When a big organization rebrands itself, it’s usually a big undertaking. The whole process of conceiving and implementing a new design can take many months and cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. At the end of that, you’d think the last thing they’d want is to give away the design.

But that’s exactly what the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum is doing. And that decision is central to its new identity.

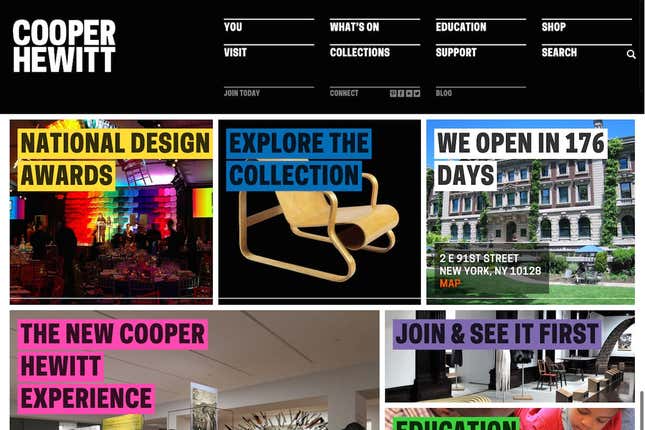

The New York–based museum, which reopens in December after a three-year renovation, commissioned a custom low-contrast sans-serif typeface from the designer Chester Jenkins for its logo, website, signage, and graphics. When the typeface (also called Cooper Hewitt) was announced last week, it was made available as a free download—not just the font, but its source files, which means designers can build on it. So far, it has been downloaded 1,200 times.

The museum’s director, Caroline Baumann, says distributing the typeface for free was a way to demonstrate the Cooper Hewitt’s commitment to its mission: “We’re all about giving the public access to great design—to our collection online, to our typeface, to our programs—and this was a natural step for us.”

It’s not a natural step for most type designers, who make their living by creating and licensing fonts. The Cooper Hewitt typeface is based on Galaxie Polaris (also designed by Jenkins), which starts at $300 for a standard license of a full set of styles; the price can go up dramatically from there, depending on how it’s being used.

Jenkins, who is the co-founder of Village, an independent type co-op with 11 member foundries, tells Quartz, “We don’t particularly like the idea of offering our work as free downloads, because it devalues the rest of the typefaces we offer and belittles the skill, time, and technical knowledge that goes into creating the typefaces we distribute.”

Still, he says, “What the Cooper Hewitt is doing here is quite a different thing—it’s a bold choice, really a revolutionary one.” Making the typeface available as a free download, he says, will feed a larger conversation about intellectual property and open-source models of design.

Eddie Opara, a partner at the design firm Pentagram, which handled the broader Cooper Hewitt identity, says the rebranding tried to represent the museum’s educational efforts visually. “They want to enable students and visitors to not just view work, but also engage with it and actually make their own work, and thus have their own dialogue,” he says. “How do you render that in a design?” The distribution model of the typeface was one answer.

He adds that, since Cooper Hewitt is a government institution, “utilizing a well-crafted, American-made product was important. And not something that’s Helvetica.” Jenkins echoes that sentiment: “The design was created for the Smithsonian, which is owned by the people of the United States, so the typeface should likewise belong to the people of the United States.”