In 2008, after Barack Obama was declared the next US president, I called my niece Sadie. It was her ninth birthday, sure, but I also needed a buffer from a rush of emotions. Like Obama, I have a black father and a white mother from Kansas. I had taken a leave of absence from my job at Google to campaign in Ohio. Four weeks, 18-hour days, thousands of conversations with voters built up to that one phone call.

So easily, my ploy failed. I cried.

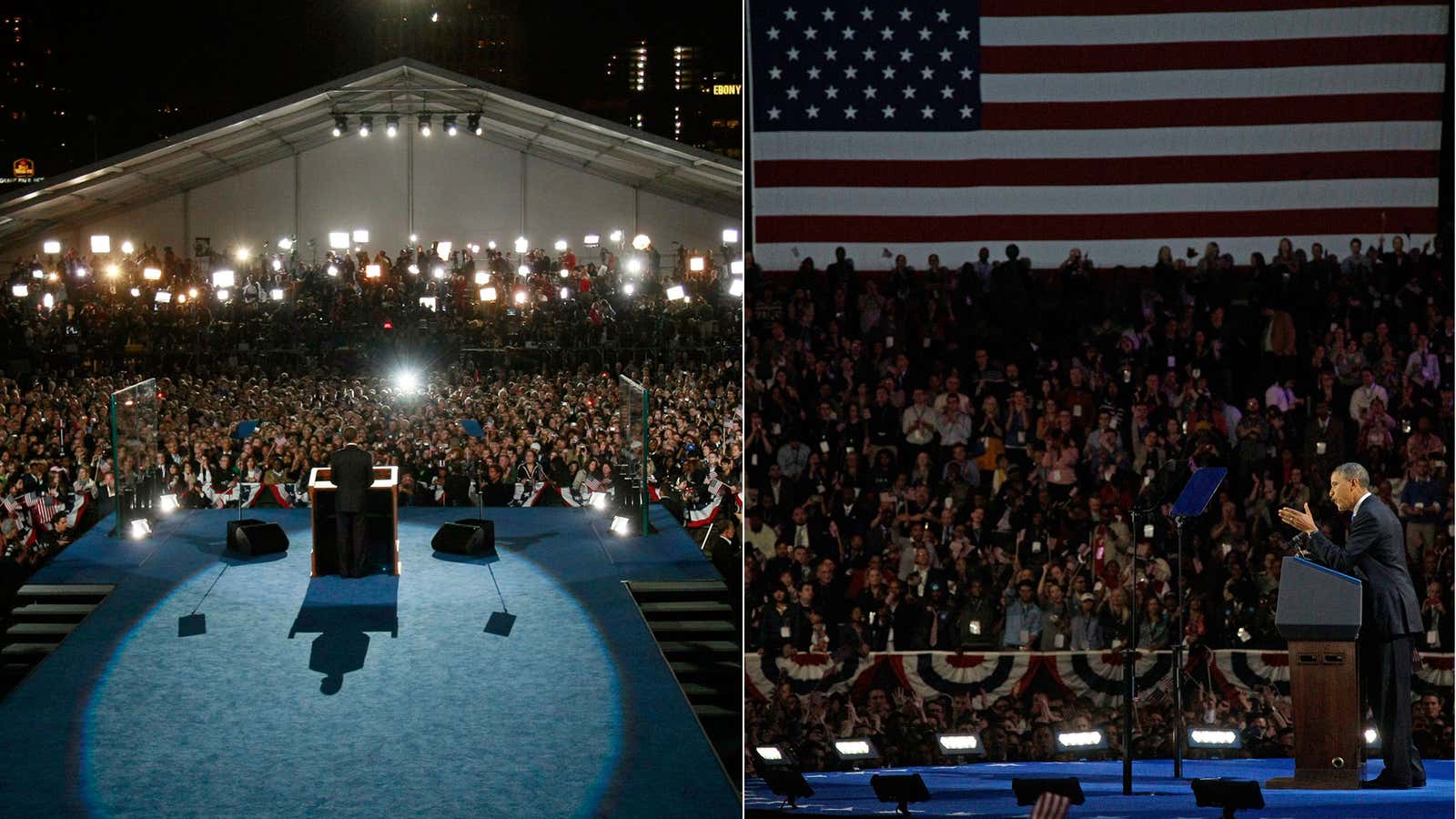

I was hardly alone. For millions of people around the country and around the world, hopes and emotions ran high around the election of the first black president. November 4, 2008 was even shown scientifically to be one of the happiest days in years.

Four years later, I stayed home. I’m still at Google, but I’m older now and it’s harder to just take a month off life and work.

Last night, those hopeful, emotional days in Ohio felt long gone. Heading into the 2012 election, I was more concerned that Obama’s legislative achievements, including his healthcare plan (the Affordable Care Act, or ACA), would stay on track than I was with the history of reelecting the president. When Pennsylvania was called for Obama, I fist-pumped in the name of healthcare. With New Hampshire, too, I high-fived in the name of the Dodd-Frank reforms of Wall Street. My conversion to policy wonk was official.

But then Ohio was again called for Obama. He’d done it again, as easily as the last time. Only then, the significance of this second election of the nation’s first black president snapped into focus.

The 2012 election is not only about cementing healthcare reform and the hope for other transformational legislative pursuits (like an overhaul of immigration). It is a continuation of that journey we began in 2008, an affirmation of what the president represents—a multicultural America striving for progress through cooperation. As a columnist for The Root describes, the politicos will now shift to match this America, where women, blacks, Latinos, and gays exert significant influence over the political agenda.

Indeed, my upbringing guided me to the Obama campaign. Growing up in constant reverence to the civil rights movement—my parents named me after Andrew Young and Martin Luther King Jr.—I understood the historical heft of electing the first black president. I mentally dusted off the spot on the wall next to my parents’ living room paintings of Malcolm X and Nelson Mandela, hoping to place one of Barack Obama there.

While studying at Northwestern University, outside Chicago, I watched the ascension of Obama from state senator to US senator. After he spoke at my graduation, I considered campaigning for the first time. In September 2007, I attended “Camp Obama,” an organizing training camp for volunteers run by Harvard professor, Marshall Ganz. I cared deeply for the then-candidate’s belief that access to quality healthcare was a human right. I supported his determination to end our two wars. But given our shared backgrounds, my devotion was hardly political alone. For the first time, I found a candidate that I recognized behind the podium. Our similarities are not only racial: I also used student loans to get through school. And we both think we’re better at pick-up basketball than we really are.

After volunteering in California, Nevada, and Texas, I landed in a staff position in Cleveland, Ohio, with four weeks to go in the 2008 election. I must have worn out my shoes walking the city’s poorer east side during my first two weeks. Sometimes, the backdrop was largely familiar and normal: sunny days, neighbors out talking, a father and child playing with a remote-controlled car in a driveway. But everyday came the reminders; I passed rows of what felt like the same boarded-up two-story house. Cleveland had been struck by a most unnatural disaster, an economic hurricane with no relief in sight.

Barack Obama promised hope, when Cleveland most needed it. Not only were some residents dealing with the near collapse of their communities but they were also suffering from a history of voter suppression and intimidation. That city helped send Obama to the White House. And again last night, Cleveland played its part in pushing our new public narrative forward.

2008 was not just one historic moment. But when combined with this 2012 election, the result is a cosmic shift in our public narrative. And that narrative seems more likely to accelerate than stall. Not only did last night give us the most female US senators ever with 19, but we also have our first openly gay senator, Tammy Baldwin of Wisconsin. I predict these new records, 19 and 1, will be broken soon. I also don’t think anyone would bet against a native Spanish speaker landing in the White House within the next 20 years. The tangible possibility alone is a huge victory. More diverse legislative representation helps ensure smarter policies on issues that perpetually dog us: immigration reform, climate change, debt and inequality.

It’s also important to remember how 2008 and the White House’s subsequent achievements influenced this election’s outcome. Early voting tactics pioneered in 2008 battleground states, for example, helped propel the president to victory. And his advocacy of gay rights throughout the first term set the table for Minnesota to become the first state to defeat a constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage.

Last night, I called my niece again. Sadie had been a teenager for all of two days. When I nervously chatted away about returns in battleground states, she told me it was “obvious” Obama was going to win and hung up. She then sent a mass text message (saying “Go Obama!”) and went to sleep before Ohio was called. Sadie woke up today in a country where the leaders behind the podiums now look a little bit more like her. That’s going to be the norm now in this new America, but it’s nothing to take for granted.