How Russia can hurt the West: An embargo hit list for Vladimir Putin

Sanctions are a blunt tool. Their effects can be unpredictable, for the target of an embargo as well as the side that imposes it.

Sanctions are a blunt tool. Their effects can be unpredictable, for the target of an embargo as well as the side that imposes it.

As the tensions between Russia and West show few signs of de-escalation—quite the opposite, in fact—the risks of a sanctions spiral are rising. So far, in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its support for the separatists in Eastern Ukraine, the US, EU, and others have slapped travel bans and asset freezes on a host of prominent officials and imposed broader restrictions on Russia’s finance, energy, and defense sectors.

The effects have ranged from the grounding of an oligarch’s private jet to Russia’s largest oil company begging the Kremlin for a $42 billion loan to replace lost sources of funds.

For its part, Russia has retaliated by restricting what it buys, rather than what it sells. Russia’s exports are dominated by oil and gas, and stopping these sales would blow a huge hole in its budget. It has instead banned food imports from the US, EU, Norway, Canada, and Australia.

This is squeezing French peach growers and Finnish dairy farmers, and in an unwelcome and unexpected headache for the European Central Bank, it is also pushing the euro zone closer to deflation.

Moscow’s next move could be to ban car imports. Russia imported more than $10 billion in passenger cars from the US and EU last year, or around 60% of its total auto imports. Foreign-made cars account for around 30% of all sales in Russia, so this move wouldn’t go unnoticed by local motorists.

Meanwhile, exports to Russia account for only around 3% of American and European car exports.

Are there better things—from the Kremlin’s point of view—to ban instead? Ideally, an import embargo hurts the targeted trade partners more than local consumers. With this in mind, Quartz scoured trade data for trade categories where Russia relies less on imports from the countries it is feuding with than they rely on exports to Russia.

Tellingly, there are no obvious targets. In just about every category of any real significance—aside from energy—Russia needs the West more than the West needs Russia. But there are a few areas where Russia could hurt a country’s exporters at least as much as, if not more than, it hampers its own imports. And although the German wallpaper and Norwegian fish-fodder industries may not be as powerful as the farm and auto lobbies, Moscow will be looking to exert pressure on its enemies wherever it can.

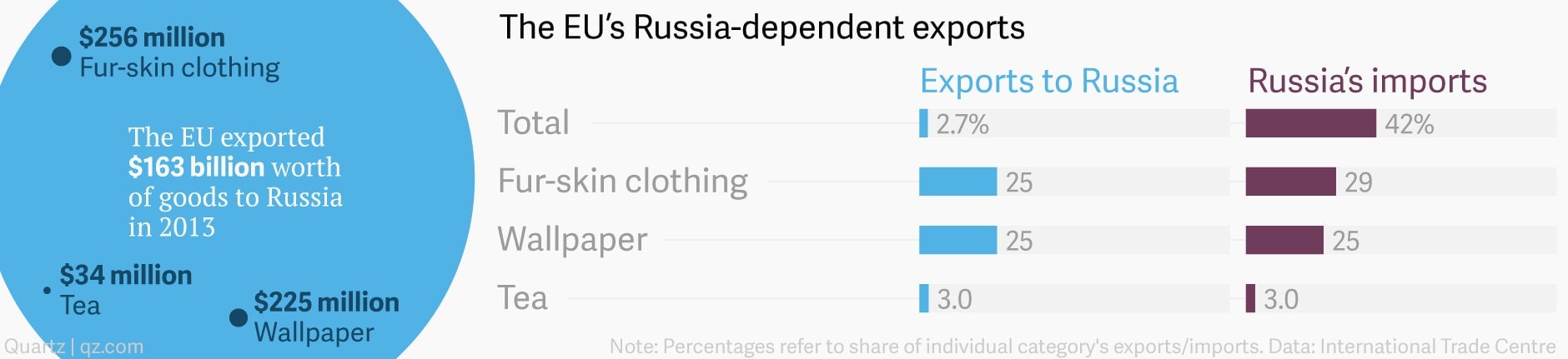

European Union

Since the EU is acting as a bloc when it comes to Russian sanctions, Moscow can’t pick on individual member states in crafting an embargo. Given that the EU economy is more than eight times bigger than Russia’s, it’s nearly impossible to find any obvious imports where a Russian embargo would hurt the EU more than Russia would hurt itself. The best Moscow can do is inflict roughly equal damage on the EU’s exports as it does on its own imports.

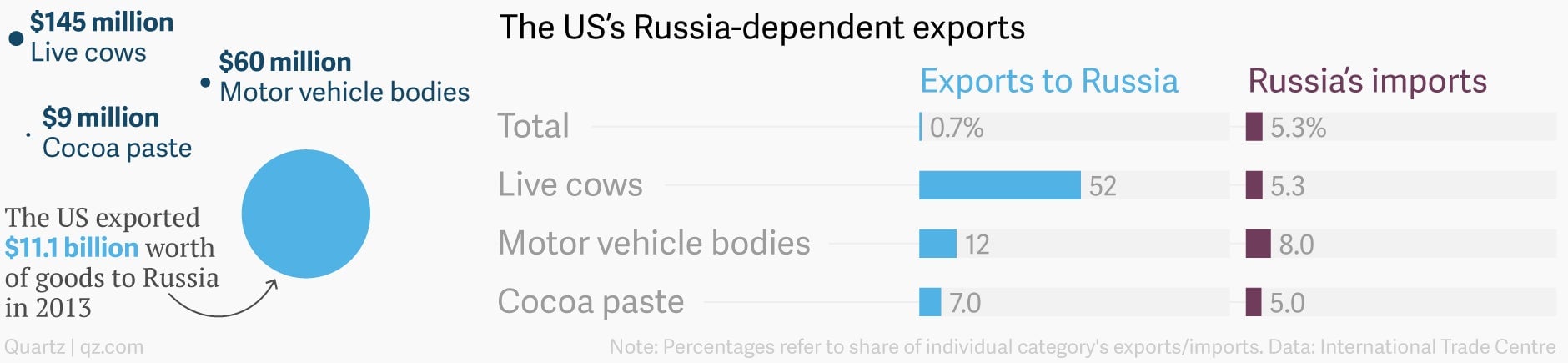

United States

Less than 1% of US exports go to Russia, so there isn’t much an embargo can do to stick it to the Americans. This is also why some of the sharpest rhetoric in the war of words between Russia and the West has come from Washington.

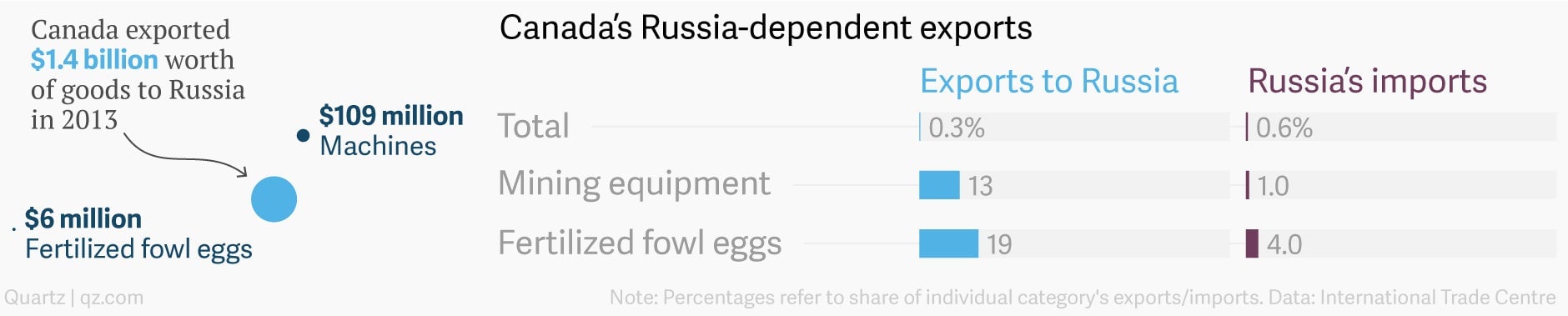

Canada

Russia’s food ban already did a fair bit of damage to Canada—meat and fish are the second- and fourth-largest Canadian exports to Russia, worth more than $350 million last year. A ban on some mining machinery could impose additional pain, but in the grand scheme of things Russian trade is a rounding error for Canada.

Australia

Meat and dairy exports account for more than half of Australia’s exports to Russia, so the damage here has been done. There is little economic ammunition left for Moscow to do much any meaningful harm to Australia.

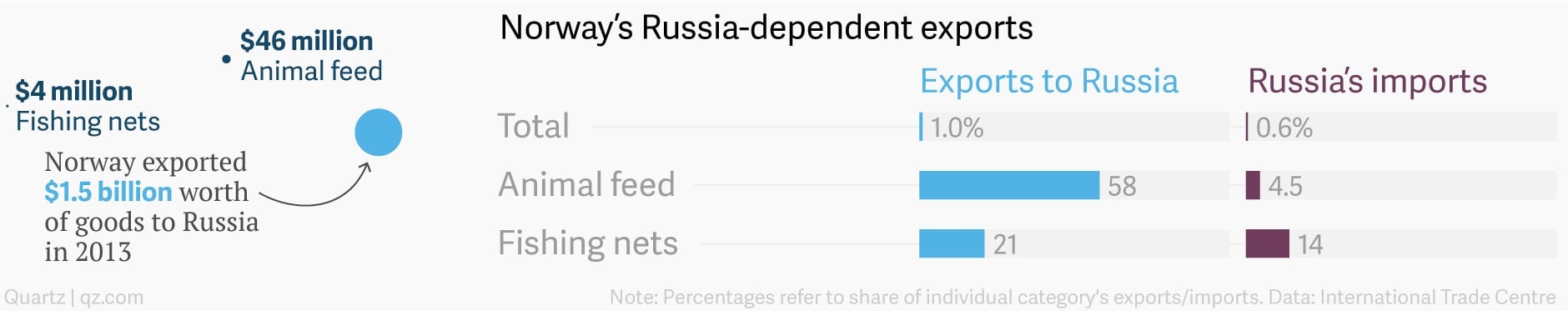

Norway

At a stroke, Russia’s food ban blocked three-quarters of Norway’s exports, comprised almost entirely of fish. There are a few fishing-related items not covered by the ban that Russia could restrict, but Norway’s oil-backed economy will hardly notice.