Sweden’s hawkish central bank just morphed into a dove

In Sweden, the era of “sadomonetarism” is over. That is the ungenerous term coined by critics of the Riksbank, the country’s central bank, which they say has been more preoccupied with popping a property bubble than keeping an eye on inflation, jobs, and economic growth. Now it seems to be relenting.

In Sweden, the era of “sadomonetarism” is over. That is the ungenerous term coined by critics of the Riksbank, the country’s central bank, which they say has been more preoccupied with popping a property bubble than keeping an eye on inflation, jobs, and economic growth. Now it seems to be relenting.

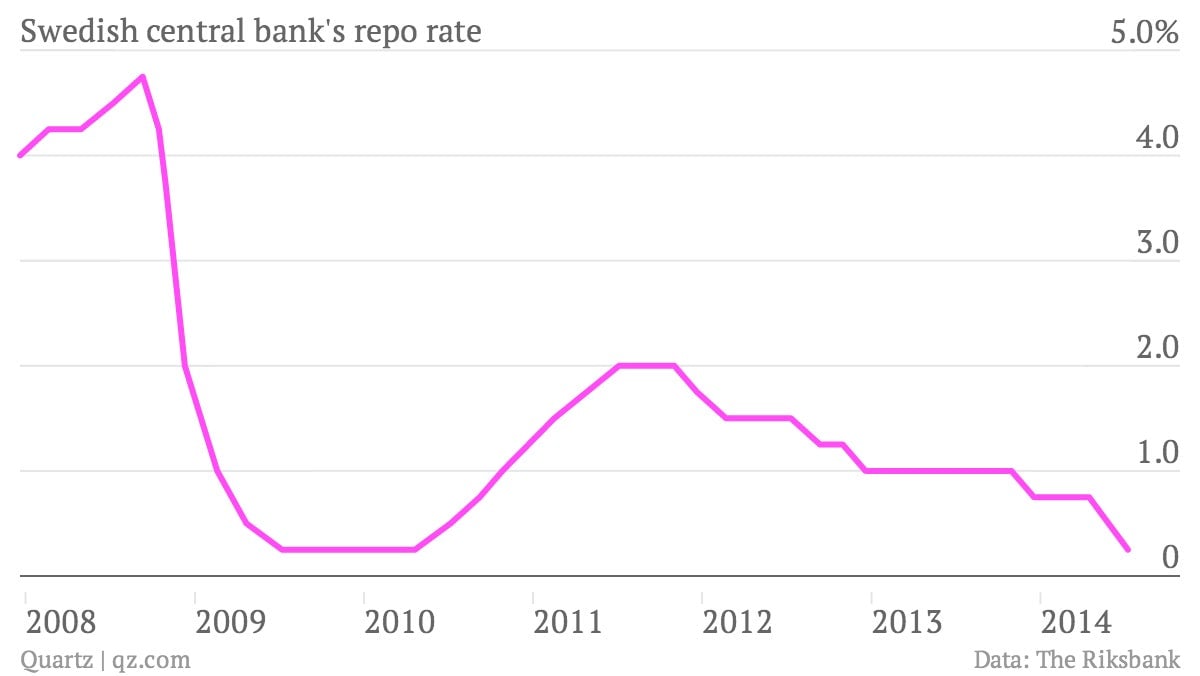

In 2010 and 2011, when the euro zone threatened to blow up and central banks in the US and UK printed billions of dollars and pounds to stimulate their economies, the Riksbank was running in the opposite direction, tightening its policy by hiking interest rates:

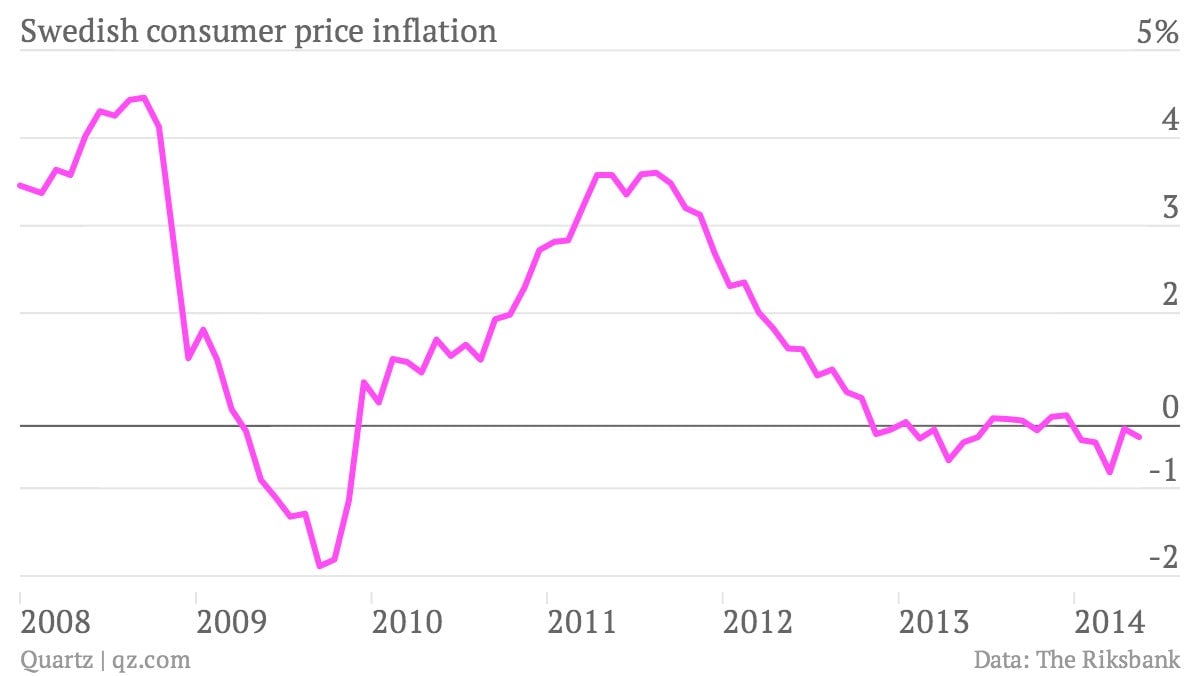

The upshot was that inflation steadily fell, and Sweden has been stuck in outright deflation for more than a year. As the case for tighter monetary policy became more difficult to defend, the central bank has reluctantly reversed course. Borrowers’ debt burdens remain high—at more than 170% of disposable income, on average—and lower rates could encourage them to grow even more. At the same time, deflation makes it harder to pay back these loans.

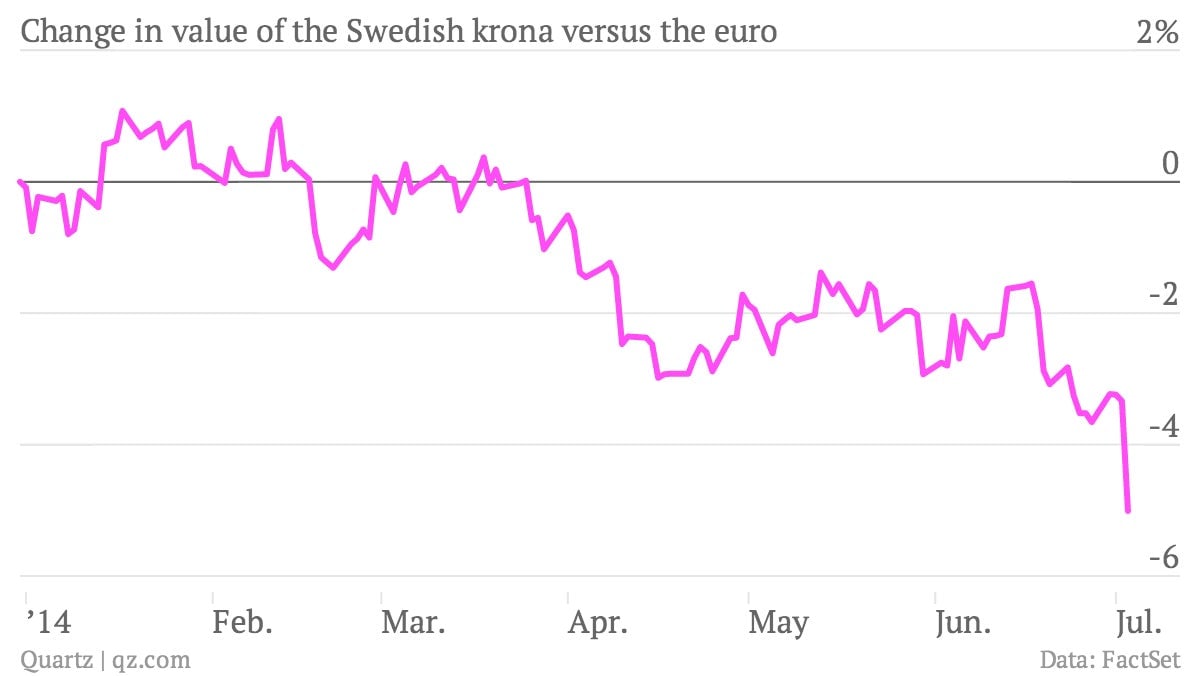

Today the Riksbank sprang a surprise by slashing its key rate much more than expected, from 0.75% to 0.25%. This brings the rate back to where it was before the hikes began. The markets weren’t expecting such a drastic move, sending the value of the krona down sharply:

Notably, Riskbank governor Stefan Ingves (pictured above) wanted a smaller rate cut but was outvoted by the rest of the board. This is grist for those, including former colleagues, who think he’s been far too hawkish in recent years. The central bank’s updated forecasts, published today (pdf), predicted that prices will fall by 0.1% this year, revised down from an expectation for modest inflation just a few months ago.

Today was the first time since the Riksbank became independent in 1999 that the governor was outvoted in a rate-setting decision, a sign that Sweden’s central bank is in the midst of something of an existential crisis. Unhappy with the bank’s hawkish stance, some politicians want to change its mandate to include targets on employment (akin to the “forward guidance” adopted by the Bank of England last year) and also to be given more of a say on who sits on the bank’s board.

But Ingves and his allies at the bank are still banging the drum about the country’s daunting debts and frothy property market. In today’s statement about the rate cut, the bank warned that lower rates could increase ”the risk of the economy developing in an unsustainable way in the long run.” An analyst told Bloomberg that lower rates could make already-high house prices “go bananas.” If that happens, it will be the sadomonetarists’ turn to say “I told you so.”