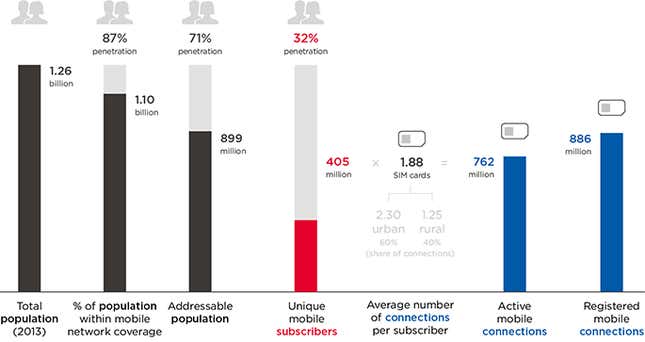

There are 7.18 billion human beings on the planet today. And there are 7.07 billion mobile phone connections. But those belong to fewer than 3.6 billion unique subscribers, or just over half the earth’s population. Some of that other half of humanity without mobile phones are children, the elderly, or neo-luddites. But many more are simply too poor to afford a phone. For the 2.4 billion people who live on less than $2 a day, even the cheapest, most basic mobile phone is half a month’s wages.

But what if these people could get a mobile phone subscription without having to spend money on an actual phone? That would be good for those new subscribers—the benefits of connectivity to poor populations have been well-documented—and it would be good for mobile operators, which would find a new revenue stream from a previously untapped market.

Movirtu, a six-year-old company based in London, says it has the answer: virtual SIM cards that can be used on borrowed or shared phones. And Airtel, one of the world’s largest mobile networks, thinks Movirtu is right. Last month, Airtel signed a deal to bring Movirtu’s technology to the 17 African countries in which it operates. The system is already live in Madagascar and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Carsten Brinkschulte, Movirtu’s CEO, says it has signed agreements with three other operators in Africa and Europe, though he cannot name them for legal reasons. The unnamed European operator will start its virtual SIM service by the second half of this year.

Like an email account for phones

Here’s how it works, for US readers (all others can skip to the next paragraph): Outside of the United States, almost every mobile network in the world operates on a GSM network, one of two standards for mobile phone connectivity. Unlike CDMA, which is used by big American carriers, GSM is linked not to the device but to a little chip that must be inserted into it, known as a Subscriber Identity Module (SIM) card.

Until recently, the only way for many in the world to use a phone number without owning an actual phone has been to obtain a SIM card, borrow a phone, remove the owner’s SIM, and replace it with your own. (In cheaper phones, the SIM is often located deep within the phone, beneath the phone’s battery, held in by a flimsy piece of metal.) Then, after using the phone, you go through the whole fiddly process in reverse and return the phone. It is a cumbersome exercise.

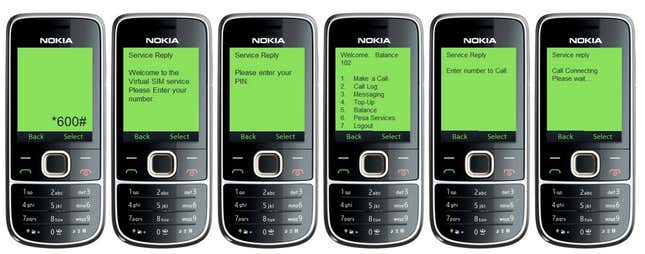

Movirtu does away with the requirement for a physical SIM card. Instead, it allows operators to sell virtual SIMs, which exist only as numbers. To use one, a subscriber simply borrows a phone and enters a short USSD code which tells the network that the phone is now using another number. The subscriber can then make and receive calls from his own number (at his own expense) on the borrowed phone. All that’s changed is an entry in the mobile network’s visitor location register, a backend database. To return the phone, the subscriber must enter the code again, and all is back to normal. Think of it as logging into your email account from a friend’s computer.

More realistic than waltzing up to a stranger and asking to borrow their phone is the use of virtual SIMs by families or communities. As children grow older and demand their own phones, families could get them virtual numbers so they have their own identity, without having to invest in extra devices. Or a group of a few people could share the price of a phone and use it with their individual SIMs.

And here’s the crucial bit: Since Movirtu’s technology relies on the mobile network, it doesn’t need an internet connection. Most other companies that offer virtual phone numbers (such as Skype) use Voice-over-Internet-Protocol (VoIP) or WebRTC, both standards that need the internet to work. But data costs money, connections depend on network connections, and data services are expensive when roaming.

Multiple identities

Movirtu is not the first company to try virtual SIMs. Back in 2008, Comviva, an Indian firm then owned by Airtel, tied up with MTN, a large African mobile network, to offer virtual SIMs in Cameroon. By late 2009, it was claiming 30,000 virtual SIM subscribers (pdf). The service also launched in Ghana in 2010. In Cameroon, MTN now offers a ”dual account” service, but it is only available as an extra service to people with existing physical SIM cards, not to those without devices. There has been little news from Comviva since 2009, though a company representative says the service continues.

But things are different now. For one thing, mobile phone subscribers have become accustomed to the notion of multiple numbers thanks the proliferation of to dual- and multi-SIM phones, which were still a novelty in 2008. And mobile subscribers in the poor world now routinely have two or more mobile connections to take advantage of differing tariffs on different networks. In Nigeria, the average subscriber has 2.39 SIMs. In Indonesia, it’s 2.62, according to the GSM Association (GSMA), a trade body of the world’s mobile operators. Movirtu’s Brinkschulte says the average for Africa as a whole is 1.4. “We think we can increase that further to two or three [SIMs per subscriber]. We think the overall potential is very large,” he says.

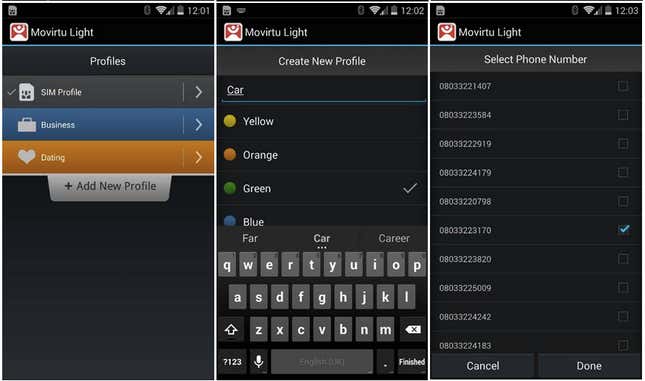

As people have become used to multiple SIMs for different call rates, they have also come to appreciate the benefits of having different numbers for different purposes, such as separating their work and personal lives.

A number for every occasion

Movirtu is also thinking beyond the poor world, though it is unclear whether Western consumers will bite: with smartphones and unlimited data plans commonplace, and with web-based alternative numbers easily available, Movirtu will need to make a pretty strong pitch to convince consumers and businesses that a separate network connection is necessary.

And indeed, there are some situations, even in the West, where a virtual SIM could come in handy. Many large Western companies now allow users to use their own phones for work purposes rather than carry a company-issued device as well. But for employees, that means the hassle of expensing partial phone bills; and for companies, the inability to take advantage of the corporate rates that come with bulk subscriptions. (It also means that when an employee leaves the company, she takes the number and her contacts with her.)

A virtual SIM makes it possible to carry just one phone, with a work and a personal number on it. It could receive calls on either number at any time, though would need to be told which number to call from. Movirtu’s smartphone apps make the process of switching numbers even easier than entering a code, and the fact that it works on mobile networks rather than over the internet means it is more robust and unaffected by slow data connections. Moreover, it is cheaper to pay call roaming rates than data roaming rates (necessary for services such as Skype) when you travel abroad.

Another practical application of virtual SIMs involves privacy. “If you want to sell your car, you probably want to give a number where potential buyers can call you,” Brinkschulte says. “But you may not want to expose your number to the whole world.” It could be useful for dating, he says. Criminals and adulterers might also find a virtual SIM handy.

We’ve come to learn over the past few years of struggling with maintaining our social media presences that human beings have different identities for different social situations—something Google+ tried to remedy with “circles.” Pretty soon we may also have a different phone number for each of our personal circles.