The unrest in Ferguson, Missouri continues to escalate. Yet here in New York City, America’s largest by population, it’s been more two decades since we’ve seen any serious rioting.

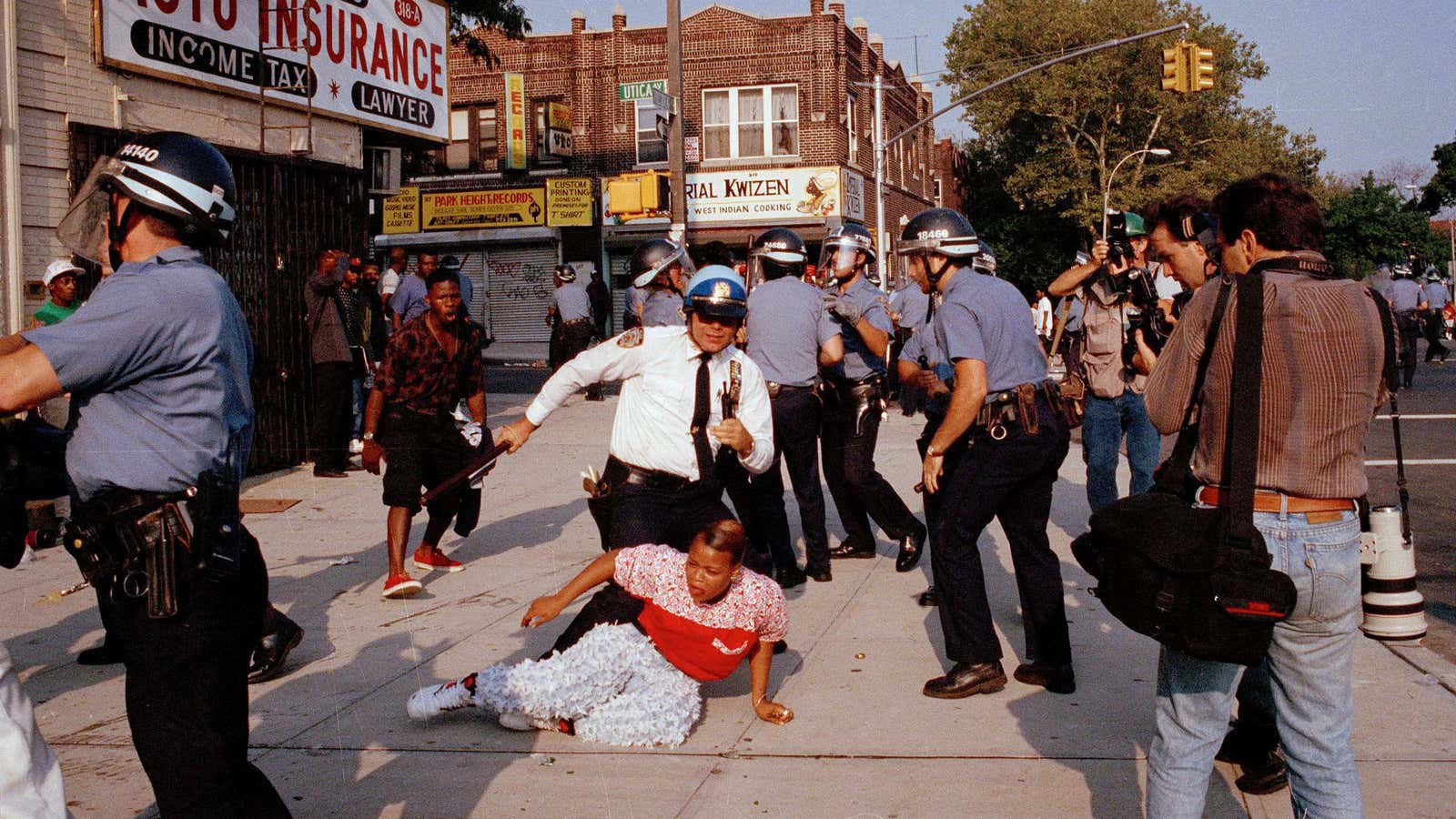

The Big Apple hasn’t really seen the scale of such protests as what is unfolding in Ferguson since the three-day Crown Heights riots of 1991 (the effect of Hasidic-black tensions and an NYPD slow to react). There was also, to a lesser extent, the Washington Heights riot of 1993 (the result of the fatal police shooting of a minor drug dealer named Kiko Garcia). Of course there have been lesser flareups—the 1998 march in memory of Matthew Shepard, a young gay man murdered in Wyoming, the protests of the 2004 Republican National Convention (largely white demonstrators herded into a toxic garage), Ray Kelly’s over-self-indulgent crackdowns on the Critical Mass bicycle rides, the modest unrest at the Biggie Smalls funeral, the Occupy Wall Street demonstrations.

And yet nothing like the looting, arrests, and tear gas halfway across the country.

Even in our polyglot city of more than 8 million people, it seems almost absurd that the National Guard would be called into the streets to blunt violent demonstrations. And it seems equally absurd that folks would torch businesses in their own neighborhoods even to protest the death of one of their own. That’s not to say New York City has somehow escaped the racial tension that has come to define Ferguson. Indeed, New York’s many neighborhoods are divided among racial and ethnic lines and its public schools are the most segregated in the nation, according to a report released in March by the UCLA Civil Rights Project.

One explanation may be that the New York Police Department—the largest and most well-funded police force in the United States—has refined its crowd- control techniques over the past two decades. Police respond rapidly to any crowd gathering and have a whole unit known as ”Community Affairs” officers to calm emotions. The use of interlocking metal “pens” to separate protesters and break groups of them into boxes may result in injuries at times, but it does not allow that “critical mass” to develop in demonstrations.

Another factor is that the NYPD even at its currently reduced ranks of about 34,000—compared to more than 40,000 a decade ago—is still large enough to act as more of a deterrent to rioting than any National Guard. It seems fairly clear that New Yorkers would rather be pushed around by their own police than a uniformed group of outsiders acting under state or federal mandate.

That’s not to say New York hasn’t had its share of controversial police fatalities as any other city in the country. In 2012, the last year for which statistics are available, the NYPD shot and killed 16 people, the highest number in 14 years.

Consider the case of African immigrant Amadou Diallo, killed in February 1999. In Ferguson, Michael Brown was shot six times, according to an autopsy released earlier this week. Diallo was shot 19 times. The NYPD officers fired a total of 41 shots at him. Unlike Brown, allegedly asked to stop walking in the middle of the street, Diallo wasn’t even remotely a suspect in any wrongdoing or crime. He was coming home from his job selling DVDs on 14th Street, was unarmed and was merely holding his wallet when approached by overzealous plainclothes officers from the Street Crime Unit. While there certainly a great deal of anger and there certainly were demonstrations here following his killing, none remotely approached civil unrest.

Similarly, Nicholas Heyward Jr., only 13, was shot and killed in 1994 by an officer who mistook his toy gun for the real thing. Even after then Brooklyn district attorney Charles Hynes declined to press charges against the officer, there was no rioting.

And then there was Ernest Sayon. He was suffocated to death by police in Staten Island in 1994, in a very similar fashion to the chokehold death of Eric Garner in Staten Island last month. Once again, in both cases, demonstrations ensued, but no unrest.

The fatal shooting of Sean Bell by police in Queens in 2006 led to protests and a great deal of anger. But still no unrest, despite many a tabloid speculating it was likely. Even after the officers involved were acquitted, relative calm prevailed. This is a marked different story from when the Los Angeles police officers who beat Rodney King were themselves acquitted.

It forces the question of why rioting erupted in Ferguson, a town of just 21,203 people, when the supposedly much more volcanic New York has been spared for two decades. One might point to a history of racial tension in Ferguson and a 53-officer police department that is almost all white. (The NYPD is about half white.) But really a confluence of factors appear at work. Chiefly in Ferguson, there was a failure by law enforcement to react quickly and thoughtfully, and then a clear overreaction with military gear and vehicles. Sending in the state police seemed to calm the problem for a day, but that just wasn’t enough.

Perhaps what’s happening in Ferguson could replicate itself here, given the right circumstances. What those circumstances might be, as someone who has covered the NYPD since 1993, I couldn’t hazard a guess. Of course, even if I were to guess, that might be hazardous.