China’s central government recently launched a ”war on pollution.” But at least when it comes to waterways, local officials don’t seem to have gotten the memo.

After test results for children in Dapu, a township in Hunan Province, revealed that more than 300 of them had hazardous levels of lead in their blood, the head of the local government had this to say:

“When kids are studying, they gnaw on their pencils—that also can cause lead poisoning,” Su Genlin, the official, told reporters (link in Chinese), dismissing concerns that a chemical plant had been dumping heavy metals into the local Xiangjiang River since 2012.

Never mind that children too young to go to school have lead poisoning. Or that a professional lab found airborne dust in the village to contain 22 times the legal limit of lead, while levels of lead, zinc, cadmium and arsenic in the factory drainage ditch, which flows into the village’s river, were all at three times the acceptable level (link in Chinese). Or, for that matter, that pencils have been made of graphite since the 1500s. (Su might have been confused because the Chinese word for pencil is literally “lead pen.”)

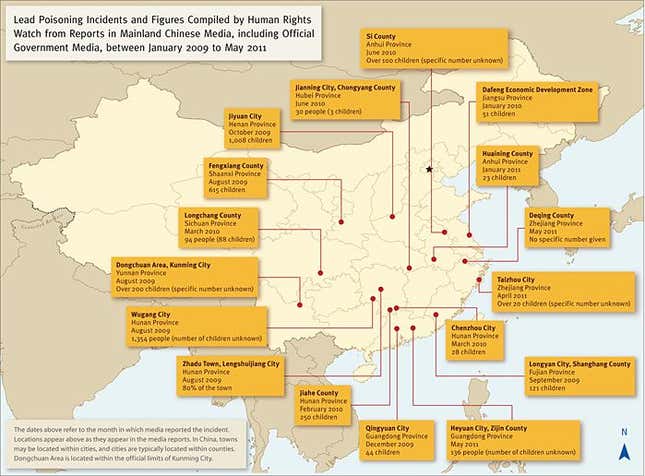

Villagers are outraged that their children have been subjected to a substance shown to cause liver, kidney, nerve and brain damage—and death. But they’re not alone. In the last few years, Hunan alone has seen many tens of thousands of children poisoned by lead linked to industrial waste. Lead poisoning is among China’s most common pediatric health problems, igniting protests around China in recent years.

Why is this happening?

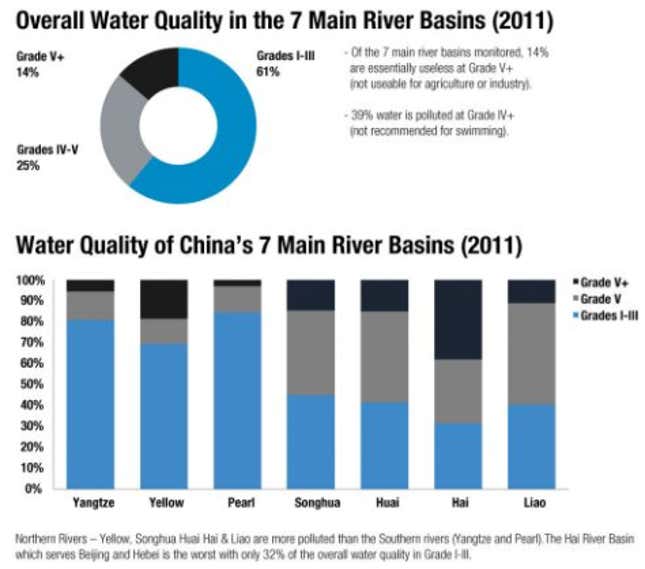

Industrial waste is expensive to dispose of, and government regulation has been lax. Now the water of more than three-quarters of major lakes and reservoirs (pdf) and two-fifths of major river basins is deemed unfit for human contact, reports China Water Risk, a conservation group. For instance, 70% of Hunan’s industrial output relies on the Xiangjiang River for water. A 2012 study found extremely hazardous levels of heavy metals throughout the Xiangjiang River basin.

And China’s problem is systemic, ingrained in its bureaucratic operations. Until recently, local officials gained promotion based solely on their ability to boost economic growth. That often has meant green-lighting industrial projects like Dapu’s chemical factory and encouraging maximum production, regardless of the environmental costs. In fact, Chinese media report (link in Chinese) that the local Dapu government okayed the plant in 2012, defying 2007 central government rules limiting the scale of such projects.

That’s changing. Last year, the central government said it would base promotions in part on officials’ environmental records, and pledged to punish violators.

After news of the tests in Dapu broke this week, one local environmental protection official told reporters that “basic plant management is up to standard,” and another asserted that compliance checks were conducted each week and that environmental officials at provincial, county and city levels all monitored the factory.

Still, the Dapu factory was shut down on Saturday after the Chinese media pounced on the story, and three environmental officials have been suspended. One local government down, a zillion to go. For 300 children in Dapu, the damage might already be done.