Back in 2004, Princeton was lauded for a policy attempting to reduce the steady upward march of grades at the university; it recommended that departments give no more than 35% of their students A-range grades. It may now reverse the decision after a faculty report (pdf) (endorsed by the school’s president) released on Aug. 7 found that the policy had a range of unintended, negative consequences.

Faculty will vote on the proposal this fall, and could roll back the previous standards as soon as October.

The report recommends that the numerical targets be removed, and that standards be set by departments individually. It wasn’t because it didn’t succeed in reducing grade inflation. Fewer As were awarded, and departments grew more (but certainly not entirely) aligned on grading.

But the policy only accomplished part of its goal—it failed to make grades a more accurate reflection of the quality of work.

Standards vs. quotas

According to the report, the 35% recommendation was “too often misinterpreted as quotas,” which leads to distortion, and make students feel like they’re competing for a limited number of As. It became a line in the sand instead of a benchmark, to undesirable result.

It turns out the targets might not have been necessary. A drop in grades started 2 years earlier when the faculty began to discuss the measure, even before a number was added to the mix. Simply discussing the idea made professors more aware of inflating grades.

The question the report grapples with is whether more equality in grading is always better. The conclusion was no, that putting the same standard across departments actually separated grades from performance, and didn’t account for how different departments are.

The school’s math department, for example, has big entry level courses with non math-major students that make a broad grade distribution easy. Engineering has no such courses. The result was lots of Bs or lower in introductory math courses, then much higher grades in the upper division. But grades in engineering got depressed across the board. Many grade changes didn’t seem to have much to do with the quality of work.

It often meant artificially conforming to the policy despite differences in courses or content.

The early drop in grades gave them confidence that leaving it to individual departments (albeit with oversight) could work without a cap.

As just become Bs

The aim of the policy was to increase the range of grades earned, and closer link grades to the quality of work. But in reality, it just seemed to have the effect of teachers swapping A’s for B’s.

Students who would have otherwise gotten As were simply dropped a grade, and sometimes told explicitly that it was due to the cap. That has consequences when peer institutions inflate and job applications, graduate schools, and scholarships have hard and high GPA cutoffs.

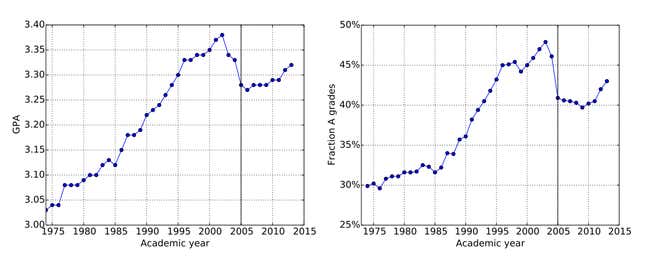

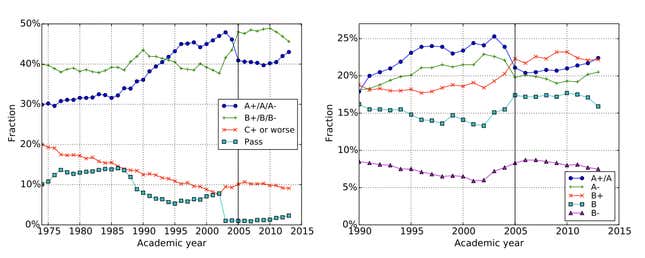

Here are chart of grade distribution before and after the 35% limit went into effect—one with all grades, the other with just just As and Bs. (In 2003, the school started recording instructor’s letter grades (but still hiding them on transcripts) on courses taken Pass/Fail.)

Unintended consequences abound

Dissatisfied students created a website that transforms a Princeton GPA into an estimate of their average had they attended inflation prone Harvard. The site estimates a 3.4 at Princeton would be a 3.56 at Harvard.

Students also cited a range of other undesirable outcomes, including questionable behavior from faculty. One student had a professor give him a paper where a score of 91 had been scratched out and replaced with an 88, and told it was because of the grade deflation policy. Another had a language professor tell the class at the beginning of the semester that only 3 of the 11 students would receive an A.

The report cited increased anxiety among students, a perception of decreased competitiveness for jobs and graduate school spots, reports that students are more anxious or less inclined to choose Princeton over another school, and a particular pressure on newly matriculated students, who usually come from a high school where they were a top performer.

And regardless of whether that’s perceived or real, one student neatly summed up the negative effect in a survey answer printed in the report:

The grading policy provides students (myself included) with an easy excuse anytime we receive grades that we don’t feel reflect our work.