Somewhere in the South China Sea, an oil tanker carrying 1,160 barrels of fuel went missing on July 4. The Honduran vessel the Moresby 9 was boarded by attackers, and by the time the Indonesian navy arrived, it had disappeared. Its location is still unknown. The apparent hijacking appears to be the latest in a string by highly skilled pirates who troll the region looking for one specific thing: oil.

In the past few months, sophisticated pirates have hijacked eight tankers in the South China Sea and Malacca Strait, mostly for their marine gas oil (MGO)—a fuel similar to diesel—and other refined petroleum. These attacks aren’t smash-and-grab robberies, where pirates snatch cash, laptops and cellphones and then make a quick getaway. These pirates follow a different and more lucrative business model: They commandeer the whole tanker, take it to a secret location, and expertly drain it of its oil.

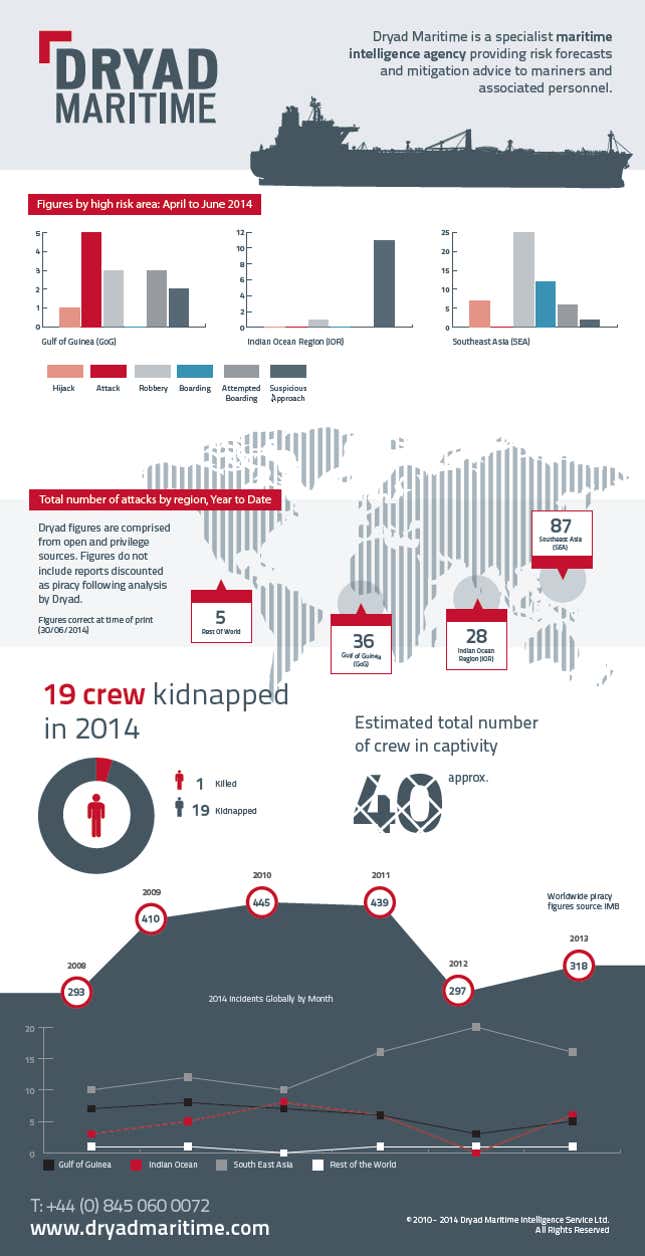

While piracy off Africa’s coasts tends to get more attention (and even lately the Hollywood treatment), Indonesia’s waters actually saw the most attacks worldwide in the first quarter of 2014. Southeast Asia is the region with by far the highest numbers of attacks, as shown in the infographic below, by the British research company Dryad Maritime Intelligence Services.

Experts have warned that these Asian pirates’ attacks are intricately pre-planned and complex. They’re relatively non-violent compared to those in West Africa, and although crew members have been held hostage, none have been killed.

James Bridger, a maritime security consultant at Delex Systems Inc., said the common modus operandi used by these pirates indicates that the attacks are likely the work of one gang that’s receiving information and paychecks from a crime syndicate with roots in Indonesia and ties to Singapore. Since no pirate, nor anyone from this alleged crime syndicate, has been caught, not much is actually known about them, but Bridger tells Quartz that the pirates are likely to be from Indonesia. They also seem to know when the vessels are leaving the port in Singapore, suggesting they’re getting intel from there.

These pirates target small tankers with low decks, which make them easy to board. And once they hijack the ship, they make it disappear for some time—a few hours to a couple days. They paint over the vessel’s name to hide its original identity, keep the whole crew hostage, and efficiently siphon off the oil, Bridger said.

Stealing a tanker of oil via ship-to-ship (STS) transfer is no easy task. Not only does it require a pirate tanker to meet the hijacked vessel at a predetermined location and time, but it also necessitates a properly trained crew to make the transfer. Only expert engineers or crews with experience in this field could pull off such a thing.

But it’s probably not too difficult to recruit these ship-to-ship transfer experts, Bridger believes. They are simply able to make far more money working for pirates than at above-board jobs. “Perhaps they already knew each other from other elements of the black market fuel game, or it’s possible that the STS experts are ‘moonlighting’ with the pirates while still keeping their regular jobs,” he said.

Once taken, Bridger said, the oil is sold on the regional black market—Singapore, Malaysia, Borneo, Thailand and Vietnam. High oil prices in Singapore have nurtured a very large black market for fuel.

The city-state, with one of the world’s busiest ports driving its economy, has plenty to lose if it doesn’t address its piracy problem. With most of the attacked ships coming out of Singapore, the port could be classified as high-risk, which would mean a greater premium for ships’ insurance and diminished traffic.

With these pirates’ exceptional success rate so far, Bridger says these types of attacks will probably continue, at least through the dry season of March to October, when waters are calmer. Analysts at Dryad also point to a lack of effective law enforcement in the region. According to their recent report, ”Dryad is not expecting to see the level of maritime crime to fall in this region for the remainder of the year unless there is significant investment by local maritime forces in proactively countering this crime.”