For major companies, acquisitions are traditionally an exhaustive (and exhausting) process, requiring rigorous examination of data and the employment of a horde of well-compensated bankers and lawyers. At Google, the process comes down to co-founder Larry Page’s “toothbrush test,” according to the New York Times (paywall): Is the product the target company makes something people will use at least once a day, and that makes their lives better?

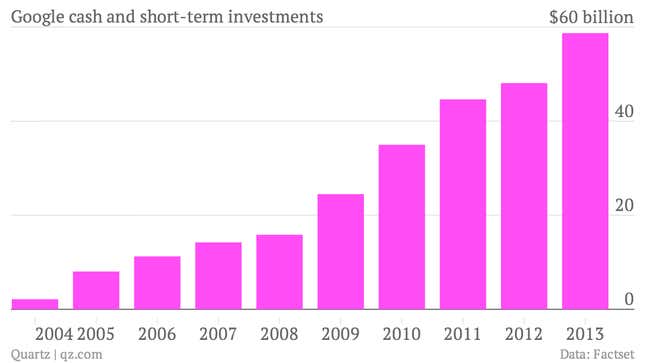

This reflects an attitude that values growth over profit, instinct and product over advice from Wall Street, and the long term over the short run. Mind you, it’s easier to take a long-term view when you have billions in revenue and cash on hand, and rapid growth, to boot:

A corporate structure where the company’s founders hold a massive amount of voting stock also helps make the decision process pretty streamlined. The dual class structure means companies can make big stock-financed acquisitions with little danger of losing any control.

Google has confronted that question several times in an aggressive acquisition spree this year, buying companies like Nest Labs, Titan Aerospace, DeepMind, Dropcam, and Songza.

And Google’s not alone. More and more, acquisition decisions in technology companies are made without advice from banks: 69% of technology acquisitions worth over $100 million this year were done without an investment bank, compared to 27% a decade ago. Apple’s buyout of Beats, and Facebook’s of Oculus were completed without the traditional advisors.

Facebook CEO Zuckerberg has a similar, product-first philosophy on acquisitions. In justifying the $19 billion his company spent to acquire messaging service WhatsApp, Zuckerberg pointed out that that it was on a path to reach a billion people, and that there are very few services that do so. Scale and uniqueness matter more than getting the best possible deal or most seamless integration.

This is a clear contrast with the rest of the corporate world, where deals are often as much about financial engineering as they are about adding complementary services or products. Instead of relying on banks, tech companies are building their own acquisition teams. So not only are tech companies avoiding the investment banks, they’re looking to poach banking stars.