Chinese censors are trying to erase Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement

HONG KONG—China’s government is scrambling to keep its citizens unaware of pro-democracy protests that have paralyzed Hong Kong, the semi-autonomous territory where demonstrators are demanding free elections and more independence from Beijing.

HONG KONG—China’s government is scrambling to keep its citizens unaware of pro-democracy protests that have paralyzed Hong Kong, the semi-autonomous territory where demonstrators are demanding free elections and more independence from Beijing.

Most Chinese websites have been ordered to wipe any mention of “Hong Kong students violently assaulting the government and about ‘Occupy Central,'” one of the groups organizing the protests. If state-run news sites are mentioning the demonstrations at all, they are running official statements and op-eds condemning them as illegal protests that “spun out of control.”

On social media, censors are also moving quickly. One mainland student in Hong Kong told Quartz that her photos and videos from the protests began to be blocked on the messaging app Weixin (known in English as WeChat) last night, and Facebook’s photo sharing app Instagram also appears to be blocked in major Chinese cities.

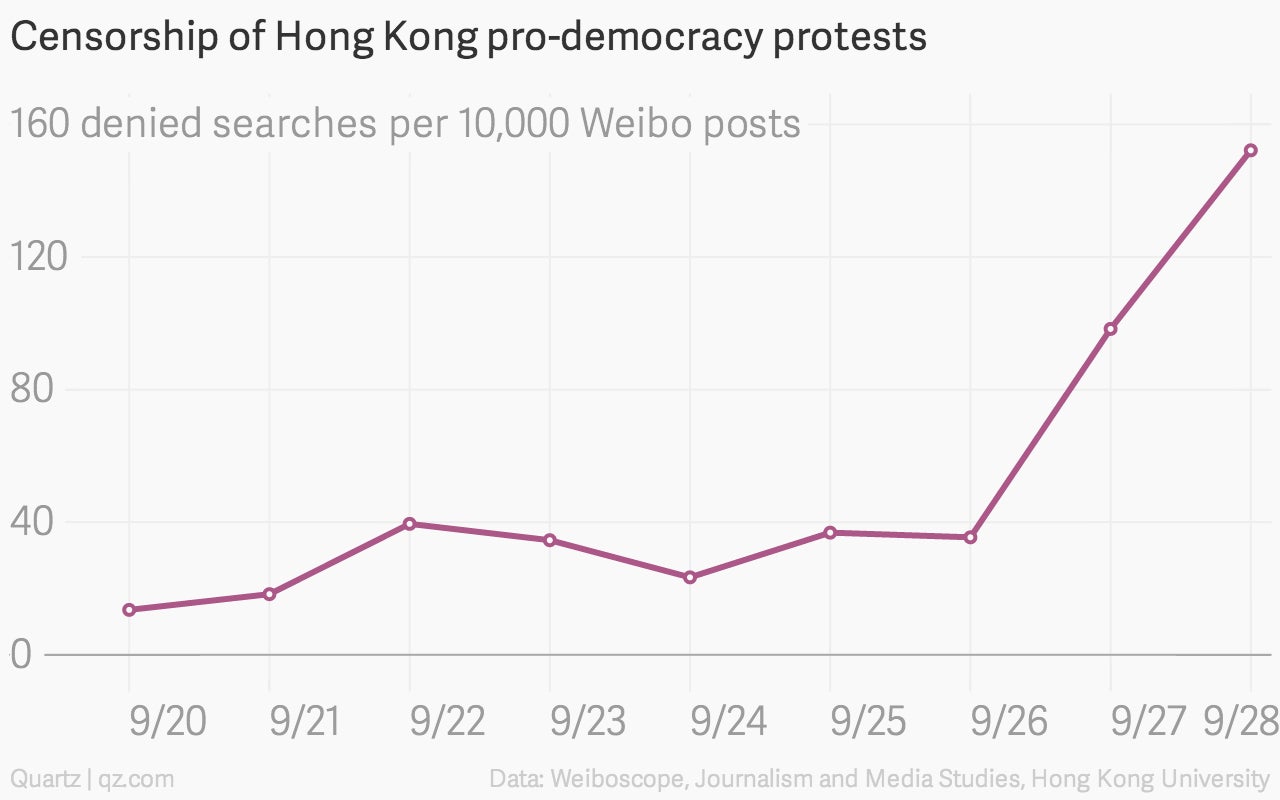

The number of times search queries on China’s Weibo microblog has prompted a “permission denied” notice has more than quadrupled to 152 per 10,000 published posts yesterday—up from only 35 on Friday, when students demonstrations kicked off a wider protest movement. Terms like ”Hong Kong,” and “police” were censored the most on Saturday and Sunday.

Despite the attempt at an information blackout, it’s obvious that mainland internet users are interested in what is happening in Hong Kong. Before censors tightened their reins on Weibo, “Hong Kong” was a trending topic. On FreeWeibo, a website that publishes deleted Weibo posts, “Hong Kong” and “Occupy Central” were the two top searches today.

“They are our brothers and sisters. They’re Chinese,” said a 28-year-old pharmaceutical researcher in Chengdu who would only give his surname, Li. “How the government treats them is how they will treat us.”

Li says he has been following the protests closely on Weibo and Weixin, even though those platforms are also quickly being censored. “It’s difficult, but it’s all I have,” he told Quartz.

Bloggers are findings ways to get around the censors by searching for the English transliteration of blocked Chinese phrases—substituting “xianggang” for Hong Kong or “zhanzhong” for “Occupy Central,” for example. Entering a space in between the two Chinese characters for Hong Kong is another way around the restrictions, Li said.

Censors are adapting swiftly. Searching for the phrase ”zhanzhong” already prompts a notice on Weibo that results cannot be displayed. Even posts critical of the protesters are being removed, including a comment that read, “So violent like this, and you tell me you want democracy. I don’t want this kind of democracy!” was deleted.

Ultimately, one result of China’s far-reaching censorship of the protests is that thousands of mainland tourists planning to visit Hong Kong on Oct. 1, China’s National Day, for a shopping excusion may get an unexpected lesson in democracy instead.

While communication is still relatively unencumbered in Hong Kong, demonstrators are preparing for the worst. After rumors that authorities were planning on shutting off mobile networks near protest sites, at least 100,000 people in the city downloaded a free “off-grid” messaging app called Firechat, which allows users to communicate over Bluetooth, even without cellular coverage or wifi.