Today marks the 70th anniversary of D-Day, among the most pivotal moments of the most pivotal event of the 20th century. The beach landing at Normandy may not have had a direct impact on the nature of US cities, except insofar as no American life was the same that day forth. But in the spirit of looking back on that era we turn our attention to something with very clear relevance to the character of our metro areas: the Autobahn.

Germany’s impressive road network partly inspired the Interstate Highway System that changed the shape of American cities (for better and worse). It also might have hastened Hitler’s rise to power.

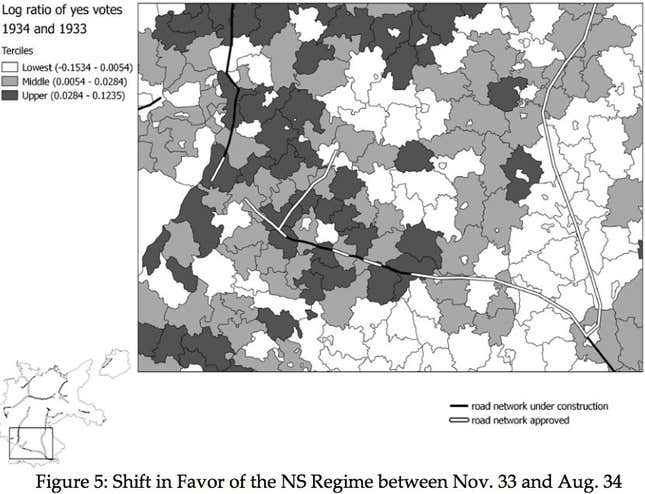

That’s the conclusion reached by economists Nico Voigtlaender of UCLA and Hans-Joachim Voth of University of Zurich in a fascinating new working paper on the Autobahn’s role in the Nazi regime. By analyzing voting records between November 1933 and August 1934 alongside highway patterns, Voigtlaender and Voth found that any opposition to Hitler swung in his favor significantly faster in areas where the Autobahn was being built than elsewhere. With the country still recovering from the Great Depression, Germans might have seen the new roads as a sign the Hitler regime could jumpstart the economy.

“We find strong evidence for changes in voting behavior in one of the most salient examples of infrastructure spending,” Voigtlaender tells CityLab. “Also, we show this in a context of attracting votes from the opposition—i.e., people who were hardest to convince.”

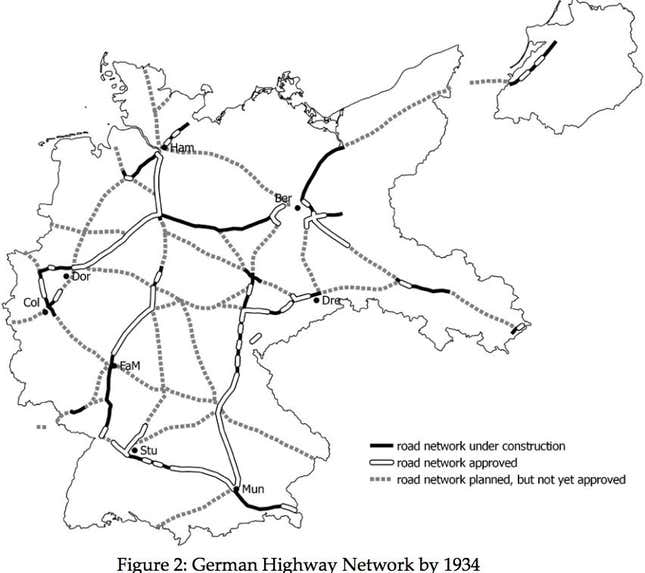

As Hitler rose to power in 1933, he wanted to show that his government could get things done in a way the Weimar government had not. Building the Autobahn was the perfect demonstration. Hitler himself broke ground on the highway system in September 1933—telling the crowd to “get to work”—and within a year construction was underway in 11 major corridors. The propaganda that followed referred to “roads of the Führer” as a way of connecting highway completion with an effective Nazi regime.

Voigtlaender and Voth studied the effect of this infrastructure program by looking at results from two votes around this time: a parliamentary election in November 1933, and a referendum to make Hitler supreme leader in August 1934. Neither election was a free one. Storm troopers loomed over polling stations and coerced voters. But opposition did still exist. More than a quarter of Hamburg and Berlin voters rejected Nazi candidates in the ’33 election, and nearly a quarter of Aachen voters cast “no” at the ’34 ballot.

Pairing voting records for 901 counties with the geography of the emerging road network revealed clear disparities in pro-Nazi voting shifts during this 9-month stretch. While votes against the regime declined by 1.6% on average, opposition votes declined by 2.4% in precincts near Autobahn construction. Put another way, those living near a new highway were quicker to acquiesce to Nazi rule.

The map below shows that areas where the road was being built (black lines) tended to align with bigger swings in “yes” voting (the darker the district, the bigger the swing in Nazi approval):

As a further check on their conclusions, Voigtlaender and Voth went back to the elections of March 1933, the last semi-free elections of the era. Votes against the Nazis in that election were “nearly identical” in the two focus areas (53.8 to 53.3% with and without construction). But between then and August 1934, Nazi opposition fell by 15% in areas outside the Autobahn’s developing footprint, and fell by 25% in areas within it.

Voigtlaender and Voth conclude:

“We find that electoral opposition to the nascent dictatorship declined significantly in districts traversed by the Autobahn. This effect is much bigger after November 1933 than before, in line with spending patterns over time. There is a clear gradient to the collapse in opposition — the further away from the highways a district was, the smaller the reduction in opposition.”

The link is pretty convincing (the researchers even argue, based on additional tests, that it’s “probably” causal). It’s not hard to imagine how things might have unfolded. Road workers spent money at local shops, generating optimism in both the economy and the new government. At a wider scale, the regime showcased the Autobahn as a sign of its ability to guide Germany back toward global prominence.

Interestingly, write the researchers, that favorable impression was largely an illusion. The Autobahn failed to stimulate as much employment as it promised; instead of putting 600,000 Germans to work, it employed just 125,000 at its peak. Car ownership was also very low in the early 1930s, limiting any immediate benefits of living near a road. In all likelihood, economic recovery was on its way with or without the project.

“Germans often believe that highway construction was the only bright spot of the Nazi regime,” says Voigtlaender. “Our interpretation is that this is based on a misinterpretation of the Autobahn’s true economic effect.”

While the Autobahn might have helped Hitler consolidate power more quickly, his eventual claim on that power was inevitable even at the time. The same couldn’t always be said for Allied victory in Europe. Though after D-Day things certainly looked brighter.

This post originally appeared at CityLab. More from our sister site:

Fish can help slow down global warming—but not if we keep eating them

What if the best way to end drunk driving is to end driving?

The US economy finally hit a historic milestone—and it doesn’t matter