Meta’s president of global affairs, Nick Clegg, recently posted a nearly 8,000-word manifesto outlining his vision for the future of the metaverse. It may seem odd that Clegg, a career politician who previously served as the deputy prime minister of the UK, would post such a long and detailed treatise on a technology not central to most of his life’s work.

But in recent years, Clegg has moved into the spotlight as Meta’s public policy framer and, sometimes, defender. If Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s metaverse vision is mostly resonant with tech insiders and Wall Street, Clegg’s may serve as a more direct and clear entreaty to those in the public sector to take Meta’s new mission seriously.

However, because many interested in Meta’s perspective on the metaverse and its challenges likely won’t take the time to read the lengthy document, it’s worth surfacing the central theme highlighted by its author—protecting the overall safety of the user. “The rules and safety features of the metaverse…will not be identical to the ones currently in place for social media,” writes Clegg. “Nor should they be.”

Using the real world to understand the metaverse is a start, but not an answer

Curtailing harassment and protecting children from bad actors online has become one of the emerging concerns around the virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality immersive platforms that comprise the metaverse. Current game ratings, as well as abuse reporting systems in place for console games, have generally helped to keep 2D video gaming viable as a growing entertainment platform.

But as the metaverse, or, more specifically, the immersive internet, becomes mainstream, the nature of the interactions in these virtual spaces will require new approaches toward guarding the mental and emotional health of its users.

To outline his vision of how companies might handle public safety in the metaverse, Clegg offers a perspective that hews more toward how we interact in real life. “In many ways, user experiences in the metaverse will be more akin to physical reality than the two-dimensional internet,” writes Clegg.

“For example, in the US, we wouldn’t hold a bar manager responsible for real-time speech moderation in their bar… but the bar manager would be held accountable if they served alcohol to people who are under-age. We would expect them to use their discretion to exclude disruptive customers who don’t respond to reasonable warnings about their behavior.”

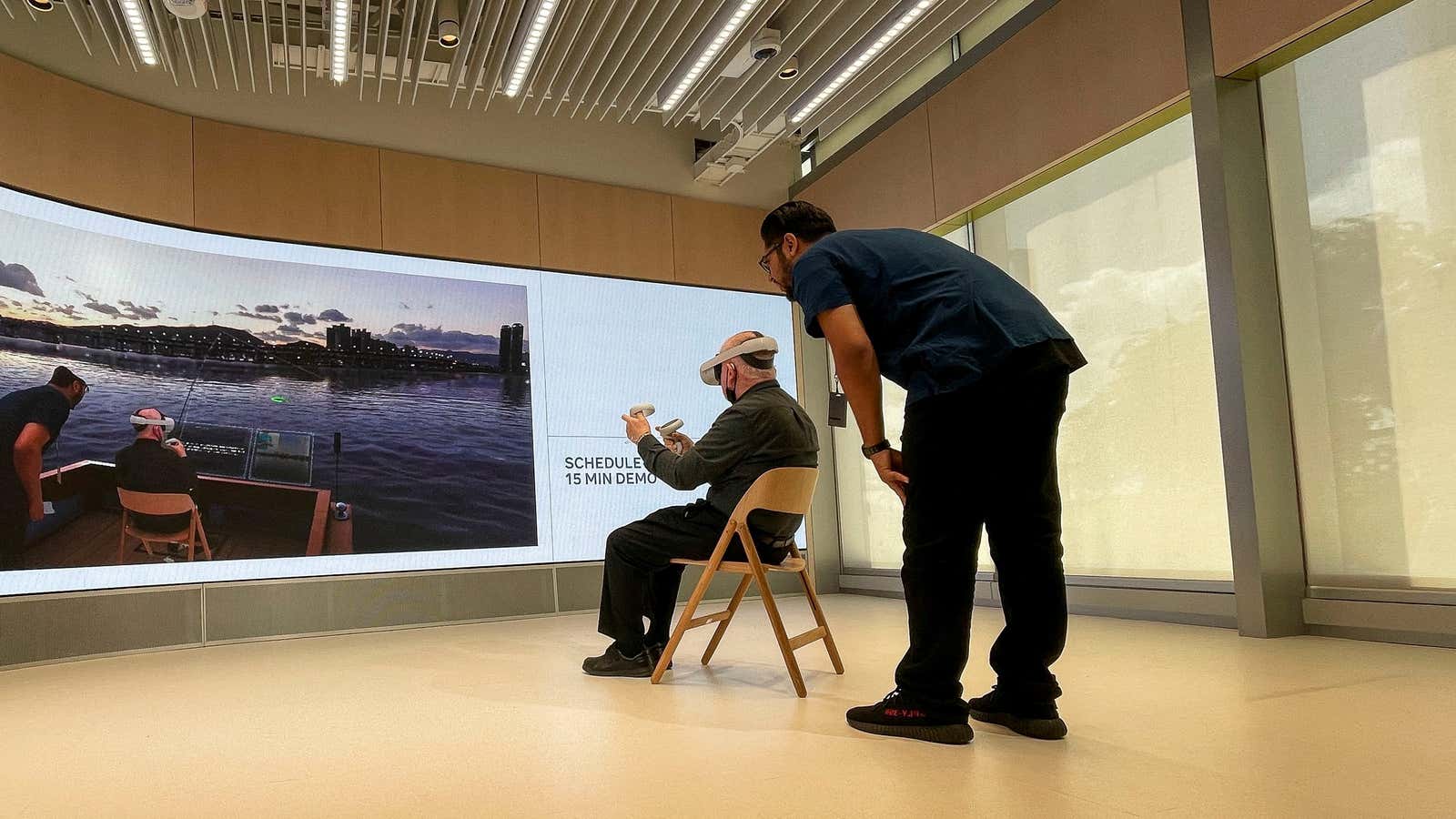

To that end, Clegg references Horizon Worlds, Meta’s new VR social network, which could eventually become the successor to Facebook, if Zuckerberg’s vision takes hold.

The limits of control in social media will become more challenging in the metaverse

On Horizon Worlds, Meta has devised an elaborate but very user-friendly system for reporting and guarding against bad behavior. According to the app’s safety guidelines, it records “recent audio and other interactions” that may be used to help report and address “harmful conduct.”

“We would expect customers who were upset by aggressive or inappropriate speech to be able to speak to the manager about it, and for some kind of action to result,” writes Clegg of the bar-to-metaverse analogy on Horizon Worlds. If this dynamic works, it could help inform the safety practices of other emerging metaverse platforms.

Even so, the problem with Clegg’s example is that it is pointed at the wrong product. Throughout his essay, Clegg frequently speaks in future-tense about what the metaverse “will be,” but largely fails to account for what is happening right now in the foundational realms of the immersive internet. Currently, the largest growth segment in VR is in gaming, not immersive versions of social media Horizon Worlds or its competitors like Microsoft’s AltspaceVR. In many VR gaming spaces there is a social component where people meet, chat, share their lives, and go on to form offline friendships.

And while Meta says that Horizon Worlds, a free app, has 300,000 users, the real social media acton in VR on Meta’s servers seems to be happening on games like Meta’s Population One.

Good intentions won’t save immersive internet users, but realistic approaches might

Meta bought Big Box VR, the studio behind Population One, nearly a year ago. In short, the game is nearly everything Fortnite and Call of Duty gamers have come to love about those console-based battle royale games, but in VR. That includes the social aspects of those games.

When asked by Quartz how many users the game has, neither Meta nor Big Box VR offered a figure, but the $30 game, which also has in-app purchases for skins and various weapons, remains one of the top selling games in the Meta Quest app store, alongside apps like Beat Saber (also owned by Meta), Resident Evil 4, and The Walking Dead: Saints & Sinners.

As a frequent user, I can attest that Population One is usually a friendly space for gamers. Still, I have witnessed harassment and even been subjected to it (thankfully only a couple of times since its launch in 2020). One recent incident became so troublesome that I decided to report the behavior—the first time I’d ever taken such an action in a gaming space. The in-app reporting tools didn’t seem to yield results, as I continued to be placed in games with the gamer in question.

So I took things to the next level and wrote to the email address listed deep within Big Box VR’s website. The first two times, my email was bounced back with a message indicating that I had already been helped, despite no contact from a support person. It took a third email to finally get a real person to respond to my report. Since then, I haven’t seen the gamer once, and the game is as enjoyable as ever.

Nevertheless, given my anecdotal experience, it appears that the safety measures Clegg touts in his essay may not be in place on Population One, easily the most social VR experience that I, along with many other Quest users engage in on a regular basis. Both Horizon Worlds and Population One are Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) rated as for Teens (users 13 years-old and up), but the personal safety controls on the former are far more detailed and responsive than the latter.

If Meta plans to avoid the missteps that have plagued Facebook in the past, rather than promoting the guardrail virtues of its nascent social VR platform, addressing the safety of users in its present-day VR gaming platform is probably just as, if not more important.