Long before Gwyneth had Goop or Martha Stewart was Martha Stewart, a broad-hipped caramel blonde from Massachusetts stormed America’s kitchen culture. She was no genetically gifted life coach or goddess of domesticity. In the 1930s, the original culinary cash cow was actually, well, a cow. Her name was Elsie.

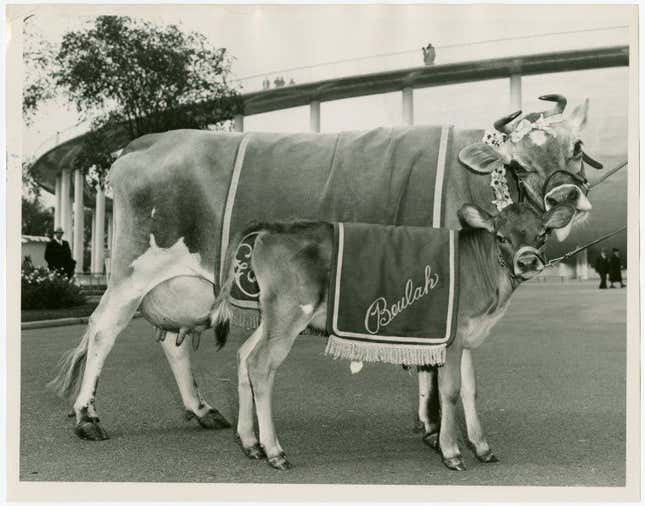

Elsie the Cow was born out of a crisis. When Borden Dairy, a powerful milk and cheese processor, found itself in a pricing war with northeastern dairy farmers, the company needed to keep public opinion on its side. Enter Elsie: a bright-eyed, anthropomorphic cartoon cow who appeared in advertisements and captivated fans with her signature daisy necklace, jaunty horns and coquettish smile.

“I’ll show you how to sweeten dispositions in your house!” Elsie told housewives in Woman’s Day, beaming in a pink ruffled apron with a steaming cup of coffee, as she sent her husband, Elmer the Bull, off to work as the emblem of Elmer’s Glue (also a Borden property).

When I was a little girl, our dining room in St. Louis housed a trove of Elsie memorabilia—my mother’s reminders of the upstate New York dairy farm where she grew up.

Elsie smiled at me from a vintage sign and beamed from behind the wheel of rickety toy milk truck. They were antiques, my mom told me, too fragile to play with. But unable to resist, I would sneak the truck off the shelf and gently push it across the floor before returning it to rest alongside the faded aprons, worn cookbooks, and porcelain cups.

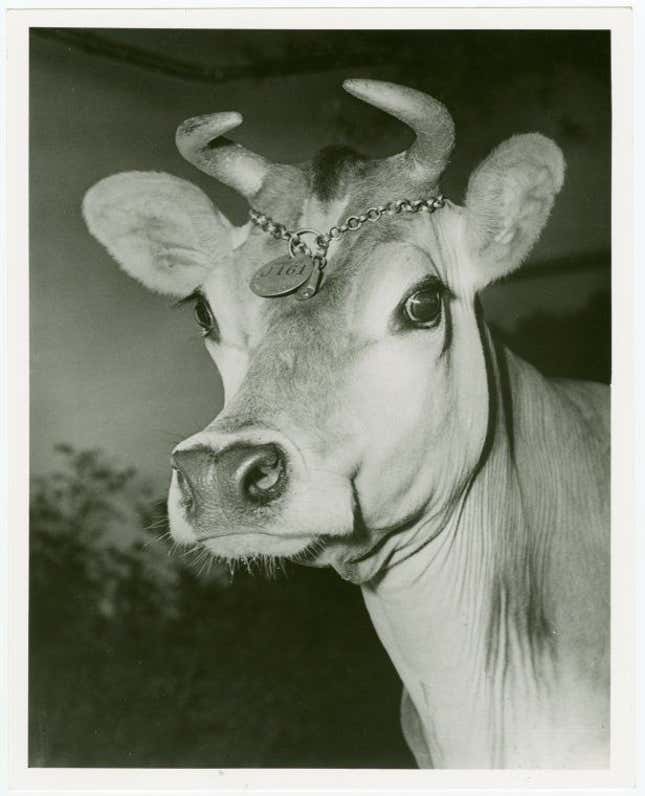

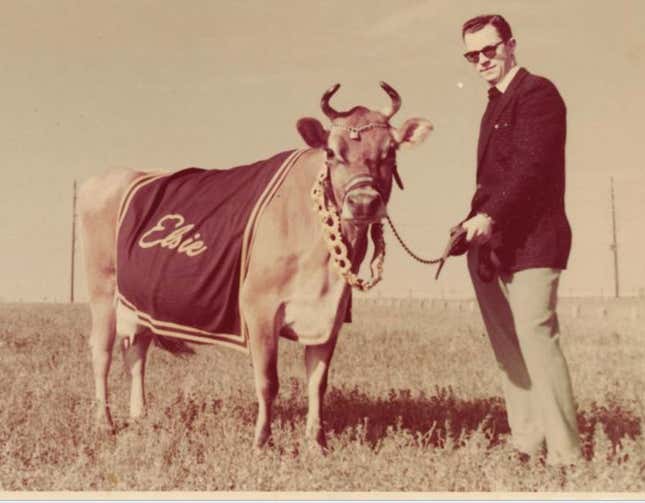

I wasn’t the only one charmed by Elsie’s long-lashed gaze. Elsie not only helped Borden survive the “milk wars” of the 1930s, she became a potent symbol for the dairy industry, and for Jerseys, her breed of small, creamy-coffee-colored cows. And like a velveteen rabbit of marketing mascots, the adoration of Elsie’s fans brought her to real life—much to Borden’s surprise.

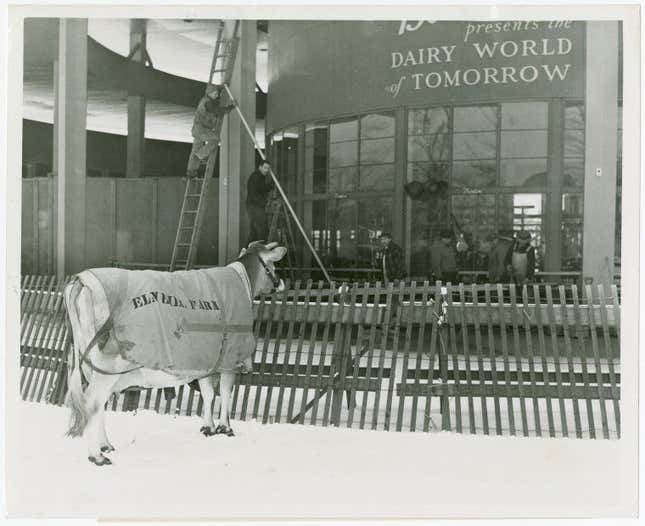

At the 1939 World’s Fair, the powers at Borden had planned to impress fairgoers with the Rotolactor: a futuristic automated merry-go-round milking machine with live cows on top. But spectators had just one question for James Cavanaugh, a young agricultural student who was working at the exhibit.

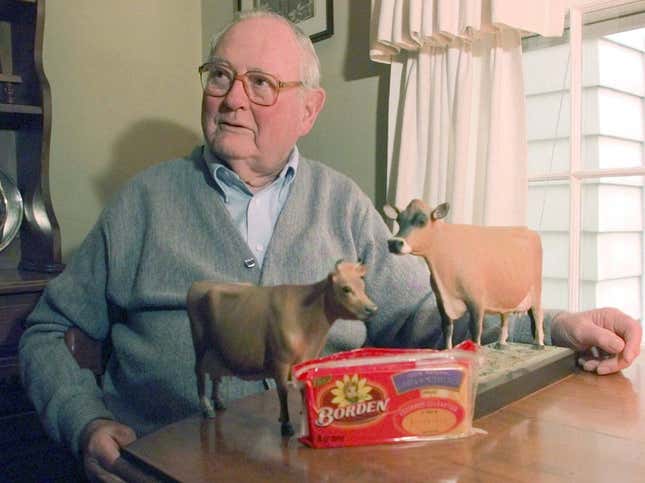

“People would come and say, ‘Which one’s Elsie?’” remembered Cavanaugh 70 years later, in 2009. When we spoke, he was 92 years old and retired after a long career in the industry, advocating for farmers and breeders of Jersey cattle.

That day on the floor of the 1939 World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows, Queens, the young Cavanaugh considered the cows before him, he recalled, and christened one Elsie to please the crowd. “She looked at people instead of just letting them look at her,” Cavanaugh told me over the phone, a year before he passed away. “She was a personality cow.”

Agricultural technology companies may still be trying to perfect that swirling, space-age milking machine, but it was the steady gaze of a beautiful bovine that caught the attention of Americans. By the end of 1939, over 7 million people had taken in one of Elsie’s live appearances. James Cavanaugh said that many of those people, who knew Elsie from Borden’s advertisements, had never seen a live cow before. A cartoon cow in a ruffled apron might seem unsophisticated, but almost seven decades before the advent of The Omnivore’s Dilemma, Elsie had succeeded in introducing Americans to their food source.

“Going back 50 years or so,” said Cavanaugh, “they say more people recognized Elsie than they did the president.”

Like a modern-day celebrity, Elsie made appearances in the movies, had public pregnancies—twins!—and even co-authored a cookbook in 1952. Jane Nickerson, then the food editor of The New York Times, reviewed Elsie’s book the same day as the British cookbook author Elizabeth David’s now-renowned French Country Cooking. She seemed to prefer Elsie’s folksy recipes, such as squirrel with parsley, to David’s “discursive” style.

A rotating cast of cows played Elsie throughout the years, but when the original Elsie died in 1941, the Times commemorated her career with an obituary worthy of any performer or public servant. One of Advertising Age’s Top 10 Icons of the 20th century, Elsie was an early example of what today we call branding. (In the marketing sense, not the livestock sense.)

In the decades since Elsie encouraged dairy lovers to cool off with a refreshing glass of buttermilk, Borden has gone through several corporate takeovers. Today, a handful of companies have the license to use Elsie’s name and image. She appears on packages of Dairy Farmers of America cooperative’s cheeses, cans of Eagle brand sweetened condensed milk, and Borden’s containers of cottage cheese, dips, and—of course—milk. Borden has made efforts to revive Elsie in the social media age. She flirted briefly with Twitter and Pinterest, and has something of a Facebook presence.

But she’s back to just being a cartoon. In the 21st century, she’s lost a bit of her dimension.

It’s too bad, because America’s food culture could use a little Elsie. Personal branding juggernauts such as Gwyneth Paltrow and Martha Stewart have the aspirational lifestyle covered, while a slew of authors, chefs, and activists including Michael Pollan, Alice Waters, and Dan Barber fight for the farm-to-table movement. But the gulf between these people and the rest of the US—and the coasts where their influences are strongest—is wide.

They all have good intentions, to be sure. But sometimes I miss the innocence of that pretty little brown cow.