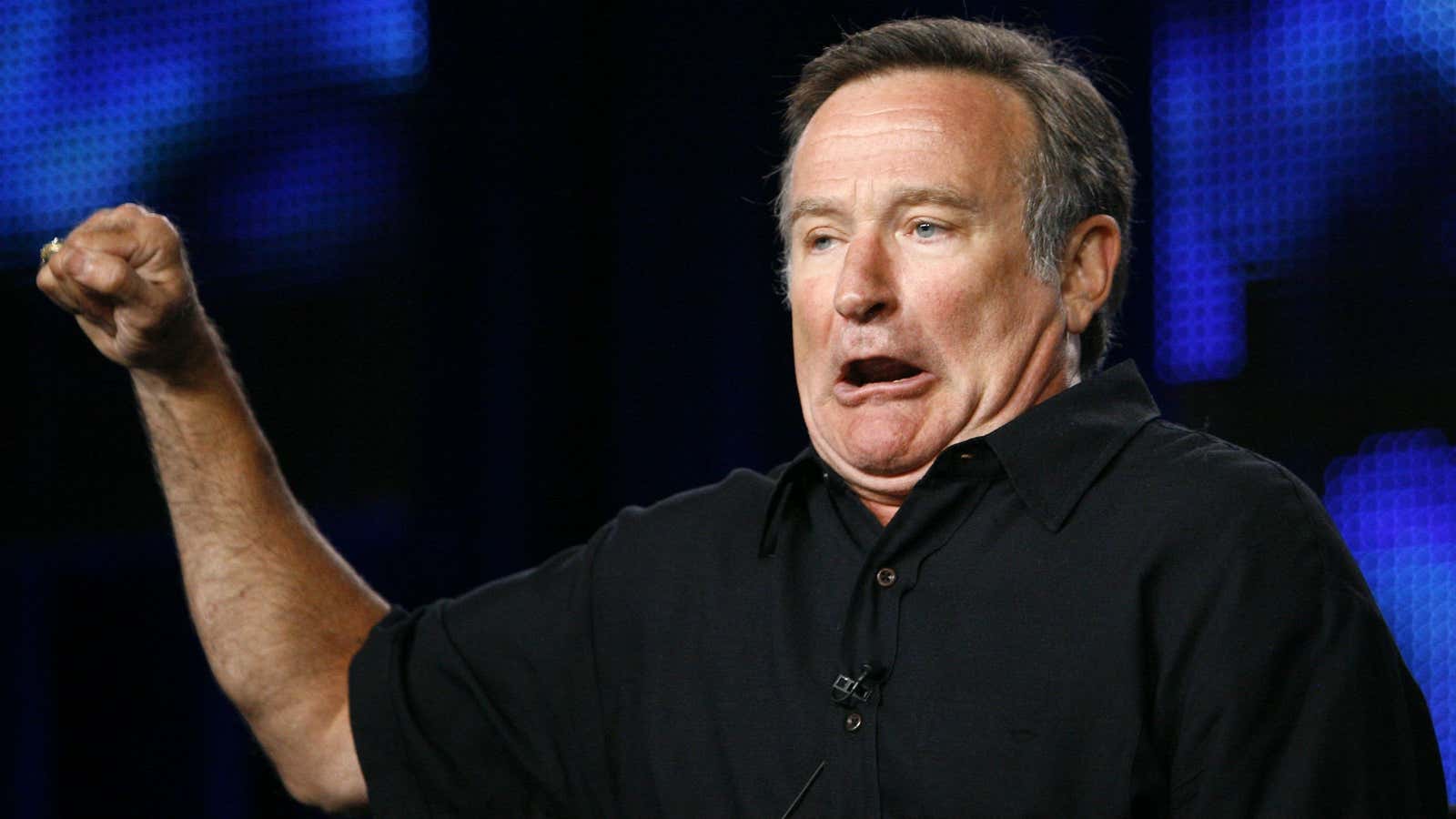

At the CBS annual upfront presentation in May 2013, as the network unveiled its upcoming fall schedule to advertisers, the most anticipated appearance on the Carnegie Hall stage was that of Robin Williams, who was returning to TV for the first time in 30 years with his new comedy The Crazy Ones. And the comedian didn’t disappoint, giving the audience their biggest laughs of upfront week with a hilarious riff that touched on partial circumcisions (don’t ask), his past cocaine addiction and all the new networks that had popped up since he was last on TV, starring in Mork & Mindy: “And if a little child wants to be transported to the Land of Make-Believe, there’s Fox News!”

It was a vintage Robin Williams stand-up performance, the type that we had taken for granted over the years. Yet the actor, who died Monday at 63 of an apparent suicide, also seemed to crack the code for career longevity in Hollywood, piecing together a deceptively nimble, rich and layered career over four decades that few other actors or comedians have been able to match. In short, he used his comedic genius as merely the foundation for a storied, and lengthy, resume.

The actor had followed a popular path to stardom: parlaying his TV success (his Happy Days character was spun off into the hugely successful 1978-1982 sitcom Mork & Mindy) into a film career that saw him become one of Hollywood’s biggest stars in films like Aladdin, Mrs. Doubtfire and The Birdcage.

But Williams wasn’t content to just coast on comedy. He honed his dramatic skills in not-just-comedic films like Good Morning, Vietnam. That led to full-fledged dramatic roles in movies like Dead Poets Society, Awakenings and 1997’s Good Will Hunting, for which he won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor. Note the word “supporting”—even then, Williams was happy to accept smaller roles and cede the spotlight to others. That certainly wasn’t something his fellow comedy superstars like Eddie Murphy, Tom Hanks, Billy Crystal and Jim Carrey were doing then—or now—with any regularity.

In the 2000s, as his star began to fade, Williams kept his career going by transitioning into meaty bad guy roles, particularly in a pair of 2002 films: Insomnia (directed by Christopher Nolan, just before he tackled the Dark Knight trilogy) and the underrated, creepy One Hour Photo. More recently, he’d been alternating leading roles in smaller films with supporting roles in larger films like the Night at the Museum trilogy, in which he played Theodore Roosevelt (the third film is due out Dec. 19).

Then last year, he brought his career full-circle, returning to TV in The Crazy Ones, as an ad agency executive. Yet again, he went in an unexpected direction, and generously ceded many of the show’s funniest lines to his costars (particularly James Wolk and Hamish Linklater). That’s not something you saw Tim Allen do when he came back to TV in Last Man Standing. But for Williams, who embraced the show’s quick transition from a star vehicle to an ensemble comedy, it was business as usual. “The pressure’s off, thank God. So I don’t have to be a Robin Williams vehicle. It’s a bus—and there’s other people on the bus!” Williams told reporters during a January on-set visit. “Now it’s a great ensemble cast. And that’s the joy for me.”

Even though Crazy Ones improved markedly during its first season, CBS canceled it in May. And now, sadly, we’ll never get the opportunity to see how Williams would have reinvented himself next: Playing a comedic anti-hero in a new series for Netflix or FX? Crushing an uproarious supporting role in the Guardians of the Galaxy sequel? Topping his Aladdin voiceover work in a Pixar film? Whatever might have come next—and as his career has shown, there definitely would have been something next—he undoubtedly would have been sensational.

While his career ended tragically, it still offers an essential lesson for his fellow actors, especially ones who no longer command the large roles and paychecks they once did: There are still plenty of opportunities to thrive in Hollywood, as long as you’re open to reinventing yourself.