Stop me if you’ve heard this story before. A grave political crisis in Baghdad threatens Iraq’s delicate ethnic and sectarian balance. The incumbent prime minister, a Shia partisan who is as obstinate as he is incompetent, clings to power. Other political parties try to dislodge him, in vain.

Then Washington and Tehran, acting separately but out of common interest, persuade the dominant Shia coalition to nominate a compromise candidate—a man with almost no public profile, no proven political or administrative skills, and no real mandate to govern. He is acceptable to the other Iraqi parties precisely for those reasons: he’s seen as weak, pliable.

We (and Iraqis) are told to judge the new man not by his lack of credibility but by his words—he talks of uniting the country, of governing on behalf of all Iraqis—and his future actions. The candidate is declared a moderate; his membership of a Shia political movement is brushed off as unimportant, as is the fact that he has received the blessing of the supreme Shia authority, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani.

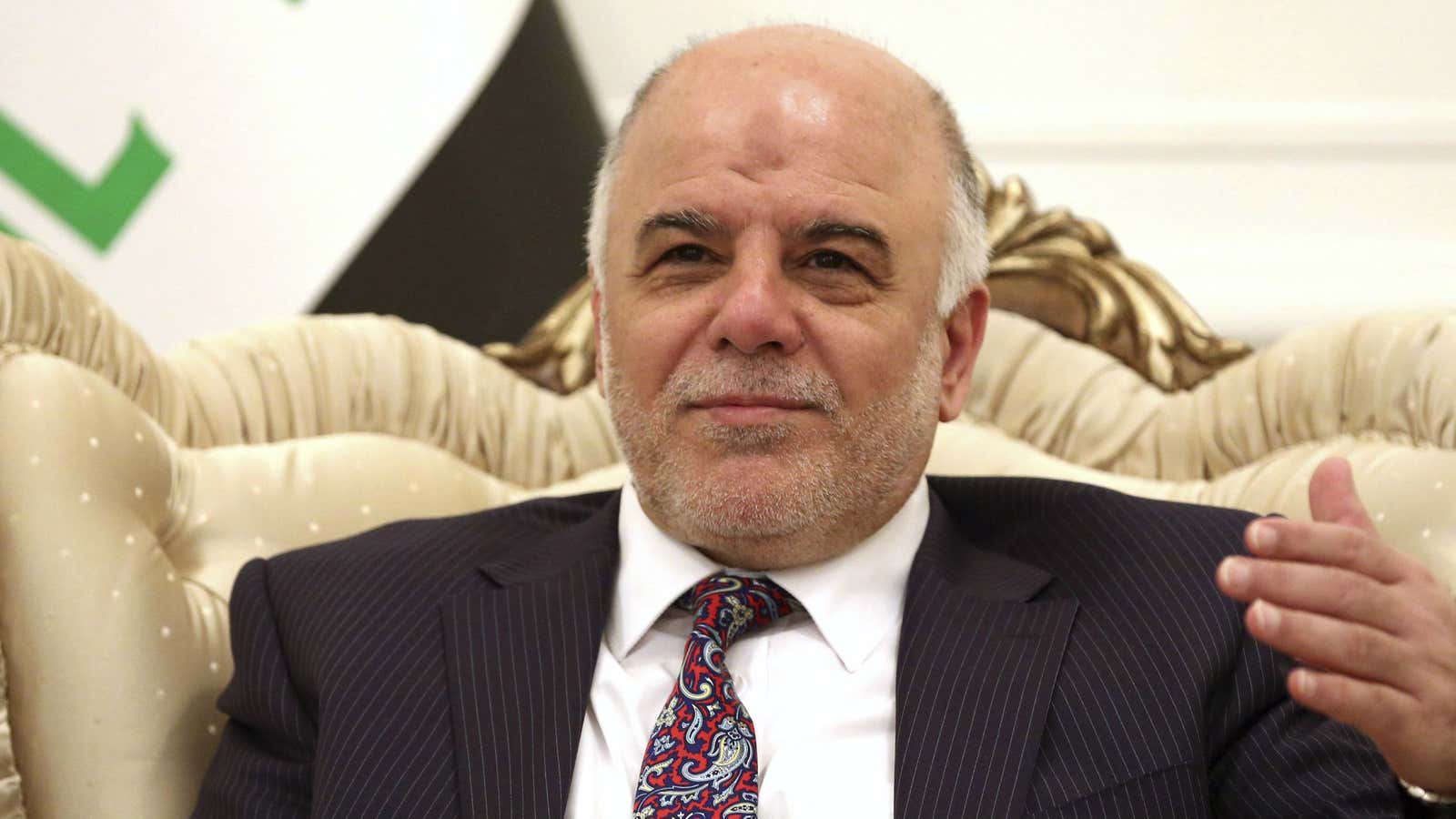

That is the story of Haider al-Abadi, soon to be Iraq’s new prime minister. That also is the story of Nouri al-Maliki, the man he is replacing.

Eight years ago, Maliki emerged from the margins of Iraqi politics as the compromise candidate to replace Ibrahim al-Jaafari (paywall)—who was, in turn, seen as a ‘soft’ choice for the top job in 2005. What else do Abadi, Maliki, and Jaafari have in common? They are all members of the Islamic Dawa, a Shia movement-turned-party. Each rose through the Dawa ranks through backroom wheeling and dealing, without having to develop any skills in retail politics.

All three were exiles for much of the Saddam Hussein era, and had ensconsed themselves in the highly-guarded Green Zone after Saddam’s fall. This meant they had little connection to the lives of the Iraqis they ruled—or, in Abadi’s case, about to rule. (Much is being made of the fact that Abadi spent a large part of his exile in the UK, as if he might have absorbed the art of parliamentary politics by osmosis. But Jaafari, too, was a Londoner.)

For the US, each man’s most compelling attribute was the fact he was not someone else: Jaafari was not Abdul Azziz al-Hakim, the Tehran-backed leader of the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq; Maliki was not Moqtada al-Sadr, the firebrand cleric and leader of the Mahdi Army militia; and now, Abadi is not Maliki. In short, the least-bad option.

For Iran, Jaafari was a failure because his incompetence threatened the survival of the Shia coalition, Tehran’s main lever of influence over Iraq. Maliki, in turn, damaged the coalition’s credibility and lost large swaths of the country to ISIL, the Sunni terrorist group that is dedicated to massacring Shia everywhere.

Jaafari and Maliki quickly proved Washington’s optimism and Tehran’s hopes misplaced. Under pressure from fellow Shia like Hakim and Sadr at home and by Iran, they pandered to the majority community, at the expense of Sunnis and Kurds. In addition to becoming openly partisan, they also presided over profoundly corrupt and inept governments. Washington backed Maliki longer than it had Jaafari, hoping he might evolve into a better leader. He did not.

Now the Obama administration is banking on Abadi to be more than a sum of his parts—a challenge beyond the ken of most politicians, anywhere.