Hong Kong’s democracy movement has moved way beyond just students

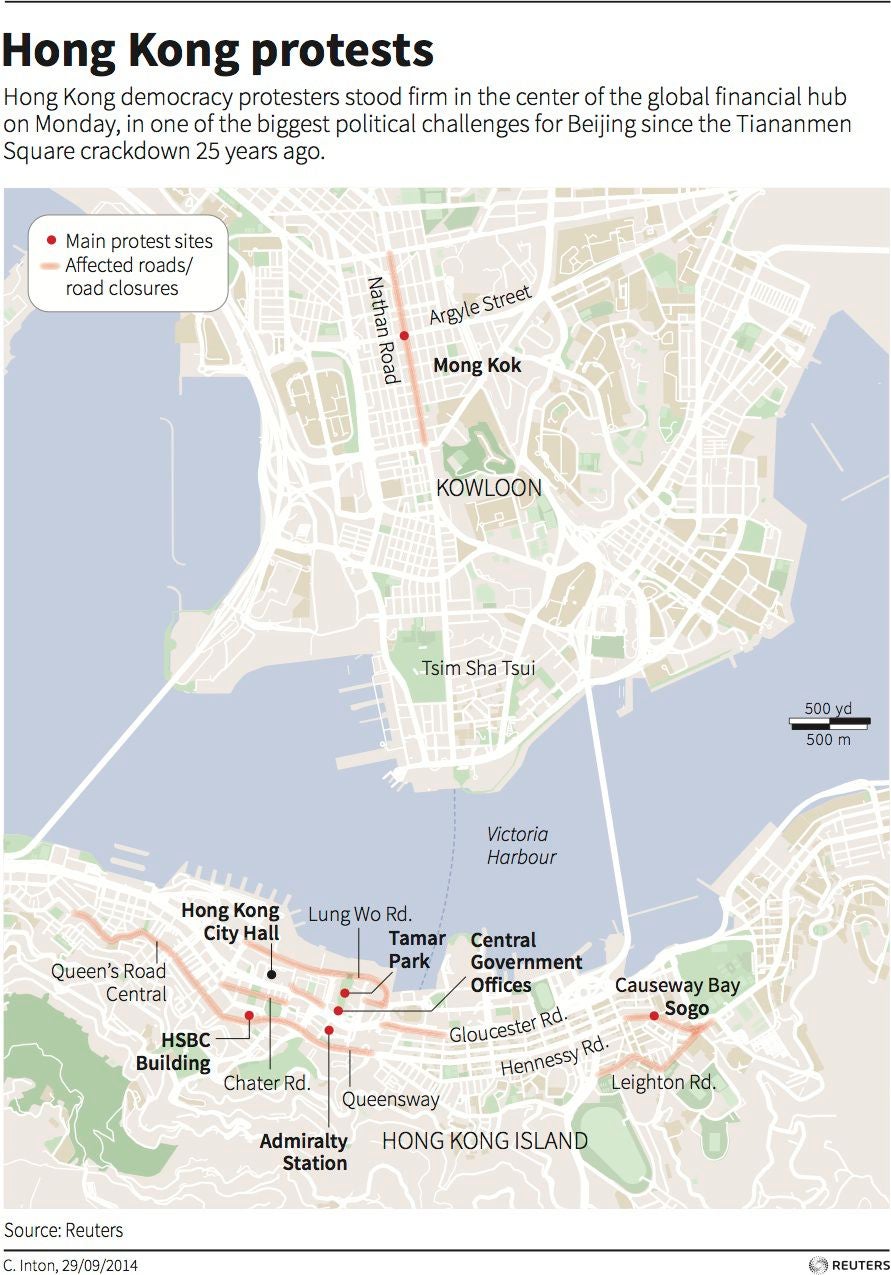

HONG KONG—While tens of thousands of students continue to paralyze Hong Kong’s financial and commercial districts for a third day to demand free elections, across Victoria harbor in Kowloon the pro-democracy movement is starting to look a little different. In Mong Kok, a dense working class neighborhood, demonstrators are older, quieter, and in some ways, a little more cynical.

HONG KONG—While tens of thousands of students continue to paralyze Hong Kong’s financial and commercial districts for a third day to demand free elections, across Victoria harbor in Kowloon the pro-democracy movement is starting to look a little different. In Mong Kok, a dense working class neighborhood, demonstrators are older, quieter, and in some ways, a little more cynical.

“The politics here are so bad. That’s why we have to fight for democracy,” 78-year old Li Kon-wah tells Quartz. Li says Hong Kong’s top official, the chief executive CY Leung answers only to Beijing, a government that he remembers most for having ordered a violent crackdown on nonviolent democracy protesters in 1989. “I was so angry. I cried,” he says, after carefully taping a sign onto a nearby bus that reads, “Blood bath Tiananmen Massacre.”

What started as a pro-democracy movement mainly among the city youth—sparked by student activists as well as another pro-democracy group, Occupy Hong Kong—is starting to capture a broad cross-section of the city’s population of seven million. The majority of these residents initially opposed Occupy’s strategy—to disrupt the city’s economy and force the government to withdraw electoral reforms that give Hong Kongers direct elections in 2017 but allows Beijing the ability to vet candidates for the city’s top office.

Now, news reports and footage of police clashing with students, as well as tear gassing or pepper spraying them, have brought more people into the streets. In Mong Kok, thousands of demonstrators, including students, retired local residents, and workers have overtaken Nathan Road, a main thoroughfare. They are decorating streets with chalk drawings of umbrellas—the latest symbol for the demonstrations—and plastering signs on a row of buses that had to be abandoned when drivers couldn’t move in crowds that descended on the street late Sunday.

Elderly demonstrators like Li mill around the area listening to speeches, handing out yellow ribbons and leaflets. Another retiree, Chan Kin-hoi, 76, wears a hat with a sign that reads, “Oppose the communist party, save Hong Kong.” Chan says: “I’m here because I support universal suffrage.” Local workers, like delivery drivers have volunteered to bring goods to demonstrators.

Young and middle-aged professionals are also joining the protests during work breaks or after work. Grace Fu, 22, who works at an office nearby, is under no illusion that the protesters’ demands will be met. Chief executive Leung said again today the government will not change its stance on how Hong Kong elections will be run, despite the spread of ”illegal” protests.

But, says Fu, “Even if this movement doesn’t change anything, it’s good that people can now know what’s going on in Hong Kong. That would still be worth it.”

Other segments of society are joining, too. Teachers in at least 31 secondary schools are boycotting classes, and Hong Kong’s Professional Teachers Union (PTU)—80% of the city’s primary and secondary school teachers are members—has pledged its support to the movement. Instead of teaching classes, teachers are holding “civic lessons” for students to learn about Hong Kong politics and activism, according to Fong King-lok, head of computer development at PTU.

And though many of Hong Kong’s construction workers, drivers, small shop owners and others are apolitical, at least one organized group of workers is participating—a development that labor observes say could eventually be similar to the support workers gave gave pro-democracy student activists in China in 1989. One of the city’s most influential trade groups, the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions, has called on workers to strike and demonstrate at protest sites. Support from other unorganized workers has trickled in as well: 200 delivery workers at a Coca Cola plant have also gone on strike.

These workers may have even more reason to push for genuine direct elections than students, many of whom feel their economic and career prospects have been compromised by the current government. Collective bargaining for workers is weak—workers often have to accept poor terms and can be let go for striking.

“Organized workers as a group feel that they have as much at stake as anyone,” says Rick Glofcheski who teaches labor and employment law at Hong Kong University. “The thin blanket of protections workers are offered has to do with lack of accountability of the government in Hong Kong. The workers have a strong conviction about that.”

Activists have said they plan to keep protesting until Leung steps down; Leung himself says he expects the protests to last “quite a long period.”

By early evening today, more people had started streaming in to Nathan Road to support the demonstrators. A 63-year old woman who would only give her surname, Li, sat along a traffic barrier, chatting with her sister and other neighbors. Asked why she’s come, Li says: “It’s our responsibility as Hong Kongers. If we don’t come out today, when will we?”