The US Supreme Court ruling striking down Roe v. Wade is nearly identical to the draft opinion that first leaked in May. But one tiny revision in justice Samuel Alito’s majority opinion is worth parsing because it reveals the problems with the interpretation of history proffered by the court’s conservative faction.

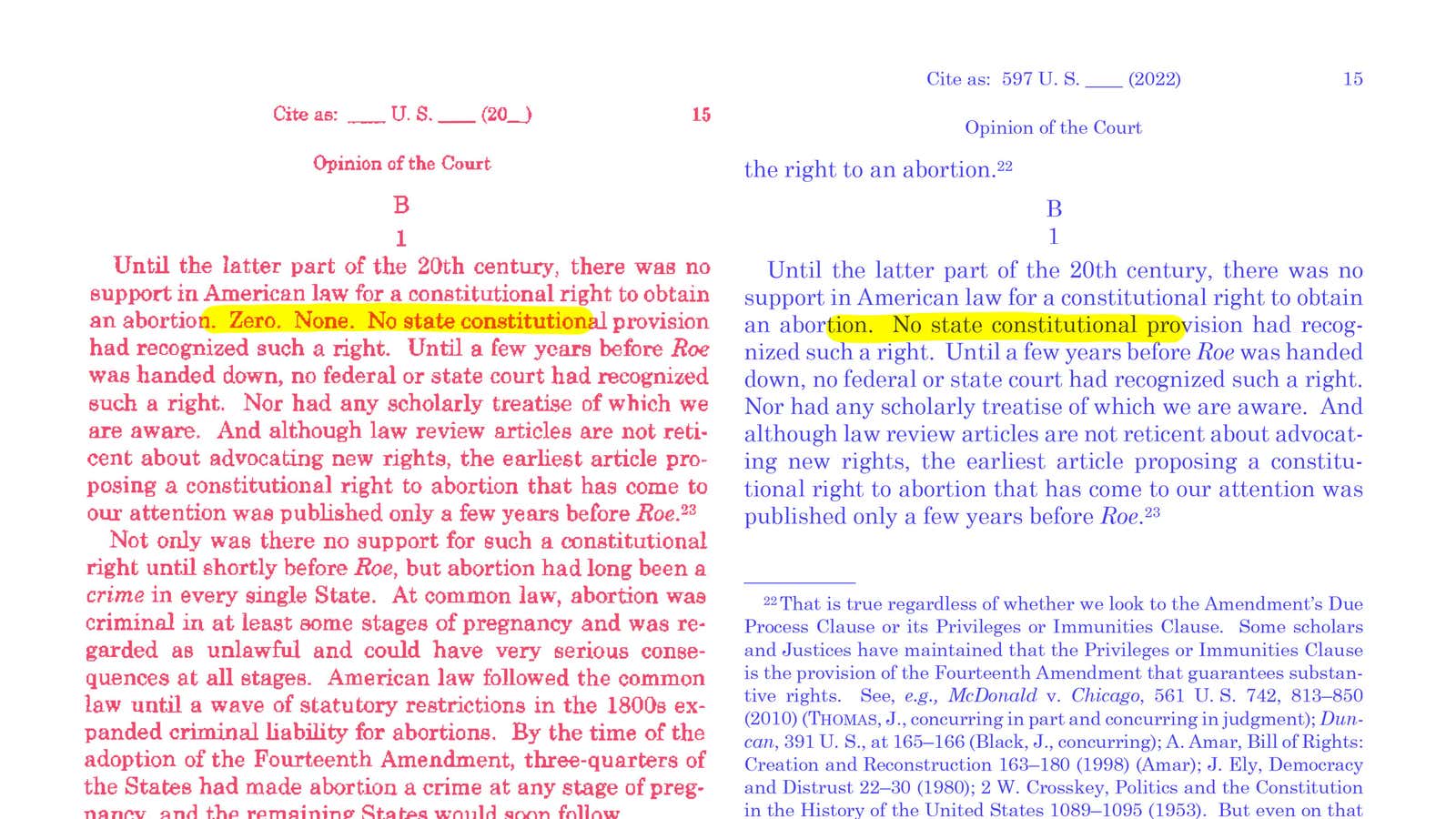

In the initial draft opinion, first obtained by Politico, Alito wrote, “Until the latter part of the 20th century, there was no support in American law for a constitutional right to obtain an abortion. Zero. None. No state constitutional provision had recognized such a right.”

In the final opinion released today (June 24), Alito slightly amended his wording: “Until the latter part of the 20th century, there was no support in American law for a constitutional right to obtain an abortion. No state constitutional provision had recognized such a right.”

What Alito gets wrong about abortion and US history

The elimination of the words “Zero. None.” may be more than a stylistic choice. In the aftermath of the leak, Alito’s emphatic assertion that American law provided absolutely no support for abortion rights until the late 20th century was met with criticism from some historians and legal scholars.

Alito, for example, claims that most states had prohibited abortion by 1868, when the 14th amendment took effect. But a legal brief filed by a group of historians in the case finds that as of 1868, “nearly half of the states continued either not to prohibit abortion entirely or to impose lesser punishments for abortions prior to quickening.” Quickening is a term for the stage at which a pregnant person can feel the fetus moving around, typically between 16 and 20 weeks.

Some historians also argue that Alito’s choice to focus on where abortion laws stood as of 1868 is arbitrary, given that abortion during the early months of pregnancy was accepted under common law during early US history. When states did begin introducing laws banning induced miscarriage in the 1820s and 1830s, the bans specifically applied to later-term abortions, according to historian Leslie J. Reagan. Not to mention that the laws were enacted before women had the right to vote in the US.

The extent to which laws governing reproductive rights hundreds of years ago ought to impact access to abortion today is a separate matter of debate. And Alito did ultimately stand by his historical claims. But his choice to strike two insistent words from his final opinion may be considered a tacit admission that the history of abortion in the US is not quite so clear-cut as he suggests.