Prices are rising. But why?

The pandemic. Government measures to fight the pandemic. The US Federal Reserve. Base effects. Supply chains. A dearth of investment. Corporate greed. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. A labor shortage. A wage shortage. ESG investors?

Ok, there are a lot of answers. The challenge is that many of them are right, to some degree. But to shut off inflation without shutting down the economy, policymakers at central banks and national governments need to push against the right problems.

At the Fed, hundreds of economists work to provide analysis of economic conditions. They can spend months or years on research for peer-reviewed journals, but they also generate working papers and analyses that attempt to provide clarity to policymakers and the public at a faster pace. This kind of real-time applied social science isn’t easy.

Two economic letters from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (FRBSF) are an example of how tricky it can be to understand how decisions made by governments, companies, and individuals change the economy. One, published in October 2021, provided an early estimate of how federal stimulus would affect inflation, while a second, published this March, tackled the same question with a different approach.

The first paper relied on history and found a small impact; the second looked at the state of the world and found a large one. The authors agreed to talk through their work with me in a May interview to help understand our unprecedented economic situation.

Will

the American Rescue Plan tip the US into inflation?

In March 2021, Democrats in Congress enacted the final piece of legislation designed to cushion Americans from the pandemic, the American Rescue Plan. There were concerns that the $1.9 trillion bill was too large for the need, following $3.1 trillion in federal relief enacted in 2021. After its passage, Harvard’s Larry Summers warned there was a two in three chance it would lead to high inflation or a crash caused by the Fed’s efforts to fight it.

When the bill was passed, researchers at the San Francisco Fed followed this debate with interest, and began thinking about how to examine it rigorously. One group decided to try to forecast its impact based on how fiscal stimulus affected employment and inflation in the past.

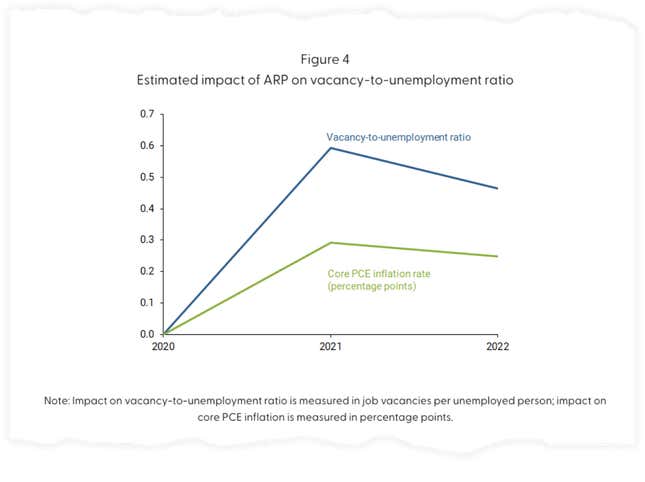

They looked at a measure of the labor market, the ratio between vacant jobs and unemployment: A high ratio, with tons of open jobs and low unemployment, would show a very tight labor market, while the opposite, with few open jobs and high unemployment, would show a very loose one. By comparing the historical effect of fiscal stimulus on that ratio, the economists could get an idea of how this round of government spending would affect the labor market, and inflation.

In their note, released in October 2021, the authors forecast that the labor market would tighten considerably, to match its peak in 1968. But they expected this would only add 0.3 percentage points to inflation through 2022, as measured by the government’s tracking of personal consumption expenditures (PCE).

In the seven months between the passage of the bill and the release of their paper, PCE inflation increased by 2.6 percentage points; today, PCE inflation is up 6.3% over the previous year. Adam Shapiro, a vice president in the bank’s research department, says the forecast of a tightening labor market turned out to be accurate. The historical correlation between the labor market and inflation, however, didn’t hold.

One way to interpret the result is that most of this inflation actually came from other sources—spending prior to ARP, supply-chain hiccups, the pandemic-driven imbalance between spending on goods and services. Or, it means that something unusual is happening the economy that affects the relationship between hiring and price increases.

Regis Barnichon, another author of the paper, says this might be evidence of unprecedented government spending during the pandemic: If the labor market and inflation historically react in a predictable way to a certain amount of spending, exceeding that normal range could lead to unexpected results.

“The CARES act and the American Rescue Plan were, by any historical standard, extraordinary in their size,” Òscar Jordà, another San Francisco Fed economist, says. “There’s never been a package that big in the entire post-World War II history.”

Did

the American Rescue Plan tip the US into inflation?

Jordà and other economists at the bank took a different approach to the question of how the ARP and other fiscal stimulus affected price levels. They looked at actual data about the US economy during 2021 and compared it to statistics from other advanced economies in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Fernanda Nechio, a vice president in the SF Fed’s research department, says that a long historical sample offers more precision, but examining real-time data can shed more light on the specifics of an extreme situation.

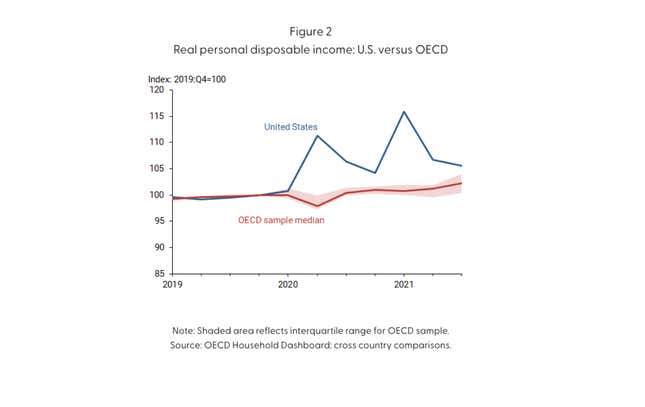

The researchers started by looking at changes in disposable income in different countries as a proxy for the variety of stimulus packages introduced by different governments. By this measure, the generosity of US government relief far exceeds the median member of the OECD, just as American inflation outstripped that benchmark.

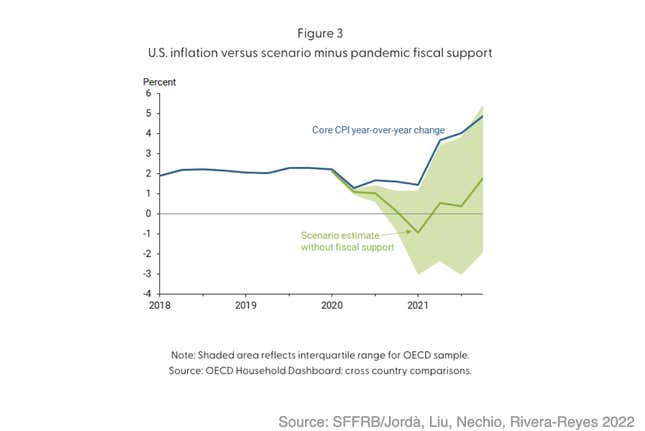

Next, the researchers constructed a model to test if the different government responses could be linked to inflation. Their analysis, published in March, estimated that US stimulus added 3 percentage points to inflation in 2021, as measured by changes of core inflation measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI). That’s a significantly larger effect than the first paper’s estimate, even in two different indices.

But it’s also very uncertain, as shown by the green shading in this chart comparing actual inflation to a scenario where the US didn’t provide fiscal support. In that case, the economists fear the US might have tipped into outright deflation.

This uncertainty, even in an after-the-fact analysis, shows the bind the US government faced when it enacted the ARP and its two predecessors in 2021. At the time of the votes, inflation was low—the year-over-year CPI reading in February 2021 was 1.6%—death rates were high, and vaccines were unavailable. Weighing the risks of higher inflation against joblessness and deprivation feels different in that environment.

“To an unemployed person, inflation is infinite,” Jordà says. “If you’re not employed, you don’t have income to buy goods. It doesn’t matter what the price is.”

How we understand inflation

What can we learn from assessing these two papers together?

For one, they help clarify the push and pull of inflation dynamics. Too much demand is the straight-forward explanation of price increases: Too many purchasers bidding up a scarce good, whether that’s furniture from China or restaurant workers. But inflation can also come from supply problems: If there isn’t enough oil on the market, its price will rise, or if there aren’t enough workers where the jobs are, wages will increase.

The debate over recent price increases and when they will subsist could be characterized as one between excess demand (the ARP was too big!) and crimped supply (consumers spent more on goods, clogging supply chains!). It’s very difficult to disentangle one cause from the other. Did too much consumer spending overwhelm factories and distributors? Or did the pandemic increase friction so much that prices would have risen, even with moderate stimulus?

“If you have a fiscal package that’s happening at the same time as a large supply constraint, it might have a much larger effect than anything you’ve estimated in the past,” Shapiro says. “[The second paper’s] methodology inherently accounts for that, because they’re looking at just the period where a supply constraint is happening across the whole world.”

Now, though, we see the effects of that fiscal stimulus falling away—only to be replaced by a different set of challenges, headlined by rising food and energy prices linked to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The Federal Reserve has begun a hiking cycle to fight inflation, and financial conditions are tightening. As the US government works in concert to pull demand out of the economy, some observers fear that it may overcorrect the wrong way.

So, is there a path to beating inflation without beating down the economy?

“The answer to your question is going to be how policymakers filter out the different factors that are moving inflation,” Jordà says. “There is a path to soft land, but there’s going to be a lot of noisy signals. So it’s going to be especially difficult to do it, but not impossible.”