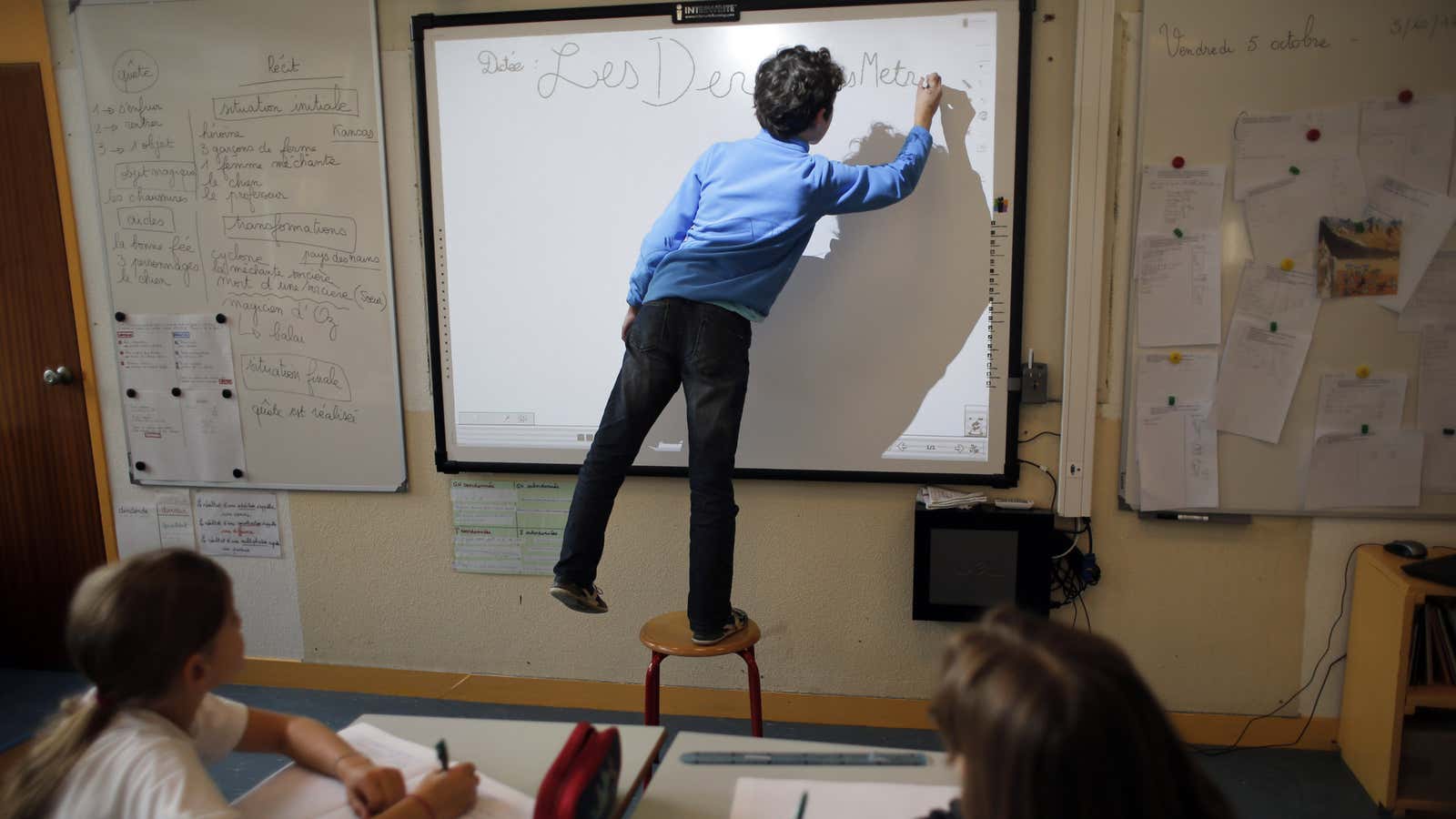

In French schools, there’s very little music or art, and virtually no sport. The baccalaureat school’s final exams, the French version of the SATs, kick off with a philosophy paper that asks questions like “Is all faith contrary to reason?” Multiple-choice questions are sneered at. There’s also no slouching or lounging around: pupils sit in straight rows in front of the teacher, and still must use fountain pens to do a lot of their class work, including math exercises. Oh, and they’re free. All the best schools in France are public ones. Or Catholic. Only rich kids who can’t keep up go to expensive private schools. Indeed, French schools look and feel very different from American ones.

But before Tiger Moms and other American educational traditionalists get too excited about the French model, it’s important to consider this: French schools have a failure rate that is high—one in five kids—and rising. Their performance on the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) tests is mediocre, behind the US in both science and reading comprehension and only just ahead in math.

So why hasn’t the French model worked? The short answer is that what’s taught in French classrooms is not particularly interesting or relevant to most pupils—including an obsessive focus on the intricacies of French grammar—and teachers haven’t been trained to bring as many students as possible up to the sought-after level. What teacher training existed in the past was mainly focused on the teachers’ own knowledge of their subject, and not on how to convey it effectively to pupils. Group work is almost nonexistent, positive reinforcement a rarity. School, ever since Napoleon, has been about producing a brilliant elite who will run the country, and to hell with the rest. That’s why France has a network of very good but very small grandes écoles, which educate the business and political leaders of tomorrow, and a lot of very bad, overcrowded universities with high dropout rates; fewer than 40% of undergraduates get their degrees in four years. And while the word égalité is inscribed on school buildings up and down the country, the correlation between school performance and household income is just as crass as it is in the US. Even in the land of good public education, the statistics show that the more affluent your family, the better your chances of academic success.

Successive French governments have wrung their hands at these growing problems, but so far they haven’t taken steps to root out the causes. That’s now starting to change. President François Hollande has made fixing French schools a major priority of his five-year term. His education minister Vincent Peillon is floating ideas and proposals (French) and already starting to implement changes.

By French standards, they’re quite radical. One reason why children are struggling, so goes the diagnosis, is because the school day is too long and stressful. Solution: change the school year to better balance out the hours, and ban homework for elementary school children. Another identified cause of the woes is a lack of teachers where it really matters. Solution: despite the financial crisis and a government-wide budgetary freeze, hire tens of thousands of new teachers (who in France are civil servants, thus almost impossible to fire). Teacher training hasn’t been effective and was largely phased out by the previous government. Solution: reintroduce and reinvent it.

Even in the land of educational pioneers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Alfred Binet (who invented IQ tests), these are controversial moves, and the debate over them is ferocious.”The minister speaks quickly, makes announcements and gives short shrift to dialog,” complained one teacher, Philippe Szykulla, in a lengthy rant in the weekly magazine Nouvel Observateur, read by many teachers.

Some groups are lobbying for more forceful attacks on the classroom culture, including less testing and the reduction or even abolition of marks in elementary school. That’s the position of the main national parents’ association, which says it is time for the government to make “some clear choices.” The association, the FCPE, also spearheaded a campaign against homework. Some go even further, demanding the baccalaureat itself to be abolished, although there’s little chance of that happening. The opponents are just as vociferous, and Peillon didn’t help his own credibility when he spoke out recently in favor of legalizing cannabis.

Do these reforms have a chance of success? Certainly, the educational establishment in France is extremely conservative and reluctant to move, and there’s no political consensus as to whether these latest reform proposals are what’s needed. But nothing focuses minds like a crisis, and the deteriorating performance of French schoolkids is undeniable. The challenge for the government will be to maintain high standards for the smartest kids at the same time as rescuing the failing ones, which is a tall order.

Peter’s book on French education, “They Shoot School Kids, Don’t They,” is available in English for digital download.