An Australian model’s naked protest is the latest in a series of activist demonstrations against the coal mine India’s Adani group is planning to develop in Australia’s north Galilee Basin. Concerns abound about the environmental impact of the project, which involves an expansion of the Abbot Point terminal, close to the sensitive Great Barrier Reef.

While that’s what has kept the project in the news, it may be facing an even more serious challenge: its actual viability.

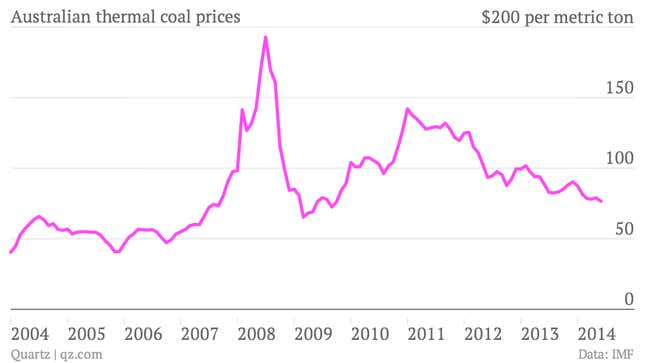

In 2010, when the Adani group, India’s largest coal importer, bought the Carmichael mine in Australia’s Queensland for $500 million, coal prices were hovering around $100 per metric ton.

Four years later, as the company now secures environmental clearances to begin its $15.5 billion project, prices have fallen to about $76 per metric ton.

That’s less than half of what the commodity cost at its peak—in 2008, it was priced at over $190 per metric ton.

And that’s also why there are doubts over whether Adani’s attempt to tap of the largest coal tenements in the world makes economic sense.

Oversupply

The main concern is that the dynamics of the global thermal coal market have changed dramatically since Adani’s purchase of Carmichael mines, Australia’s largest.

There is now more supply of thermal coal than demand worldwide, leading to a softening of prices, which are currently at a five-year-low. Demand from major consumers like China has weakened, along with increased output from major producers like Australia and Indonesia.

In effect, that means it’s probably cheaper to buy coal from the international market right now, than to extract, clean and ship it to India like Adani plans to do.

So, for the entire enterprise to make sense, Adani is likely banking on the fact that prices will recover by 2017, when it expects to start exporting the coal to India.

But Tim Buckley from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, a non-profit that backs reduction in coal dependence, reckons that by 2018 it’ll cost about $98 per ton for Carmichael coal to reach India (pdf).

Without taking transportation costs into account, the World Bank’s forecast (pdf) expects Australian coal prices to remain around $92 per ton by 2018. And after posting a compound annual growth rate of 7.1% during 2000-2013, the global demand for thermal coal imports will slow to 2.6% for 2013-2020, according to Citi Research.

“Unless you think coal prices will go through the roof,” Buckley told Quartz, “you could just buy it off the market.”

Much of this is because of a demand slowdown in China, while India, too, may exhibit “lower than expected” import appetite because of domestic constraints and currency volatility.

The slump has prompted some of the world’s largest mining companies—Anglo American, BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto—to pull out of a major port projects in Queensland, which would service the Carmichael mine among others.

“The Australian coal projects require large allied infrastructure investment and high leverage, making it challenging to achieve financial closure,” Debasish Mishra, a partner at Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu told Bloomberg earlier this year. “Some of the Indian players who have invested in Australia may be better off exiting these investment even at a loss.”

Tariffs

Moreover, to compensate producers for importing coal at such high prices, power tariffs in India—already a contentious issue—will have to significantly rise, according to Buckley’s calculations.

At a landed price of $92 per ton in 2018, the cost of power generation using this coal could be “40-90% above the Indian wholesale price of electricity of Rs 3.00-4.00/kWh and two-to-three times the PPAs (power purchase agreements) written over 2006-2009 on proposed coal-fired power plants”, Buckley said in his report.

Adani is already struggling with sustaining power projects run on imported coal due to low tariffs, and earlier this year won a compensatory increase in electricity rates.

Infrastructure

To get coal out of the Carmichael project, Adani will also have to build a 388km railway line to connect the mines in the Galilee coal basin to ports on the Queensland coast.

Apart from environmental concerns—including possible damage to the Great Barrier Reef—Adani must contend with the sheer cost of building infrastructure to support one of Australia’s largest coal mines.

Although it has got Korean major POSCO to partner in the proposed railway line, it’s unclear as to how exactly Adani plans to finance the remainder of the Carmichael venture.

But with coal prices sliding and international players exiting projects in the region, project financing could also get complicated.