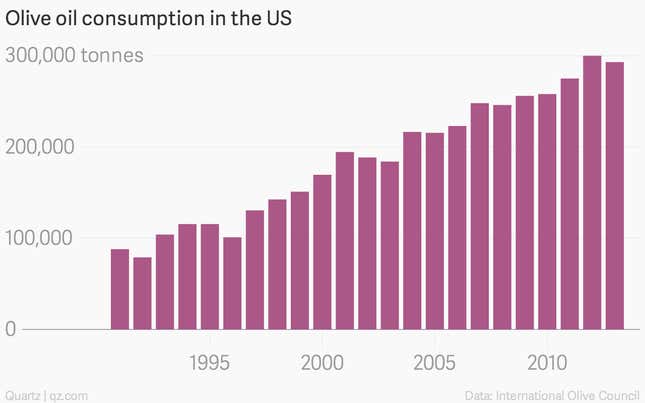

American consumption of olive oil has been rising steadily for decades, especially since consumers have become informed about the benefits of Mediterranean-inspired diets. Swapping olive oil for butter is widely recognized as a way to make various snacks and meals healthier; the oil has no cholesterol, is high in monounsaturated fat, and contains antioxidants. Olive oil also beats other traditional cooking oils (such as soybean, palm, and peanut oils) on many of those points, and in this regard, too: only the Mediterranean’s “liquid gold” has been linked to lowering the risk of diseases from breast cancer to Alzheimer’s.

No wonder the worldwide olive oil market is worth $11 billion. And while global production of the stuff has more than doubled since 1990, from 1.5 million metric tons (tonnes) to over 3 million, US imports of it have tripled.

A recent study by agricultural economists at the University of California, Davis, suggests that America’s love affair with olive oil has arrived at a turning point. The US has always imported most of its olive oil from Italy and Spain; imports from Greece, Morocco, Tunisia, and Turkey have helped meet the rising demand. Now, though, American enthusiasm for olive oil is so great that the US is uniquely positioned to change the future of the global olive oil industry—perhaps by encouraging competition from other countries such as Australia, Argentina, and Chile, and perhaps by emerging as a competing producer itself.

With olive crops in Spain and Italy occasionally subject to drought and bacterial infections, it can’t hurt to diversify the world’s sources of high-quality, unadulterated virgin oil. The question is whether Americans can be convinced to buy domestic varieties instead of foreign ones.

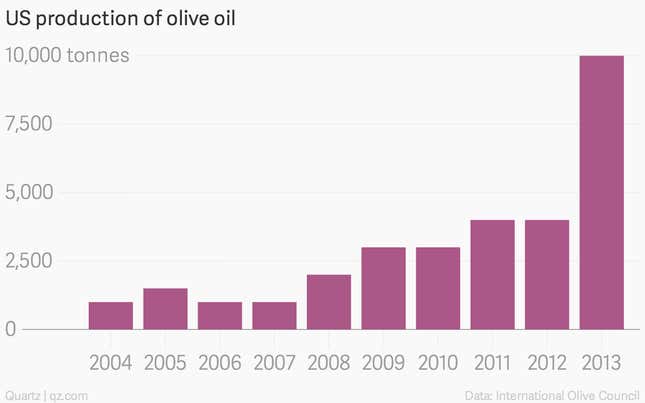

There hasn’t been much opportunity to test the market—in 2012, US producers contributed about 4,000 metric tons to the market, less than 2% of all the olive oil sold in the country that year. In 2013, though, according to the International Olive Council, US production surged to 10,000 tonnes. And domestic producers, especially those in California, have begun campaigning to gain acceptance in a market that overwhelmingly, and perhaps irrationally, favors imported varieties.

Food Network star Rachael Ray made extra-virgin olive oil a darling of American foodies when she started calling it “EVOO” and dispensing it liberally on her cooking show in the mid-2000’s; today, the 40% of US consumers that buy olive oil tend to favor extra-virgin varieties over others (pdf). They also gravitate toward labels with Italian flags on them. Beyond those markers, the average American doesn’t know what truly distinguishes high-end olive oil.

It’s hard to blame them for this, because determining quality isn’t just a matter of reading the labels on bottles at the supermarket. As author Tom Mueller has investigated at length, olive-oil fraud is rampant in Europe, and perhaps half of the bottles that appear to be “extra-virgin” and “from Italy” are neither.

This is the charge the US olive growers are using to make their case. They argue that the US government should impose stricter standards on imports, so that their legitimately pure, American-made oil doesn’t have to compete with rancid, soybean-tainted European stuff masquerading as the real thing. Producers in northern and central California, like California Olive Ranch, see themselves on the cusp of a coming-out not unlike the one the California wine industry experienced in the 1970s.

At Stonehouse Olive Oil in San Francisco, which calls itself “part of the farmer’s market revolution in the United States,” customers are encouraged to sample everything inside the company’s flagship store. The manager there, Linda Daniels, tells Quartz the strategy is “all about creating the ambience and the experience for people to taste.” Once they do, “they realize the difference between this and what they’ve been buying,” which generally is imported.

Given the response from customers and the significance of two other trends in the food business now, Daniels is optimistic about the future of California’s olive oil industry. “You can’t get more fresh or more local,” she told Quartz on the phone last Friday, in between helping customers at the busy-sounding store, which is open seven days a week.

Olive growers in California, Texas, and other US states have the knowledge and the technology to produce olive oil that’s “at least as good” as the finest in Europe, says Dan Sumner, one of the authors of the UC-Davis study. He notes the importance of associating food with stories and experiences—a tactic that artisan producers such as Stonehouse can easily employ locally. But he doesn’t see US oil makers being limited to this niche; he says domestic producers should be able to hit all segments of the market, supplying olive oil commercially both to restaurants and food manufacturers, and at retail, whether appealing to sophisticated customers of high-end, independent food markets or appearing on shelves at chain grocery stores.

What it may take for the domestic olive oil industry to really hit its stride is simply more PR. One of the most interesting aspects of the UC-Davis study noted the impact that media coverage of olive oil has had on consumer demand:

We find that news articles about the healthiness or culinary benefits of olive oil contribute significantly to U.S. rising demand for olive oils… We also find that news reports promote the U.S. demand for EU virgin oils more than that for other oils. Given the stock of articles and the value of U.S. import of olive oils as of 2012, 100 more articles on the health or culinary benefits of olive oil would increase the value of U.S. annual import of olive oils by about $1.6 million in the long run.

So the California Olive Council would benefit, probably, from more articles like this one.

For the record, The New Yorker has been and continues to be an excellent source of news articles on the business of olive oil. Mueller’s original reporting on “the dark side“ of the business appeared there in 2007, and a “Talk of the Town” piece from Aug. 3, 1946 (paywall) provides lasting and valuable information about the industry as a whole:

In addition to being the best base for salad dressings, olive oil is taken internally by employees of lead factories to prevent absorption of lead and is an ingredient of liniments and soap. The bulk of it, however, is bought by people of Latin extraction, who use it as benighted northern Europeans and their descendants use butter and other fats—for frying eggs, fish, and so on. One explanation may be that butter doesn’t keep well in hot climates, whereas olive oil is unaffected by high temperatures; another is that olive trees flourish in dry, rocky countries, and cows don’t. In any event, trafficking in olive oil is now several thousand years old and has won suitable recognition in art and literature as well as in cooking.

… For centuries, Spain has been the biggest olive-oil producer, and the Spanish people consume 87,000,000 gallons a year, when they can get it. Ninety-three per cent of the world olive crop is used for oil, the rest being pickled and canned. The first pressing of the olives produces what is known as virgin oil, the second pressing corriente, or current, oil. Virgin oil is light in color and palatable; corriente is dark and bitter. An important Italian industry is the refining and blending of these two oils to arrive at a uniform product, a process which, despite the difference in outcome, somewhat resembles the production of whiskey. Much of the inexpensive olive oil in this country is adulterated, the average American being unable to detect any variation in taste between real and fake oil.