As president of China and general secretary of the Communist Party for more than a year, Xi Jinping has presided over a far-reaching anti-corruption campaign that has detained tens of thousands of officials and executives from state owned enterprises.

Despite warnings earlier this year from both his living predecessors and political analysts that it might be time to “call off the dogs,” Xi has only gone further since then, ousting the biggest “tiger” yet in June, when Gen. Xu Caihou, vice chairman of the Central Military Commission, was suspended for suspected bribery. While the People’s Liberation Army newspaper dutifully endorsed the suspension, a series of recent reports suggest that the unrelenting campaign and Xi’s single-minded consolidation of power are causing serious unrest inside the top echelons of the party.

The reports are nearly all anonymously sourced, so it is impossible to pin down who exactly is upset with Xi, but even before his relentless anti-corruption campaign, the party was often characterized as riven by numerous factions. The fact that Chinese officials and analysts are talking in the first place, and especially to researchers and reporters from foreign media outlets that aren’t likely to soft-pedal the complaints, indicates that the dissatisfaction with Xi’s policies is high. Here’s some signs he may have a popularity problem in the top ranks:

- The corruption probe is viewed as political. Officials now “intend to defend” a probe into former Politburo Standing Committee member Zhou Yongkang at an annual party meeting this year, senior law enforcement and propaganda officials told the South China Morning Post, by saying the inquiry “followed the party’s constitution and was not driven by a political power struggle.” The probe into Zhou is so divisive within the party that the planning session may be moved up from its traditional November date to the end of August to address the issue, they said.

- Nothing is getting done. Much-needed economic reforms and running the daily machinery of government are stalling. Officials are so fearful of being caught up in the far-reaching corruption crackdown they’re “dragging their feet because they are scared” of attracting attention, unnamed bureaucratic sources and officials at state-owned enterprises told Reuters this month. “There is an atmosphere of fear and uncertainty,” one civil servant said.

- Xi is being compared to royalty. Unlike Xi’s predecessor Hu Jintao, who emphasized collective decision making with the Standing Committee, Xi has positioned himself as the “emperor” of the Standing Committee, with “six assistants,” a Chinese academic told The New York Times.

- Party members are looking for ways out. Faced with the choice of being demoted or bringing their families back to China, so-called “naked officials” are choosing to leave the party. Chinese media report that 54 Communist Party officials died of “unnatural causes” in 2013, and of those 23 were believed to be suicides. The rash of suicides comes as “strains on the rank-and-file appear to have gotten even more oppressive amidst Beijing’s demands that cadres labor harder, govern more effectively, and behave better,” the dean at the Beijing Center for Chinese studies wrote in The Wall Street Journal.

Some political analysts are making dire predictions. “Xi needs to placate the malcontent within the Party by slowing down,” the World Policy Institute recommends, or face a “political crisis.” Gordon Chang, a well-known China bear, writes that “Xi, it seems, is in the midst of destroying all other power centers in the country’s ruling organization, firmly rejecting the live-and-let-live mentality that has kept peace in Beijing since the sentencing of the Gang of Four in early 1981.”

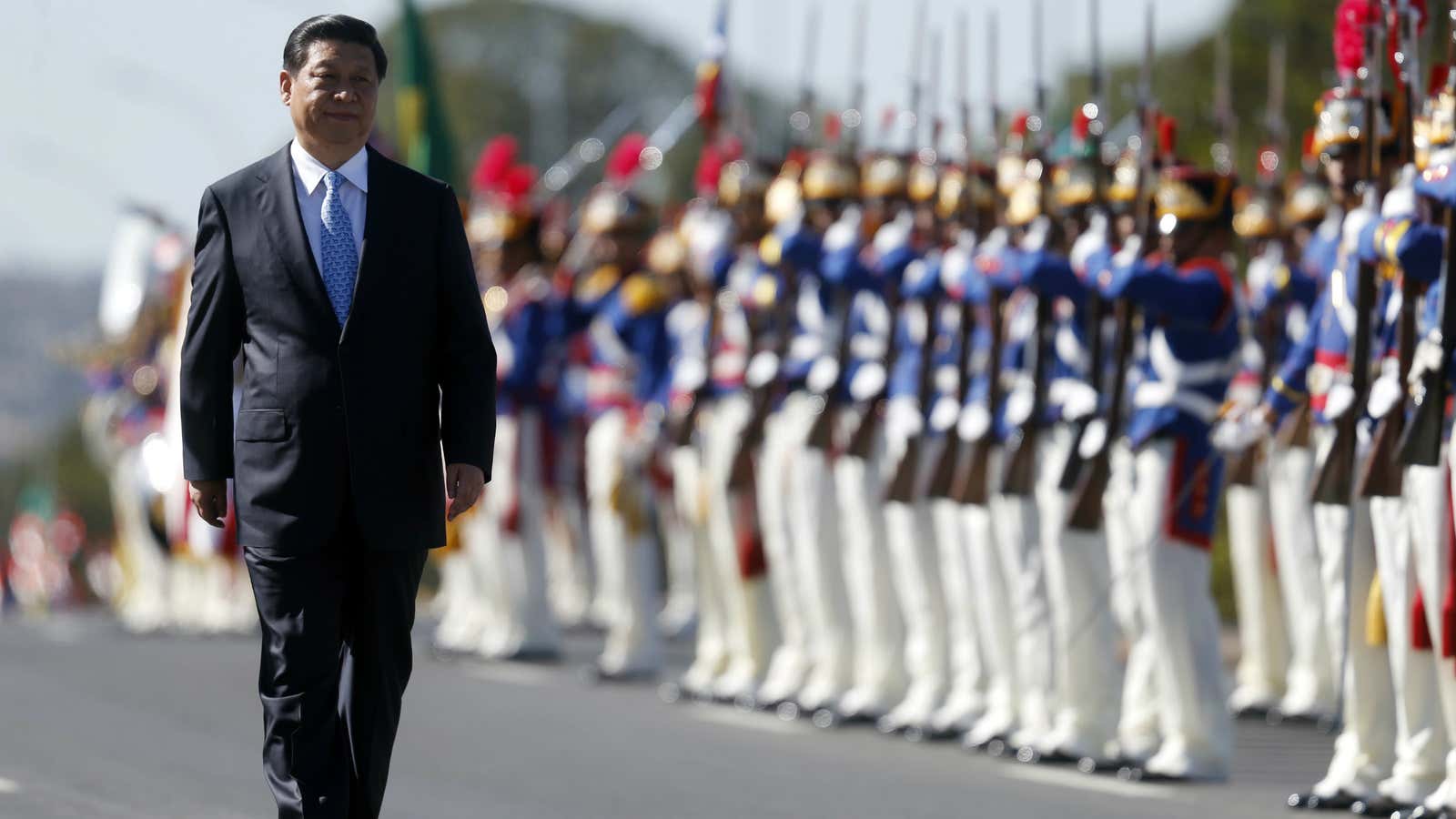

As with so many things about the inner workings of the Communist Party (and, really almost any political party in the world) there’s much going on behind the scenes that is unlikely to ever be made public. While the nearly 3,000 members of the National People’s Congress officially voted to elect Xi in 2013, the vote was a formality. His ascension was decided in 2007 by his predecessor and his predecessor’s predecessor and like them, he is expected to serve two five-year terms.

But Communist Party history, and modern political history of China, are rife with upheaval at the top. Two of the last four leaders did not serve two terms because they were forced out of their positions.

Perhaps tellingly, as reports about unrest within the party are cropping up, Beijing has tried to crack down on what Chinese journalists can report about “state secrets,” and told them not to work with foreign media. Most recently, the government shut dozens of news and information websites for circulating “political rumors.”