Is it time to redraw the map of London to reflect the reality of its huge economic pull on the wider south-east? New data released last week show what an even “greater” London might look like.

Many British cities have boundaries that don’t match reality—Bristol and York for example have substantial suburbs that actually lie in neighbouring authorities. Greater Manchester is split between 10 councils, which have worked hard to overcome this administrative handicap.

London has been growing faster than any of these, and it seems reasonable to ask whether its political boundaries still make sense. We’ve done this twice before: In 1889 the London County Council was created (roughly matching today’s inner London) to recognize that the Victorian city had spread way beyond the old Roman-walled square mile. Then in 1965 the Greater London Council took in the metroland suburbs to form the capital’s current shape.

In 1965, London had a rapidly falling population. Now it is booming—with a million more people in the last decade. On top of this, a further 800,000 people commuted into London for work in 2011. That’s nearly 10% up on the previous Census, and has probably increased even further in the last three years as the recovery gathered pace.

A soaring jobs market, plus a shortage of housing, adds up to growing pressure on regional commuter rail routes to bring the workforce in from elsewhere. That’s why we need investments such as Thameslink, Crossrail 1 and Crossrail 2, to better integrate central London to the wider south-east of England.

If London’s boundaries now contain its economy so poorly, where should they be drawn? That of course is a very political question, and 50 years ago some districts fought furiously to avoid becoming part of London. But the latest Census data on travel patterns offer a good starting point.

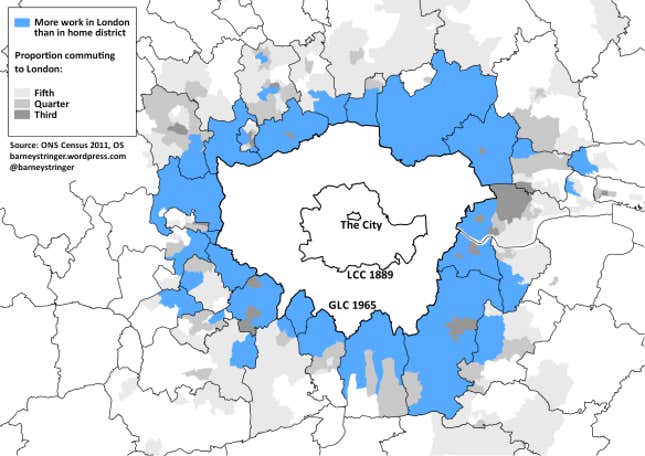

The map above shows what proportion of workers in the area around London commute into the city for work. The areas I’ve highlighted in blue are places where more people go to work in London than go to work in their own district (NB home workers are not included in these figures).

These are not so much dormitory towns, as a whole dormitory belt around London that is utterly dependent on the city for work. In many case entire districts—Epping Forest, Spelthorne, Epsom and Ewell, and Three Rivers—provide fewer jobs for their residents than London does.

More than 1.3 million people live in the area marked blue. Every day, many of them decant into London. Their council tax does not contribute toward the services they use there during the working week, nor do they get a vote on how those services should be provided.

Is it time redraw London’s boundaries once again, to embrace these areas that already function as part of the city? Or are there other ways to integrate London’s hinterland, perhaps by giving the Mayor of London greater powers over transport and housing beyond London’s boundaries?