It’s time to party like it’s 2008. That year, in the halcyon days just before the collapse of Lehman Brothers hastened the deepest financial crisis in decades, a mere 6% of working-age Brits—1.8 million of them—didn’t have a job.

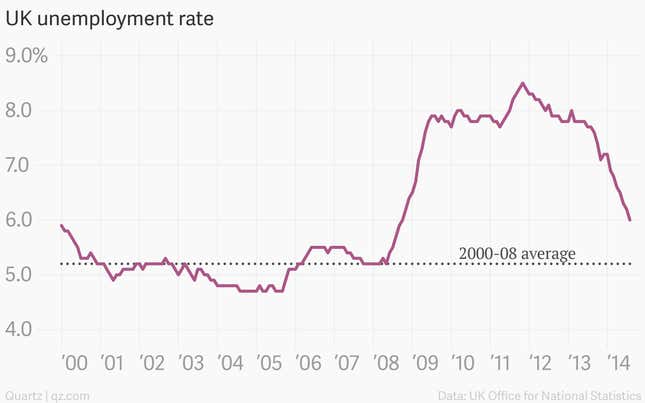

When other banks blew up and economies cratered, the long-running crisis threw nearly 1 million more Brits out of work. By November 2011, the unemployment rate was 8.5%. But now things are back where they started—the data today puts the UK’s unemployment rate at 6% (for the three months to August), the same as in late 2008:

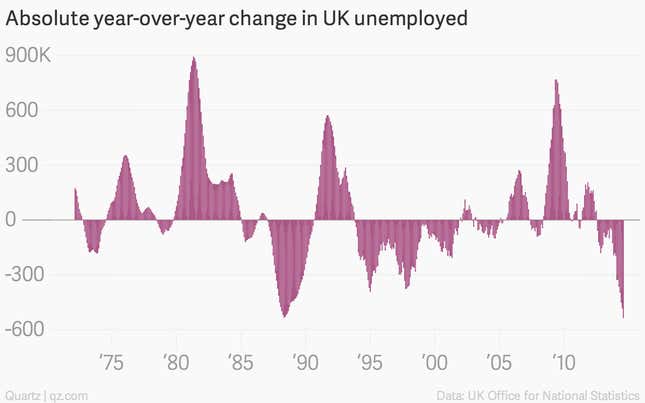

There is still a ways to go before the unemployment rate falls to its pre-crisis average, but the rate of recent improvements suggests that this won’t take too long. In fact, in absolute numbers, the year-over-year drop of 538,000 in Britain’s unemployment rolls was the largest ever recorded:

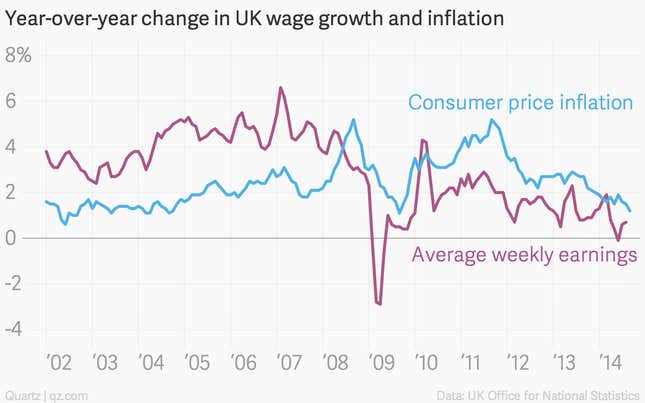

This is a stat that prime minister David Cameron is sure to cite frequently when the campaigning for next year’s general election gathers pace. But Ed Miliband, whose Labour Party is narrowly ahead of Cameron’s Conservatives in the polls, will stress a less encouraging feature of Britain’s job market—weak wage growth:

Over the past six years, the average worker’s earnings have grown faster than inflation on only three occasions, according to the monthly data. Earlier this week, midwives, ambulance drivers, and other National Health Service workers staged a strike over pay for the first time in 30 years (that’s one of them in the photo above).

When British politicians go toe to toe in parliament and on the campaign trail, expect one side to trumpet its success in reviving the job market and stoking world-beating economic growth, while the other decries the false economy of zero-hour contracts and warns of a cost-of-living crisis. It’s no wonder that voters seem torn—in many ways, both sides are right.