More and more US banks are getting out of the money-transfer business, Dealbook notes (paywall). A series of money-laundering scandals, punished by eye-popping fines, has made them cautious: Bank of America, HSBC, Citigroup and JP Morgan have pulled out altogether, while BBVA is reportedly looking to sell off a business unit that handles wire transfers in Latin America. And the fear is that rules intended to stop terrorists and drug traffickers are disproportionately hurting the families—and home countries—of migrants in the US who send money back home.

But the risk of accidentally doing business with a drug cartel is only half the reason the banks are getting out of this game. The other half is competition from new companies. The World Bank’s most recent report (pdf) shows that the average cost of sending money from the United States in the second quarter of 2014 was 5.78% of the sum sent—down from an average of 7.21% just five years ago. That puts the squeeze on margins just as banks are trying to consolidate into the most profitable activities.

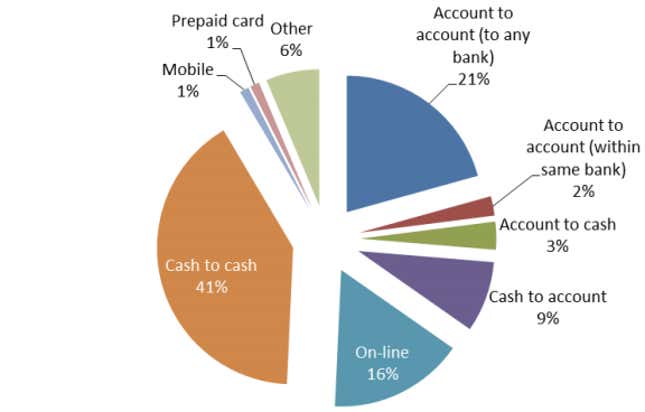

The report also includes this chart, showing what tools migrants around the world could use to send money back to their families in that period. Only 26% had access to a bank (the “account-to-account” and “account-to-cash” segments in the chart). The analysts write that cheaper alternatives to banks, in particular online services, have grown from previous samples:

It may also be that banks were tricked by statistics suggesting that this business was booming far more than it actually is. Bank of America said it retired its cheap service for sending money to Mexico because of “limited demand.” One reason for that limited demand may be that, according to one World Bank research paper, nearly 80% of the increase in US remittances to Mexico between 1990 and 2010 was “an illusion”—the result of changes in how banks reported the data. (Ironically, the changes were inspired by post-9/11 reforms intended to prevent terrorist financing.) Between 2000 and 2006 remittances to Mexico supposedly nearly tripled, but real flows increased by only 37%.

The study documenting that discrepancy came about when development economists couldn’t find any evidence that the massive surge of money from migrants was helping economic growth in their home countries. The “extremely clear implication,” one of the authors, Michael Clemens, tells Quartz, is that policymakers are “never going to increase remittances by 50% by making them cheaper. The only way to do that is that if more people are able to move and take advantage of the gigantic investment opportunity” that legal employment in a wealthy economy represents for citizens of poorer nations.

Therefore, while cutting the cost of remittances is a popular way to promote development—and, of course, matters to the people sending them—it’s more important, Clemens says, to have more people in a position to send them at all. And that is a far more controversial problem.