Pakistan gets most of its electricity from power plants run on imported natural gas, the price of which has soared in the last few months as Europe scrambles to buy its own supply from anywhere but Russia. Pakistan also imports nearly all of its crude oil for vehicles and other uses, which is at its highest cost in a decade. As a result, the country’s spending on energy imports over the last 10 months has doubled.

On June 8, the government announced a partial solution: Less work for public employees.

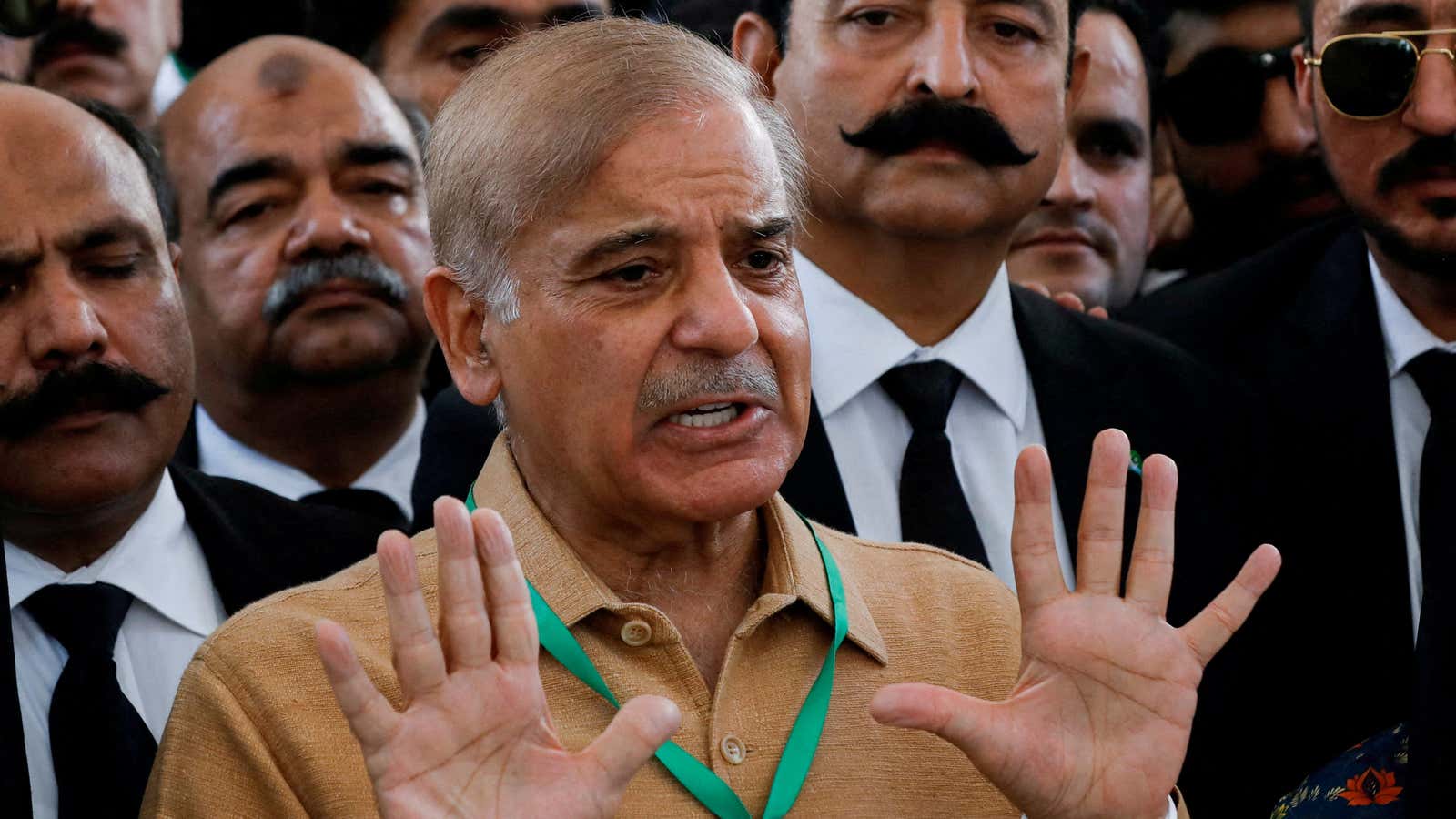

After his election in April 2022, prime minister Shehbaz Sharif implemented a six-day work week for public-sector workers. That will now be cut back to five, and the government is considering a mandate that employees work from home on Fridays. Other energy-saving measures include the end of free meals for some officials and the periodic shutdown of some streetlights.

Venezuela temporarily adopted a similar cut during an energy crisis in 2016, and the idea has been floated by energy executives over the last year in the UK, which also relies heavily on natural gas imports. The move may have the added benefit of lowering Pakistan’s carbon footprint.

World leaders have few options to control energy prices

Pakistan’s strategy underscores a key challenge of the global energy crisis: There’s not very much that political leaders can do to quickly increase the supply of oil and gas on the market. US president Joe Biden said last week that he will visit Saudi Arabia to urge it to pump more oil, but it’s not clear that the country will be willing to, or even that it’s capable of pumping enough to offset the loss of Russian oil on the global market. Increasing global trade of natural gas is even trickier, because doing so would require the construction of new multibillion-dollar liquified natural gas terminals that take three to five years to build. By the time a terminal is built, demand may have changed again.

The fastest solution to high energy prices is to find creative ways to chip away at demand. That could turn the crisis into an opportunity, if it speeds the adoption of efficiency innovations that smooth the long-term transition away from fossil fuels.