What it will take to convince Americans to embrace more free trade

Today, the US trade deficit shrunk unexpectedly as a new record in oil sales abroad boosted American exports. Though exports have helped boost the economic recovery since the 2008 financial crisis, American elites worry that growing populism, driven by fears of lost wages exploited by opportunistic politicians, is a major barrier for the US effort to ink major international trade deals.

Today, the US trade deficit shrunk unexpectedly as a new record in oil sales abroad boosted American exports. Though exports have helped boost the economic recovery since the 2008 financial crisis, American elites worry that growing populism, driven by fears of lost wages exploited by opportunistic politicians, is a major barrier for the US effort to ink major international trade deals.

“Most Americans believe trade is going to hurt them,” John Veihmeyer, the chairman of the auditors KPMG International, said. “Joe Public on the street has heard the soundbite,” Irene Dorner, the CEO of HSBC USA, said. “People are running for cover,” Jon Huntsman, the former US Ambassador to China, added. “If we were to take any kind of vote on Capital Hill, I’m not sure it’ll pass. I’m not sure we’d be able to do what we’d done in the past, where there was kind of a bipartisan consensus. I’m not sure that exists.”

These leaders in business and politics had gathered at an event organized by HSBC, a bank that finances 10% of global trade. The bank’s executives have been barnstorming the country, trying to whip up support for new trade deals with a coalition of Asian countries and the European Union.

Trade is win-win, they argue, and they have the charts to prove it, thanks to analysis by the Dartmouth economist Matt Slaughter—US exports have doubled in absolute terms since 2003, trade companies pay 15 to 30% higher wages, the elimination of barriers to trade has boosted US national income by 10 percentage points annually. Those gathered at the event in Washington, DC seemed baffled at the idea that anyone might regret free trade deals—and they blamed misinformation.

“People have internalized the benefits of free trade so much,” Honest Tea CEO Seth Goldman said, adding that Americans may not know it. After all, he couldn’t make his beverages without importing tea grown abroad, and there’s no iPhone without a global supply chain.

But all of this does some injustice to the American people’s intelligence. According to recent polls, 68% agree that “trade” is a good thing for the economy, but many more are skeptical that it creates jobs (just 20% believe it does) or raises wages (only 17%).

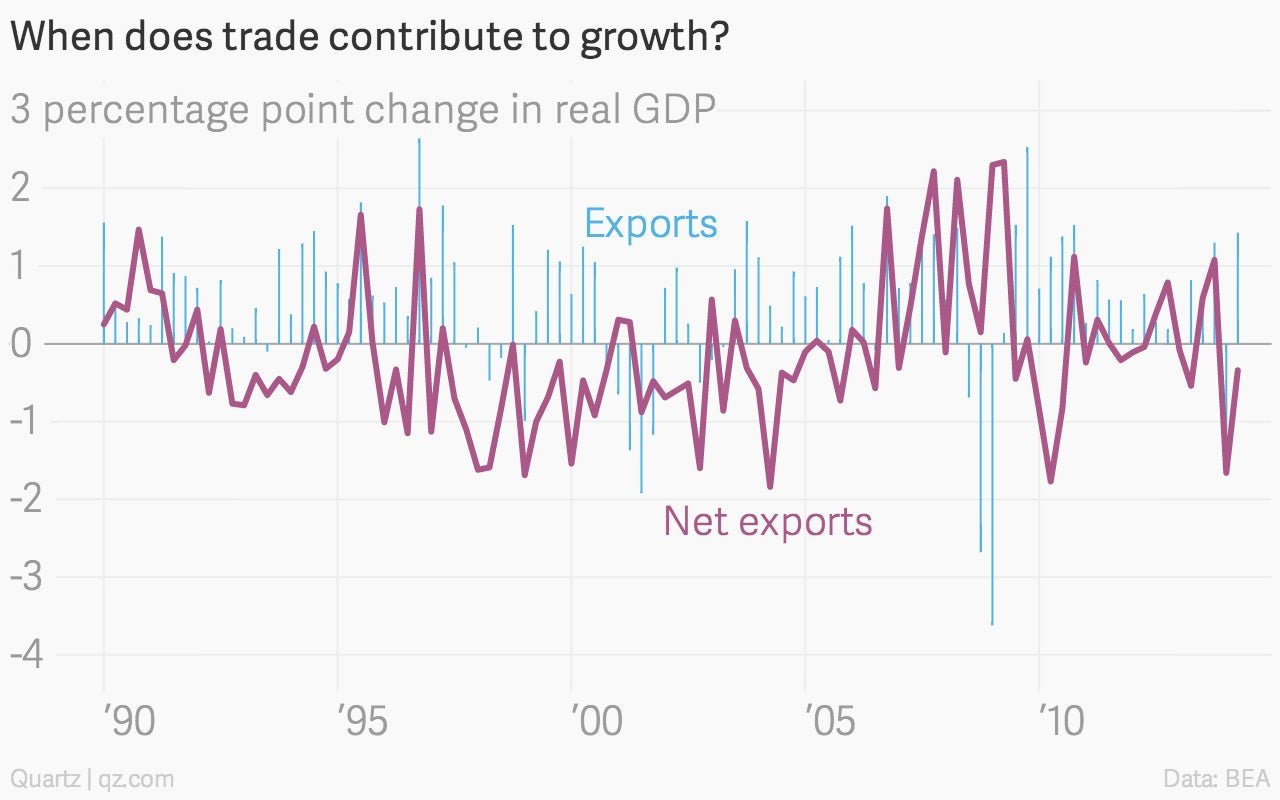

For all the talk of exports growth, a fuller story compares looks at both exports and net exports, as the chart below does: For about a decade from 1996 to 2006—the period coinciding with the introduction of the North American Free Trade Agreement and trade liberalization with China—trade was a net drag on the the US economy as Americans purchased more goods and services abroad then they sold.

It’s no coincidence, some economists argue, that wages in sectors most affected by import have fallen—and indeed, they say that trade explains the bulk of wage reductions in the last 25 years. Trade has diffuse benefits for the entire economy, but very concentrated negative effects on a few key constituencies. At the event, Dorner observed that “if you’re here, you probably agree with us.” There was probably a similar consensus the other cities HSBC visited on its trade push: Los Angeles, where the film industry plans around Chinese distribution; San Francisco, home to the digital economy; Houston, a city built on the petroleum trade; and Chicago, the fourth-largest exporter in the country.

Not on HSBC’s itinerary: The rust belt cities of Detroit, Pittsburgh, and Cleveland, or South Carolina’s textile counties. And while the benefits of trade were touted at HSBC’s events, there was little discussion on how to help the people who absorb the negative impact.

Indeed, the system designed to address that problem—the US Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) policies set up to help displaced workers gain new skills and stay employed—is widely regarded as broken and ineffective. In this 2007 report, Slaughter suggests that the many parts of TAA be incorporated into the unemployment insurance system, and bolstered with relocation and retraining assistance. This is an agenda begging for an update.

And while the economic argument is perhaps the largest obstacle to new free trade deals, almost nothing was said about concerns that Americans may legitimately have about opaque trade negotiations, provisions that might give multinational corporations unfair power over developing economies, or weak labor and environmental standards that leave Americans complicit in sweatshops and child labor. Nor does it touch on the complicated politics of currency manipulation, which will only become more important if the US dollar continues to strengthen.

None of that makes new trade deals a bad idea: It just means a bad trade deal is a bad idea. As Karan Bahtia, the top international lawyer at General Electric, observed, global growth trends mean that US economic sustainability “is going to depend on being more deeply engaged in the global markets.” After all, 95% of the world’s consumers live outside the United States.

But selling the American people—and American politicians—on the deal will require more than telling trade’s winners what they’ve already won. It’ll mean telling the losers what’s going to be different this time.