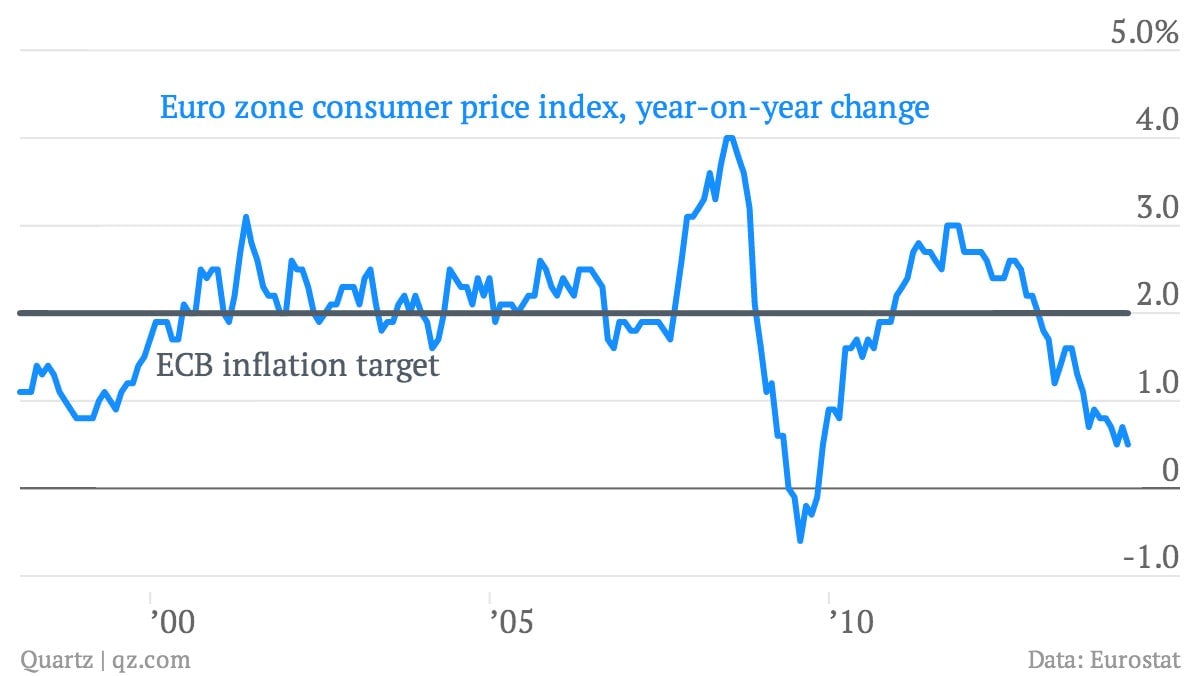

The real data point du jour, however, is Europe’s inflation, as the continent continues to flirt with deflation. Prices grew a meager 0.5% in May, compared to 0.7% in April.

This is a central banker’s worst nightmare. These financial technocrats know that they can snuff out inflation by raising interest rates (thereby inducing a painful slowdown in the economy). But there’s no clear prescription for dealing with deflation—a persistent, broad-based down-drift in prices. And while falling prices might sound good to consumers, deflation acts as an albatross around the neck of an economy, as consumers put off spending in the expectation of price declines.

But there is an upside to Europe’s weakening price pressures. They’ve quieted criticism from the hawkish wing of the bank—those more worried about high inflation than high unemployment—and opened the door for the ECB to do more to help the European economy get back on its feet.

That’s why expectations are so high for the ECB to announce some sort of new action at its meeting on Thursday. But if recent history is any guide, high expectations are a dangerous thing when it comes to ECB action.