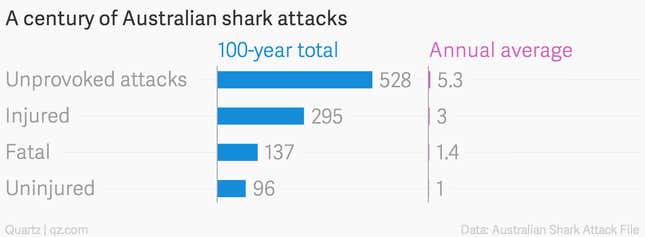

Seven in three years—that’s how many people have been mauled to death by sharks in Western Australia. That’s spooked the state’s tourism business enough that in early 2014, the government launched a $1.3-million shark cull using baited traps called drumlines to catch big sharks that could potentially hurt humans.

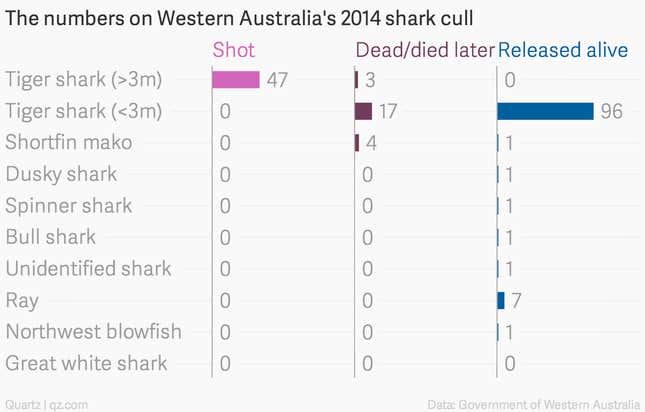

As Quartz explained at the time, not only is there no clear evidence that drumlines alone prevent shark attacks, there’s also plenty of proof that they kill indiscriminately, including endangered species. In some cases, they might make beaches even more dangerous.

Conservationists can stop fretting, though. The WA government just announced that it’s scrapping the plan, after the state’s Environmental Protection Agency said that the drumlines posed too big a potential threat to migratory shark populations given the available science, recommending the program’s termination.

The program, which authorized the shooting of any sharks bigger than three meters (10 feet), say 50 such sharks have been killed, including five in excess of four meters; the largest was 4.5 meters. Of the 172 sharks snagged none of them were Great Whites, the species thought to be responsible for several recent maulings.

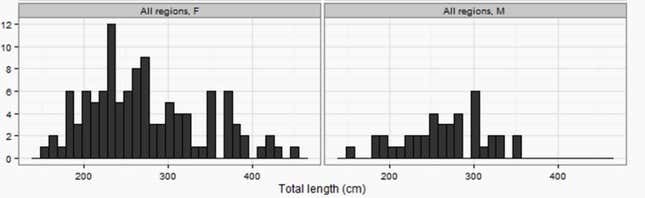

That’s probably a good thing; Australia’s Great White population is in a shaky state. However, more than seven in 10 of the Tiger sharks (pdf, p.22) caught were female, and about the same ratio was destroyed. Though Tiger sharks aren’t considered a vulnerable species in Australian waters, this is potentially worrying given the impact to their birth rates.

And despite all this shark-slaughter, a man may still have been killed: In March, the body of a diver was found south of Perth with what appeared to be shark bites. (Days ago, a shark killed a man in New South Wales, which also has a shark-control program.)

Though it says it won’t appeal, the government isn’t thrilled. Colin Barnett, the state premier, suggests the problem is a “rogue shark, one that stays in one area for repeated periods,” that needs to be killed. That’s despite the fact that, from January to April, none of the 90 sharks that the program caught and tagged for research purposes reappeared.

Though the demise of WA’s shark cull might be a coup for conservationists, it doesn’t help with the very real problem of frequent, lethal shark attacks. Is there an effective—and less destructive—policy out there?

Marine biologist and shark expert David Shiffman argues (paywall) drumlines are actually the best way to limit the risk of shark attacks on humans—provided that a team of monitors hauls up the sharks and moves them to where they won’t threaten swimmers (which the WA team wasn’t doing). The crew also must haul up the drum lines frequently enough to make sure no sharks or other animals drown on their hooks.

That might sound too good to be true. But scientists using the method in Recife, Brazil—a major shark-attack hotspot—report a 97% fall in bites.

But perhaps above all a little perspective is due. As Shiffman points out, vending machines, toasters and cows kill more people each year than sharks do.