Everyone is trying to revolutionize education. And they’re spending billions of dollars to do it. But entrepreneurs, investors, big companies, non-profits, government, and even schools are focused on the wrong issue: How to make education more accessible. That’s not the real problem anymore. So businesses with that goal might not turn out to be good investments either.

The problems with education today are relevance and, more importantly, effectiveness. The world has changed. You can blame technology, globalization, demographics, government debt, or whatever you want, but to succeed in the world of today and tomorrow, people need more knowledge, new skills, and broader capabilities than they needed yesterday. What they need is simple. It’s getting there that’s not.

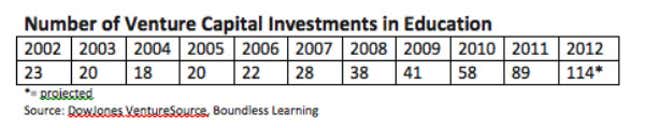

The traditional education system can’t afford to fix these problems on its own. That, of course, means big opportunities for those who can. In the US alone, venture capitalists have invested more than $2.8 billion in 236 new education companies over the last 10 years. And the pace is accelerating. In 2002, VCs made 23 such investments. This year, they’re on pace for 114 deals, 30% more than last year. Angel investors are seeding hundreds more. But with a few notable exceptions, very little of this effort is focused on fixing the imbalance in supply and demand for 21st century skills such as science, technology, engineering, math, foreign languages, and entrepreneurship.

The most visible (and lucrative) product of such investments is new educational institutions. “Traditional,” for-profit universities like the University of Phoenix, Kaplan University and DeVry University have enrolled millions of people over the last few decades who otherwise wouldn’t or couldn’t have gotten a college education. They did that, in large part, by focusing on in-demand vocational skills and leveraging technology to make instruction more accessible for non-traditional adult learners, who need more flexible scheduling options than 18-year-olds. That was an important innovation since more and more jobs will require more and more education.

They made billions of dollars along the way, too—mostly from Americans’ tax dollars funneled through government financial aid. Which would be fine, except they weren’t very effective. A lot of their students racked up enormous student debts to get educations that they either didn’t finish or get much use from. The majority of students who enroll at the for-profit colleges leave without a degree, according to a recent Senate report on the industry, and these students account for around 47% of defaults on student loans in the US even though they only make up 13% of college enrollments. That has fueled intense, sustained government and media scrutiny about questionable recruiting practices and academic quality. And that, together with increasing competition, has led to a big drop off in enrollments and therefore profits at most of the big for-profit schools.

There’s a new crop of alternative institutions that aim to do better. The Minerva Project, a new start-up for-profit college backed by $25 million in VC money, aims to provide an elite global education, largely online, to rival the Ivy League. And UK-based upstart New College of the Humanities, a “quasi-non-profit” college with £10 million in seed money from 28 investors is similarly focused on providing rigorous, high-quality instruction to better-prepared students. That’s no doubt worthwhile. But despite an emphasis on online delivery and more flexible, variable cost structures, it’s hard to see how they will scale into huge, highly profitable businesses like their predecessors. It’s still difficult, expensive and labor-intensive to create and deliver knowledge and to provide personalized feedback—even with technology. And at least at the start, they’re both focused on liberal arts—which isn’t where the jobs are.

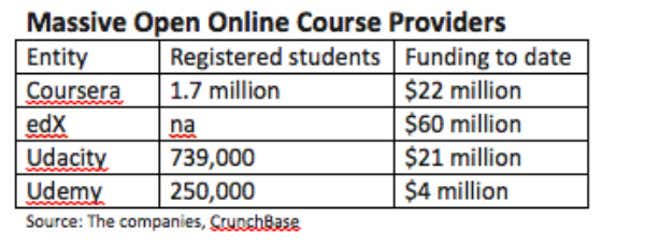

There’s also a lot of money pouring into new companies providing infrastructure and services to amplify the reach of existing educators. In just the last few years, for example, professors from elite schools, including Stanford, Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, have registered more than 2 million students from all around the world in so-called Massive Open Online Courses (“MOOCs”), mostly on computer science and engineering. Those courses are being delivered by new entities such as Coursera, edX, Udacity, and Udemy that aggregate the course materials from schools as well as individual academics and then market them to people across the globe. Given their growing popularity, these platforms, mostly set up as businesses, have collectively attracted the media’s adoration and more than $100 million in funding.

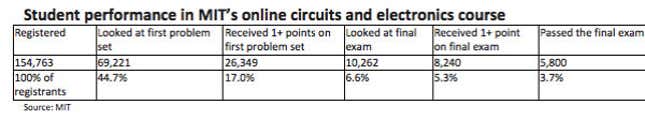

But two things get a lot less attention. First, very few, if any, of those people are paying. There is talk of sponsorship fees to match employers with skilled students and charging to certify completion. That last one that raises the second issue, though: Only a fraction of those who sign up do any of the coursework and fewer still are completing the courses. In MIT’s first online course, for example, fewer than half of the 154,000 students who registered even looked at the first problem set and less than 4% passed the final exam. Those attrition rates are similar to what you see in many for-credit, fee-based online courses.

So in simple terms, the online courses, or MOOCs, dramatically increase the supply of education. But they have, at best, a marginal impact on demand, revenues, or costs (the schools still have to spend money to produce the required videos and other materials). And although it’s still early days, they have so far had a questionable impact on the value of education.

One reason is that so far, the majority of the innovation has gone into the technology, not creating better content or more effective learning experiences. Most of these online courses are basically video replays of existing lectures with accompanying class PowerPoint slides, notes and assignments. That’s not really new; people have been doing that, beginning with TV, as far back as the 1960s. More importantly, though, it’s just not in sync with the behavior of today’s easily-distracted, attention-deficient, always-on, mobile, social learners.

There are, of course, exceptions to that rule. Udacity, one of the leading providers of MOOCs, for example, says its approach to teaching focuses on solving problems and getting instant feedback. Khan Academy, a free, online library of more than 3,500 videos on everything from arithmetic to physics, finance, and history, gets high praise for breaking difficult math concepts down into short, easily understood lessons, which have been watched over 200 million times. And Codecademy is teaching millions of people the basics of computer programming one command at a time. Leaving aside questions about their effectiveness, though, few of these actually generate much, if any, revenue yet.

Lynda.com does make real money. It’s a fast-growing, $70 million business built on short, entertaining, on-demand video lessons on creative skills and design software. So does General Assembly, a network of “campuses” where would-be entrepreneurs can learn about technology, business and design. More than 10,000 people have paid anywhere from $20 to $3,000 and up for their short, live classes and longer certificate programs. And more than 80,000 people have reportedly signed up to take Lean LaunchPad, an online boot camp that aims to turn out fully functioning start-up businesses in 10 weeks. There are others, too. However, they’re still more the exceptions than the rule.

Despite all these new educational options, almost half of US employers say they can’t find workers to fill more than 3 million positions, even with 13 million Americans unemployed. A good chunk of that is due to what business and politicians call the “skills gap.” Around 12% of factory-floor jobs, for example, now require a higher level of skills than similar jobs required just a decade ago, according to the National Association of Manufacturers. And it’s not just blue-collar workers, and technicians. It’s computer engineers, biochemists, market research managers, and salespeople, too. More than half of the fastest-growing occupations in the coming decades will require at least moderate preparation, according to consultants at Deloitte.

Schools and employers’ own training programs aren’t keeping up. At the low-end of the wage scale, state and local governments and non-profits have begun offering accelerated programs, in the specialized manufacturing skills companies desperately need today, to retrain displaced workers who can’t wait two to four years for a degree (even if they can afford it). At the higher-end, employers can’t find enough digital-savvy marketers, computer programmers and health care administrators. So companies like GE, American Express and ad agency Kirshenbaum Bond Senecal + Partners are now sending employees to General Assembly for corporate training programs. Silicon Valley tech companies are beginning to pay online course providers to match them with high-performing students “certified” in the latest programming languages. And nurses go to Wharton School of Business executive education programs sponsored by Johnson & Johnson.

This flurry of innovation, entrepreneurial activity and investment directed at improving education is exciting. And in the long term, it will probably change education for the better. But it hasn’t begun to make a dent in the mismatch between the demand for and supply of 21st century skills. If we want to do that, then we need to focus more attention on two things.

First, we need more focus on creating and delivering the right knowledge and skills. Between start-ups, government, and non-profit initiatives and changes in curricula at all levels of the educational system, that’s starting to happen. There are more options for learning about computer programming, design, foreign languages, and entrepreneurship today than ever before. However, there’s been inadequate efforts to address critical shortages in some other in-demand areas, such as advanced manufacturing, math, engineering, biological sciences, digital marketing, and global business.

Second, we need to do a better job of improving the engagement with—and more importantly, the effectiveness of—our educational experiences, both old and new. Students today learn differently than the students of just a decade ago. As we’re seeing, technology, video and badges alone are not enough to keep learners’ attention or to improve educational outcomes. They need to be paired with a deep, up-to-date understanding of how students actually learn.

When we do that, we’ll start to turn out much more useful and sustainable education businesses. And that will be really disruptive.