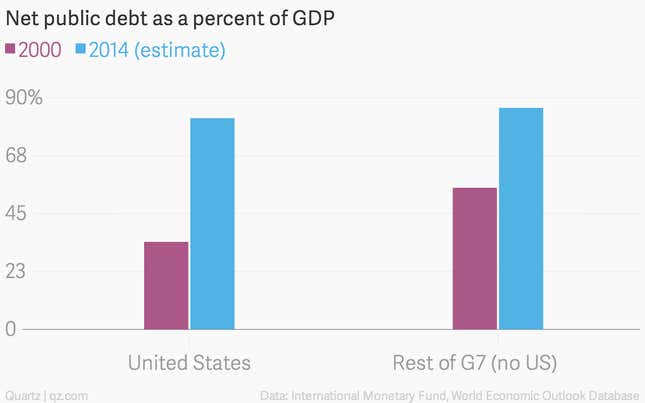

On matters of fiscal health, the US has not traditionally looked to Europe for guidance. For much of the past three decades, governments in Italy, France, and Germany were much deeper in the hole than the US.

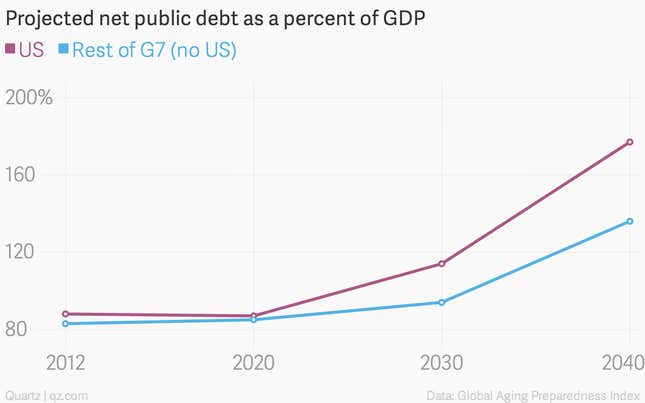

How things have changed. The US racked up debt faster than any other G7 country during the Great Recession, so that its debt burden is now as bad as the average European country. If current projections hold, by 2040 the US will have the worst debt burden of any G7 country save for Japan, reaching levels not seen since World War II.

There are real costs to so much debt. More public dollars are consumed by interest payments instead of paying for defense or other public services. And when the economy begins to recover more strongly, interest rates will rise from their recent historic lows, creating a much heavier burden.

All advanced countries have faced similar challenges in controlling government debt and most have made austerity cuts that have slowed economic growth and employment in the short term. But, surprisingly, Europe—despite facing more difficult decisions than those confronting Washington—has done far more to bring their long-term debt burden under control.

One of the biggest policy shifts in Europe has been the cutbacks to public pensions, which had been soaring with the growing number of retirees. Most of the reforms now link benefits to some automatic cost-control measure. In Germany, for example, benefits will go down as the ratio of taxpayers to pensioners declines. In Italy, the pension age will go up at a rate that is tied to life expectancy gains, while France indexed part of its pension system to price inflation. Altogether, these changes amount to huge spending cuts by 2040 compared to previous law—by roughly 30% in France, by 40% in Germany, and by nearly 50% in Italy.

On health care, the other big cost for most governments, Europe has also done far more to tackle the problem. Remarkably, Germany and Italy, whose populations are among the oldest in the world, are projected to have almost no growth in public health care costs, apart from costs related to unavoidable population aging. The US, in contrast, is projected to have the highest health care cost-growth in the G7—and a disproportionate share of that growth will be the preventable kind, like spiraling prices or patients using services they don’t actually need.

The US has so far been unwilling to make similarly tough decisions, even though these decisions should actually be easier for the US than for Europe. The US population is younger. The average older American is wealthier, retires later, and depends more on private savings and less on public pensions. The US also has more room to raise taxes, with tax revenue consisting a much lower share of GDP than in Europe. And economists expect economic growth to be stronger in the US than in nearly every other G7 country.

But the American public is in no mood for tough budget decisions. Public opinion polls consistently show that while Americans support a balanced budget, they oppose most of the specific measures—such as cuts to social security or Medicare, or tax increases—that could bring the budget into balance. In contrast, there is a broad understanding among the European public that future pension promises had to be scaled back.

The tragedy of the recent era of budgetary wrangling, with debt ceiling brinkmanship and high-flying rhetoric about the federal debt, is that congress and the president managed to accomplish so little but did so much harm. Debt-reduction measures closed deficits in the near term, putting the brakes on the economy, without making a serious dent in the long-term debt problem. And austerity through the across-the-board sequestration cuts was aimed almost exclusively at discretionary spending, which was set to decline anyway and hurt the small parts of the federal budget that promote economic growth like education, infrastructure, and research. Changes to entitlements and taxes—the only way the budget can be balanced in the long term—were all but left out.

A solution may not come any time soon, either. The FY15 budget proposals submitted by the president and House Republicans would both moderate the long-term debt trajectory. And both plans agree on the need for serious Medicare cost control. But neither touches social security, and Obama has even backtracked on a proposed social security reform in his previous budget. The Republican plan, meanwhile, would make far deeper cuts to discretionary spending, some four times what is being slashed under sequestration. Obama’s plan relies on big tax hikes, which House Republicans steadfastly oppose. But regardless of whether Washington elites can agree on a reform plan, the biggest challenge of all will be to get the American public on board. Americans will first need to embrace a more European steeliness to stomach any serious reforms.