Amazon.com went public 15 years ago but it has long been famous for its secretiveness. So when UK parliamentarians got enraged on Nov. 12 by the evasive answers they got from Andrew Cecil, Amazon’s director of public policy, they were merely joining the ranks of a generation of frustrated journalists and analysts.

Cecil was testifying at the request of lawmakers who wanted to know how Amazon paid less than £1 million in income tax last year on UK sales topping $5 billion. He repeatedly refused to give answers, or didn’t know the answers, to some surprisingly basic questions, like the company’s sales in Britain, or who owns the holding company that owns Amazon EU in Luxembourg. Committee members called him “evasive” and “ridiculous”, and you almost felt sorry for Cecil with his hangdog expression. (Almost.) Exasperated, Margaret Hodge, the committee chairwoman, fumed:

You’ve come with nothing! We will have to order a serious person to appear before us and answer our questions.

Good luck.

Cecil was in all likelihood, doing what any good Amazon executive would do: duck and weave. Company executives, from the top down, have long refused to reveal fundamental data about Amazon’s business including sales by markets (Cecil says they’re not broken down), number of employees by country, and how much Amazon spends on investments, let alone how many Kindles it sells.

Amazon isn’t the only culprit here. Many technology companies fail to disclose the kind of information routinely divulged in other industries. Apple, for example, is so evasive that there’s a cottage industry of bloggers devoted to extracting details of Apple’s sales figures from the company’s opaque numbers by cross-referencing disparate bits of data.

At Amazon, though, evasion is really more of an art. Here’s are some classic answers from Amazon executives on fairly straightforward subjects:

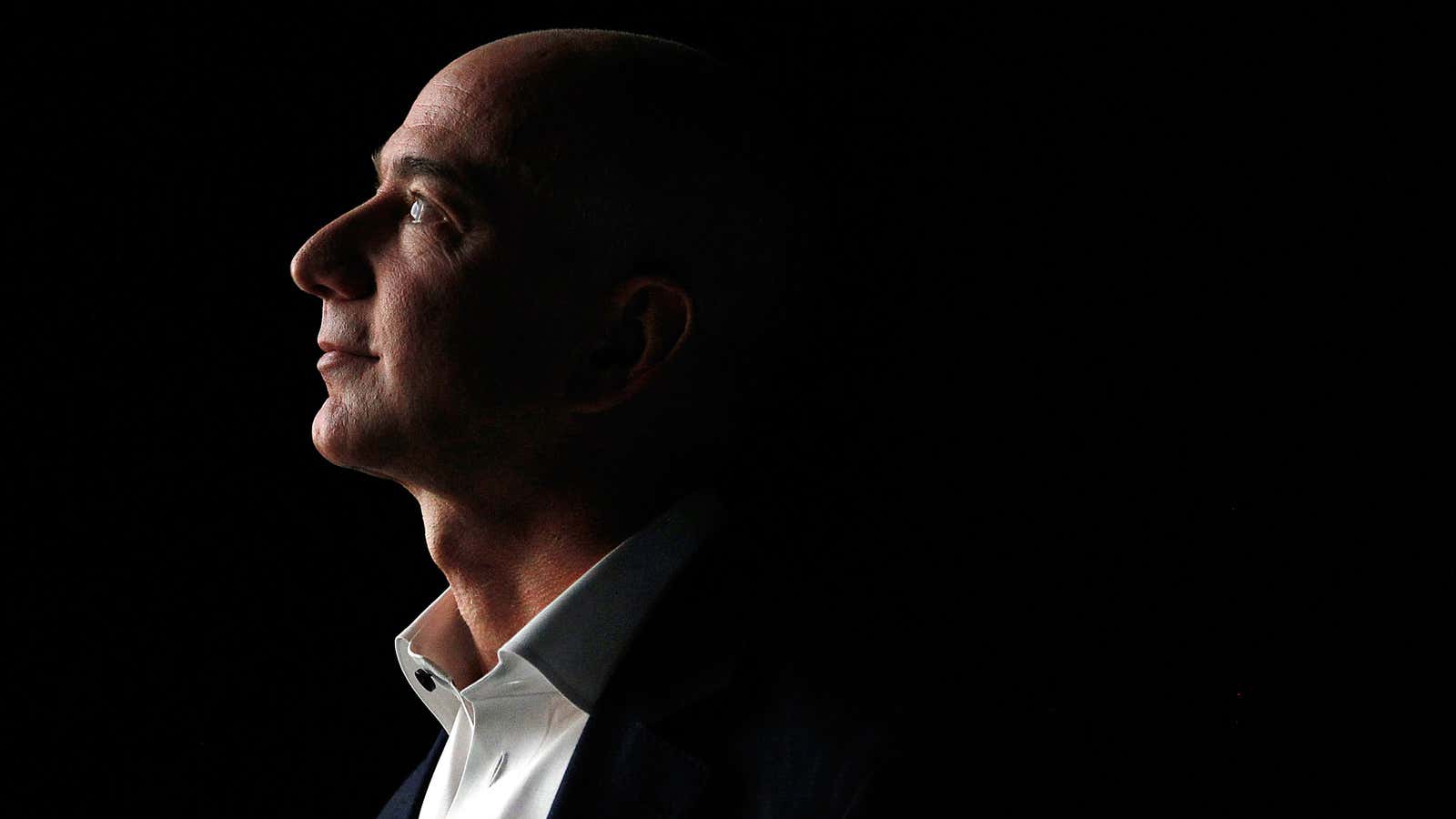

CEO Jeff Bezos during Amazon’s third-quarter 2012 report, where unit sales of various products were not revealed, while the percentage of pixels on the Kindle Fire HD, compared to the iPad mini, were. (The Kindle has more.) Bezos said:

The next two bestselling products worldwide are our Kindle Paperwhite and our $69 Kindle. We’re selling more of each of these devices than the #4 bestselling product, book three of the Fifty Shades of Grey series.

Amazon CFO Tom Szkutak, speaking to analysts about these same third-quarter results, said he couldn’t offer specifics on sales of digital content for Kindle devices, but could reveal:

We like what we see there. That’s why we continue to invest in that business.

Szkutak at Amazon’s first-quarter 2012 results meeting with analysts, after dodging a number of questions and refusing to answer others, is asked about the Amazon Appstore and how its content is selling on Android devices, and specifically, the Kindle Fire. He says:

It’s early, so there’s not a lot I can do. We’re excited about it. We think it’s a very interesting opportunity and happy to do that on behalf of our customers. But stay tuned, and it’s early.

Or take its response to Der Spiegel last year, when asked how many temporary staff repeatedly underwent unpaid training, thereby enabling Amazon to take advantage of German job creation subsidies:

“We have turned several hundred temporary contracts into permanent contracts each year in recent years at our Bad Hersfeld site,” the company says. Creating permanent jobs is the general long-term goal, but only “when our business growth allows it.”

Perhaps its Bezos who really sums up the company’s communication strategy best. When speaking of innovation and overarching plans last year, he said: “…we are willing to be misunderstood for long periods of time.” Tech columnist Farhad Manjoo took a different view: “Amazon is not merely ‘willing’ to be misunderstood, it often tries to actively sow widespread misunderstanding.” The MPs are not alone in their confusion.