The tragic and unexpected detail that several of the passengers lost yesterday on Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 were AIDS researchers on their way to an international conference in Melbourne is startling news, to say the least. It’s also trenchantly ironic timing. Just this past Wednesday, the United Nations AIDS program announced that new HIV infections and AIDS deaths are sharply and substantially declining. The UNAIDS program reported a 38% decline in new HIV cases since 2001, as well as a 35% decline in AIDS deaths since the death toll peaked globally in 2005.

I came of age right at the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic here in the US. My generation of gay and bisexual men, who started college in the early 1990s, was the very first wave of younger people to be fully indoctrinated under the widespread banner message of safer sex. As AIDS deaths accelerated and multiplied exponentially, inspiring countless books, films, plays, and photography exhibitions in the culture throughout my undergraduate years, HIV and AIDS were always omnipresent specters. The possibility of contracting the virus was on my mind continually when I came out during my sophomore year back in 1992, and even though I’ve always practiced safer sex, it’s never strayed very far from my thoughts since that time.

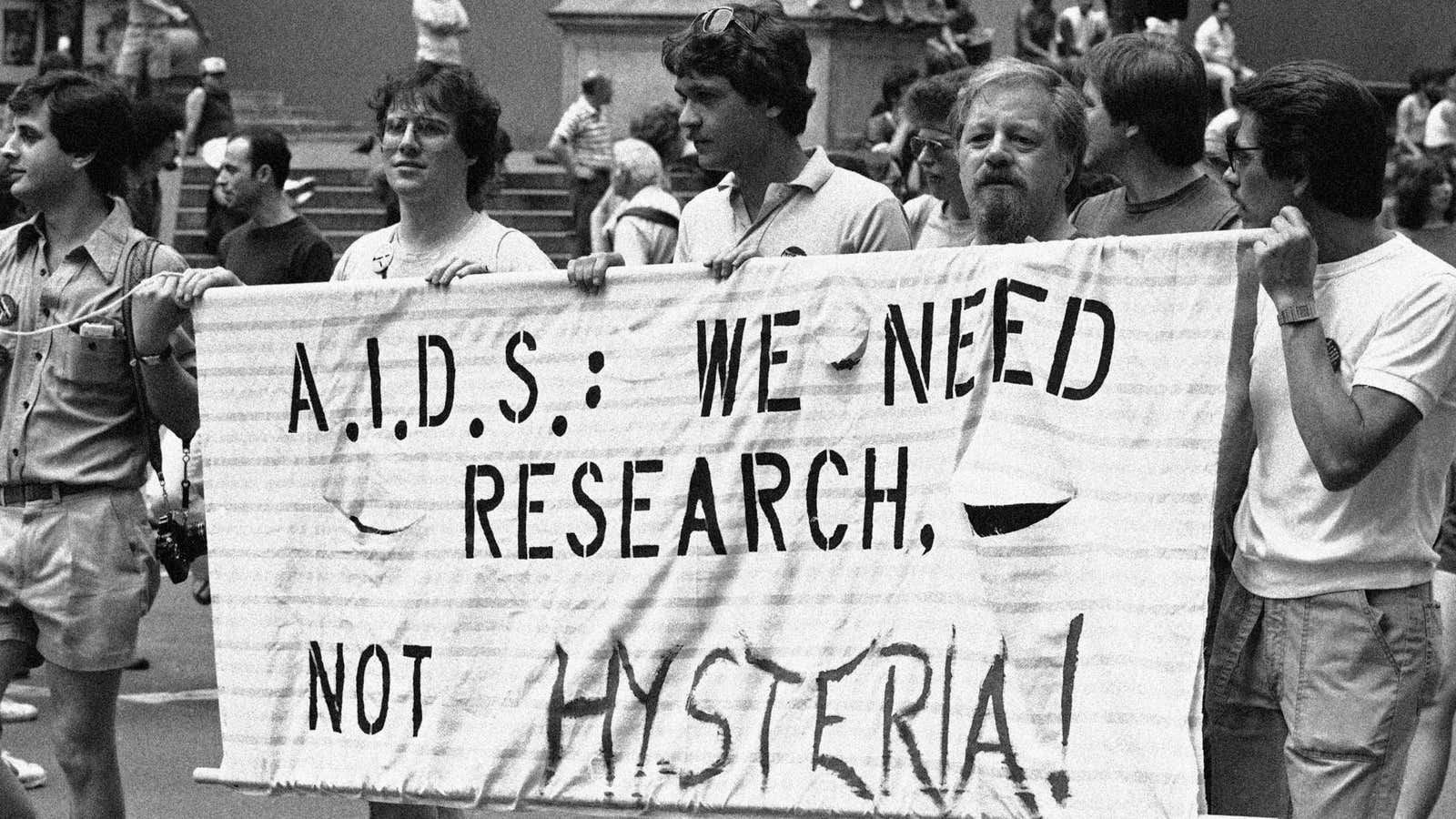

To consider the great advances of HIV/AIDS research over the past three decades is fairly mind-blowing; however, it’s just as mind-blowing to consider that there’s still no cure for the disease. In the mid-1990s, the fatality rate began to slow gradually after the introduction of the HIV “cocktail” and more effective medical treatments. Thanks to the tireless efforts of thousands of researchers and advocates like those lost yesterday on MH17, the community of gay and bisexual men that had been virtually decimated by HIV/AIDS could finally begin to recover, survive, and find hope for a future that had once seemed prematurely foreclosed to them.

My close proximity to the war-like numbers of AIDS deaths in the gay and bisexual community of that era shaped how I see the world today. Over twenty years later, those memories feel like part of a somewhat receding history to me, but with the global number of fatalities from AIDS-related complications approaching a staggering total of 40 million, the problem still feels as relevant and entrenched as ever. Currently, only one-third of the world’s 35 million people who are HIV-positive receive medical treatment for the virus. Potential preventive medications like Truvada PrEP continue to be controversial and divisive topics among gay and bisexual men.

What strikes me most is how starkly drawn the line is today between the older and younger generations of gay and bisexual men. I’m 40 now, and men who are my age and older tend to carry the burden of remembering the epidemic on their shoulders constantly, even if they’re not always consciously aware of it. For the younger generation of gay and bisexual men who grew up during a time when HIV and AIDS were, thankfully, not as often linked with queer sexuality, the association is much more remote, perhaps so distant as to seem unthreatening.

This week, the UNAIDS program predicted that with continued progress and research, it will be possible to end AIDS as soon as 2030. Nevertheless, yesterday’s tragic loss of such an important contingent of worldwide HIV/AIDS researchers and advocates on MH17 will only further hinder us from reaching the terminal point of this devastating disease.