We watched the Republican National convention and squirmed when Clint Eastwood talked to The Chair. We felt chills of excitement when Bill Clinton endorsed Barack Obama at the Democratic National Convention. We watched the debates. We had our own pro-life, pro-choice arguments. We can’t wait to find out if it’s Obama or Romney who will win. But today, in India, we can only wring our hands at the seemingly sudden realization that we don’t have a vote in the US presidential election.

India, especially urban and Internet-connected India, has been following the US election for the last several months. It has taken over conversation at the water cooler as well as over the dinner table. On Twitter and Facebook, we have followed what’s happening whether it is Iowa or New Hampshire very carefully. We have come to believe, in a way, that this is our election.

All morning, Indians have been declaring their votes.

“He killed Osama, my vote goes to Obama,” Hemant Nautiyal posted on his Facebook page this morning. Which is fine, except of course, that he does not get to vote. He lives in New Delhi, works in its suburb of Gurgaon, and has never even visited the US.

Nautiyal is not alone. The made-for-television (and YouTube) US electoral process has had most Indians invest far more in the selection of the US president than they have in electing their own representatives to the Parliament in New Delhi. While there is some routine discussion about how the president-elect in America will affect the Indian economy in the media, at the individual level, the interest is an emotional one.

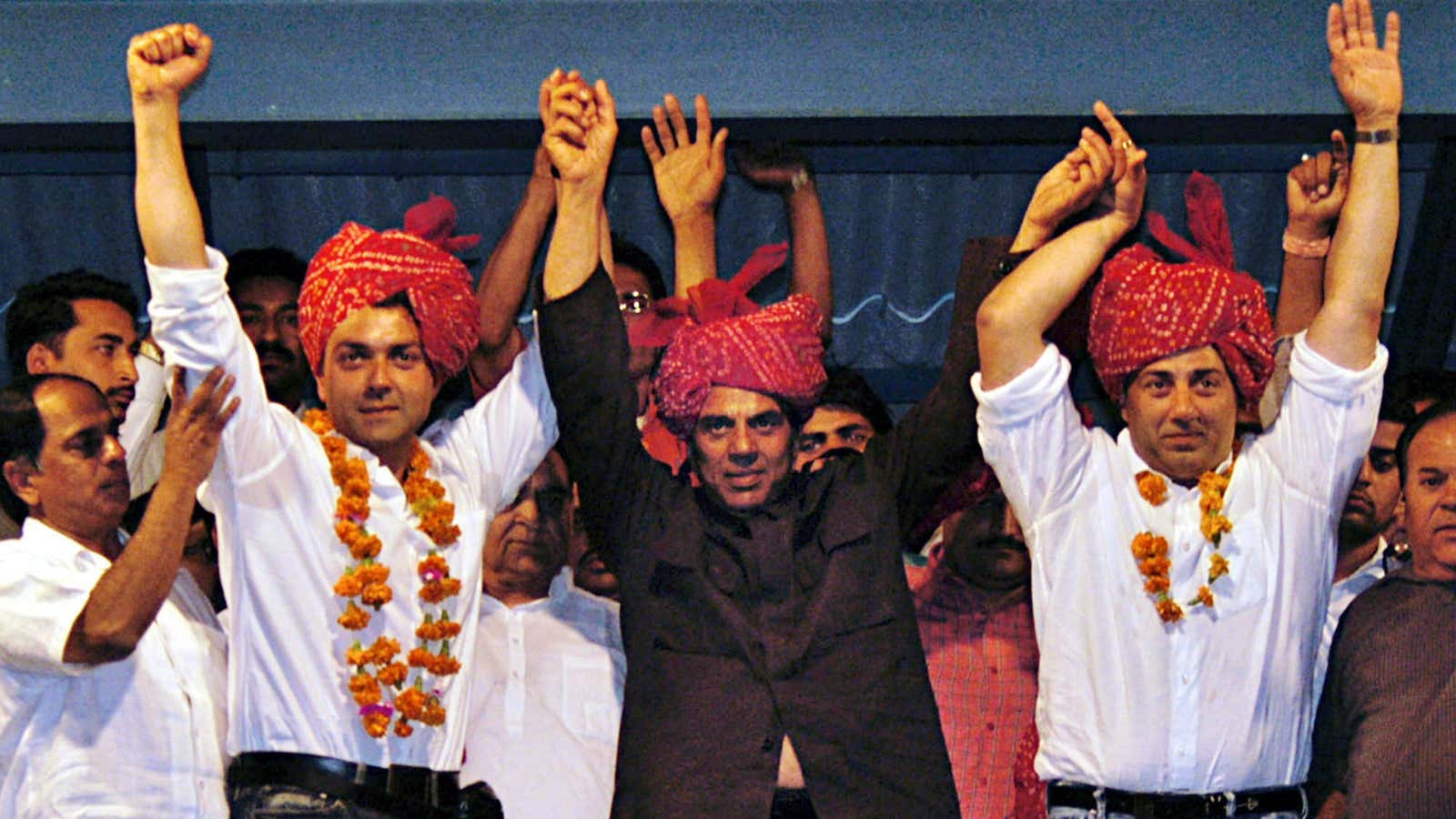

In India, elections are exciting only for the rural populace and the urban poor. The visual of Indian elections is usually that of a politician addressing a rally in the local language in a dusty town in the “other India.” The highlight of election campaigns are when semi-retired Bollywood stars are roped in and paraded through these constituencies. The election strategy of all political parties is to appeal to vote banks, large chunks of population whose votes are usually decided by their religion or their caste. Gifts are handed out, blenders to sheep.

Urban Indians are too fractured to constitute a significant vote bank and hence are often ignored by the parties. And since they see politicians as the source of the country’s problems and not its solutions, they don’t go out and vote. In 2008, after the terrorist attacks in Mumbai, there was widespread agitation against the inefficacy of the political leadership. The middle class vowed to get more involved in the political process. Yet, when elections came around, only 43% of registered voters turned up to vote.

This disconnect with the local leaders is fueling our fascination with American politics. It is ironic that when urban Indians compare India and US, we are likely to find that the American elections are conducted in a language we speak, its references are to a culture that we now know and it is the subject of discussions among the entertainers and sports people we follow.

Bruce Springsteen’s performance in support of Obama resonated with Nitish Roy, who lives in Jharkhand, a mineral-rich state which is at the center of the Maoist insurgency in India. “Why can’t elections be so good in India?” he tweeted.

He has been following the run-up to the elections carefully and predicts an Obama win. Yet, he does not have a voter identity card which is mandatory to vote in an Indian election and says even if he did have one, he is unlikely to go vote. “Everyone here has the great American dream,” he says. “That’s why we are interested in the US election. In India, there’s a scam every day, you can’t trust any politician.”

Every night on television debates, there is the usual complaining about corrupt politicians and skewed policies. Yet, when elections come around, urban India prefers to zone out and pretend like it’s happening elsewhere. Because our elections are here. In America.