It’s nearly official. The Federal Reserve confirmed yesterday that if all goes according to plan, it will finally stop its policy of creating new money from thin air and using it to buy financial assets.

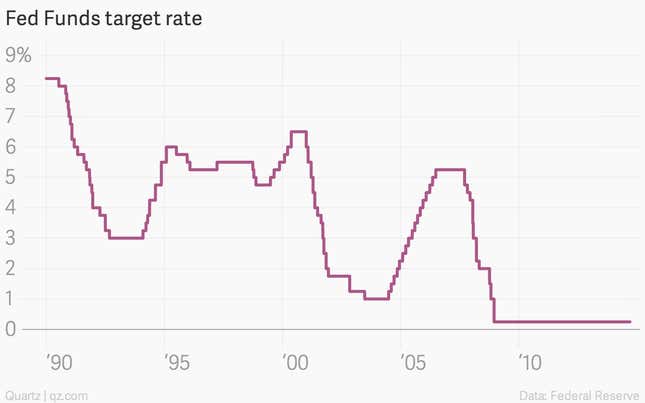

This practice, better known as “quantitative easing,” is what central banks do when interest rates are stuck near zero and can’t be lowered any more. (Like lowering interest rates, QE represents an “easing” of financial assets, by boosting the quantity of money, or at least of the money-like substance that the Fed actually creates: bank reserves.)

During the crisis, the interest rate the Fed traditionally uses to make financial conditions tighter or looser hit zero pretty quick.

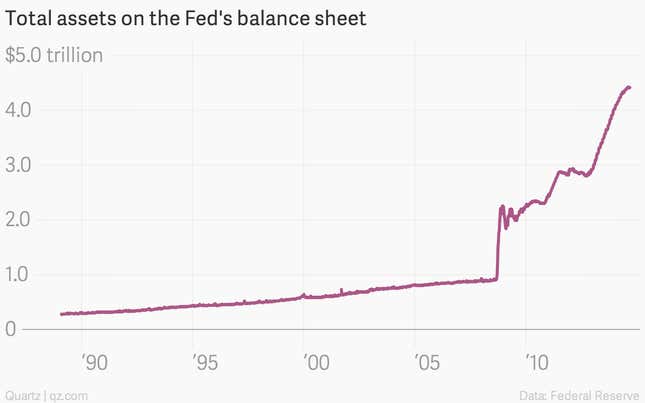

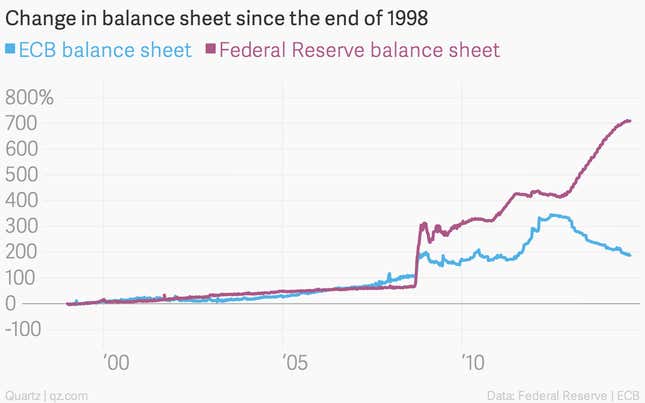

So the Fed then switched to quantitative easing to try to support the economy. It was QE—it came in a number of stages—that ballooned the Fed’s balance sheet in recent years. At last glance, the Fed’s assets totaled about $4.42 trillion.

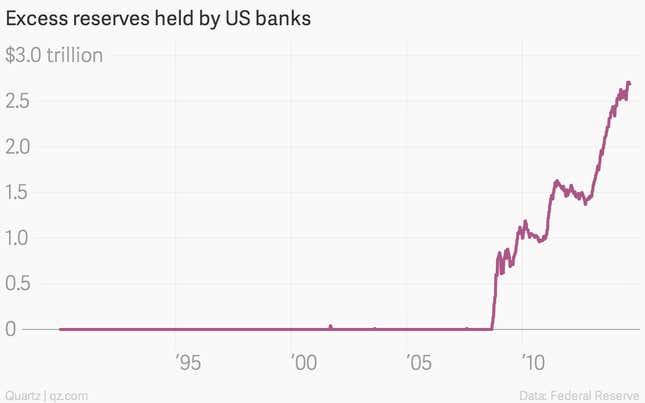

The chart above looks like a pretty radical policy. Isn’t that a potentially dangerous amount of money creation? Some have argued that by creating a ton bank reserves, the Fed has essentially set stage for an inflationary conflagration. The Fed says no, that things might have worked that way in the past, but now that the central bank has the ability to pay interest on excess reserves, there’s no reason to worry (pdf).

Now, if all that money was just sitting parked at the Fed, it raises a question: Did QE actually do anything?

Well, to be honest, nobody really knows for sure. Economics is a social science, not a hard science. It’s not like we’re running these experiments under ideal conditions and clinical isolation.

Critics might point to statistics such as the “velocity of money,” which show that the rate at which money passes through the economy has continually declined in recent years. They argue that this shows the Fed’s money-creation policies have been ineffectual.

But there clearly have been impacts. QE is widely credited—or blamed—for boosting the prices of assets such as stocks. While the US economy has had a tough run, the US stock market has had a fabulous one over the last few years, helping repair the balance sheets of American households. (It’s true that the stock market surge has disproportionately helped the richest Americans. But it has also likely helped overall consumer sentiment, at least a bit.)

And the QE program has helped keep interest rates low, which also helps to support the economy by allowing some refinancing to take place and by lowering borrowing costs for things like home and auto loans.

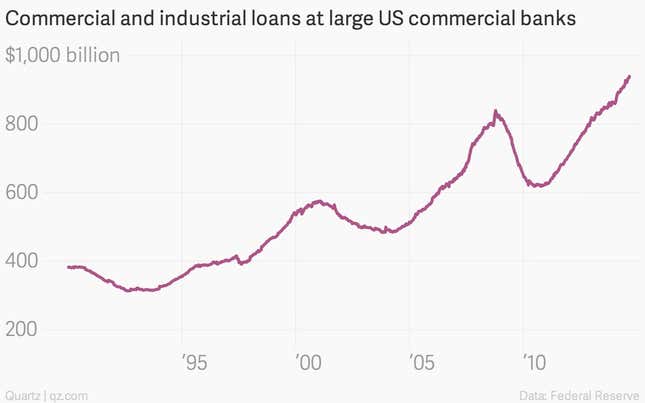

And while it’s impossible to prove causation, a sharp curtailment of business lending activity began to turn not long after the Federal Reserve began pumping vast quantities of cash into the system with QE.

Another thing to consider is that while it’s unclear how much the Fed’s QE policy helped, it’s equally unclear how much worse things might have been in the US without it. But there are some hints. In the US, the Fed’s QE was part of a fast, aggressive approach to counteracting the pernicious aftershocks of a major crisis.

In Europe, the central bank didn’t embark as aggressively on the same kind of balance-sheet-based easing program:

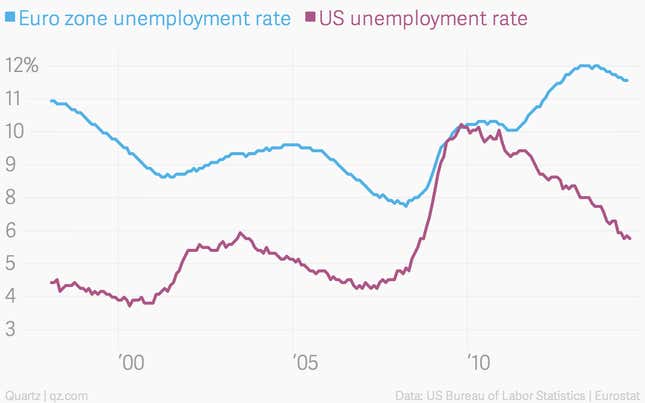

And the outcomes in the US have been much better, with the unemployment rate falling sharply, in comparison to the euro zone.

Given that the Fed’s aggressive balance-sheet expansion was a key distinction in the policy responses of the US and euro zone, it would seem to be foolish to dismiss its impact.