Despite Beijing’s golf course moratorium, some big developers have continued to show a remarkable ability to manage and massage guanxi with local government officials. Without the right connections, it would never have been possible to operate on the grand scale needed to build a golf resort. And managing and massaging guanxi was often a very tangible business. Sources familiar with one company said that before launching a large golf course construction project in Guangdong, the developer outfitted the local police department with a new fleet of motorcycles. On Hainan island, it was said the company built the county a brand new government office building during the negotiations over another large golf-related development. That land deal fell through, but the building, or at least the shell of it, remained. “It’s sitting there like a big old white elephant,” a local source said. “That’s development in China right there.”

Most successful developers have at least one person, if not a team of three or four, whose only job is to maintain solid relationships with—if not blatantly pay off—the local officials who sign off on various aspects of development projects, regardless of the directives from Beijing. These staffers call themselves CEOs, “chief entertainment officers,” because they’re constantly picking up the tab for meals, drinks and trips to the local karaoke joint (“chief enticement officer” might be a better title). First, there’s the money that changes hands while a project is trying to get approved, and then there’s the money that changes hands while the project is trying to avoid being shut down. “It’s just to keep the trucks going, keep the villagers out of the way, secure the land,” a source said. “It’s just one thing after another.”

There was one project on the mainland where the owner didn’t play the game well with the local government, and to onlookers it was clear from early on that “the job would go on forever.” Relatively minor land issues with villagers went unresolved because the owner was “tighter than hell” and “always trying to negotiate down to nothing.” Everything with the owner “just takes forever and ever and ever,” a source said. “He will always have problems,” the person added.

Some successful developers, on the other hand, weren’t afraid to throw money at problems. They often realized that a big outlay of money now would likely save them from expensive delays later. “At the end of the day, they’re doing it the right way—for China,” a source said. “I mean, it’s just the money they’d lose by having all these people out there and delaying the project and all. You know, they’ve done it. They’ve been there. They’re the experts on it.”

Developers have been known to name a local village head as a subcontractor on critical projects. The village head makes somewhere on the order of five yuan per day for every villager he brings onto the project as a laborer, and that quickly adds up—at certain points during construction, a massive development can have thousands of local villagers on the payroll. The village head is indebted to the developer, and the developer knows it has someone who will defend the project if and when land issues arise. When disputes with villagers escalated at Haikou, one call from Mission Hills was all it took to get busloads of local officials on the scene to work things out.

Developers “know all the games to play,” one contractor said. “That’s just the China way.”

Let’s just call it leisure

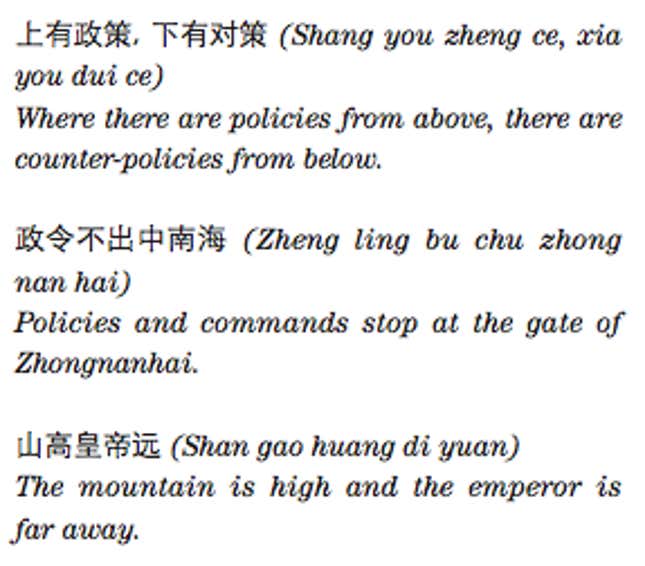

People unfamiliar with the way China works often express confusion as to how a country can experience a golf course boom during a moratorium on golf course construction. Those who’ve spent more than five minutes in China do not suffer from such confusion. In fact, the Chinese have several sayings for the disconnect that often exists between Beijing’s best intentions and how they’re interpreted—or simply ignored—out in the provinces:

Simply put, golf courses can’t be built in China without major government involvement, but that involvement is always at the local level. Indeed, local officials will often seek out golf-based real estate developments, believing them to be magnets for high-end businesses and a well-to-do clientele, not to mention major generators of tax revenue. That’s because golf isn’t taxed like a sport in China; it’s taxed as an entertainment venue, similar to a karaoke club, at a hefty 23.5% rate. In recent years, some local governments have begun offering special deals or incentives that bring this down to a more manageable rate, around 10%. One developer likened golf in China to prostitution. “That’s illegal, too,” he said. “But there are still prostitutes everywhere in this country.”

But, perhaps most importantly, local governments welcome land-hungry developments, such as those that involve golf, because they own the land. Ministry of Land Resources data and Chinese media reports in recent years suggest that anywhere between 20-50% of annual revenues enjoyed by local governments in China come from the sale of land. That doesn’t take into account the amount officials pocket on the sly, of course. “These local governments, they want money,” a contractor working in Hainan explained. “All the chiefs, all the mayors, they’re making tons of money on this stuff. Why are they not going to let it happen?”

Another golf industry professional noted that the term limits set for local government officials encouraged a sort of “race” mentality—“I’ve got three years to make as much money as I can” is common thinking among bureaucrats.

Local governments are typically willing to “fudge things” in an effort to, literally and figuratively, get the ball rolling on lucrative land development. The benefits, most reckon, outweigh the risks, even the risk that Beijing might crack down on a project that is technically illegal. But the governments are also sly. The first rule when planning a golf course in China: Don’t use the world “golf.”

“It didn’t go away—the moratorium is still there,” one industry pro reported. “People just figure out other ways to do it. No one calls it a ‘golf course’ now. It’s green space, it’s equestrian, it’s an exercise field. They are creative. But the government knows. It’s just all about loop holes.”

The government office tasked with attracting investment to a district on the outskirts of Haikou, not far from the Mission Hills site in Hainan, had learned the tricks.

One official said that, while most of the prime shoreline properties on the island had already been snatched up, they still had “plenty” of plots dominated by volcanic rock, which is useless for growing crops. Farmland and forest were off-limits to investors, but this land was available.

What if an American company wanted to build a golf course on it?

“Foreign companies can’t build golf courses,” he said. “In China, there is a restriction on golf.”

What about Mission Hills? “They are a domestic company, and they are not doing golf.”

What were they doing then? “Leisure!” he said with a wink. “Just don’t mention golf.”

To get around the restrictions, savvy developers would label their projects as “resorts.” The official explained: “Plant some flowers and trees, no problem. And maybe some people grab a club and hit a ball. That’s just leisure.” The official, tall and tanned with a relaxed demeanor, mentioned that he played golf a couple times a month.

The agreement between Mission Hills and Hainan’s Xiuying District, which administered much of the land in question for Project 791, never once used the world “golf.” The document, according to one of the first investigative stories about it, which appeared in the China Youth Daily newspaper, described a “land consolidation” project that would feature “sports and leisure,” “health facilities,” “culture and entertainment,” “leisure and business,” “international competitions,” “conferences and exhibitions,” “creative industries” and “suitable living.” The agreement suggested the project would create a “new type of tourism,” which would “improve the production and living standards of the local farmers and promote the building of a new socialist countryside.” The contract went so far as to label Project 791 as “ecological restoration.” The development, the document argued, would “improve the ecological environment” of the area, which ranged from north of Volcano Crater National Park to far south of Wang Libo’s village, Meiqiu.

Excerpted from The Forbidden Game: Golf and the Chinese Dream by Dan Washburn. Copyright © Dan Washburn 2014. Excerpted by permission of Oneworld Publications Ltd. All rights reserved.