Poor voters aren’t bad for Hong Kong—prosperity and democracy often go hand in hand

HONG KONG—Hong Kong’s chief executive CY Leung’s recent claim that Hong Kong’s citizens were too poor to allow direct elections was greeted with outcry here and astonishment overseas.

HONG KONG—Hong Kong’s chief executive CY Leung’s recent claim that Hong Kong’s citizens were too poor to allow direct elections was greeted with outcry here and astonishment overseas.

“If it’s entirely a numbers game and numeric representation, then obviously you’d be talking to the half of the people in Hong Kong who earn less than US$1,800 a month. You would end up with that kind of politics and policies,” he said. Numeric representation is at the heart of what Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement protesters want—the right to choose their own candidates to replace Leung in the next elections, a more democratic method than having candidates vetted by a Beijing-leaning, business-friendly committee.

Despite Lueng’s suggestion that democracy could be dangerous to Hong Kong’s prosperity, much of the available evidence points in exactly the opposite direction—the world’s wealthiest countries are also its most democratic.

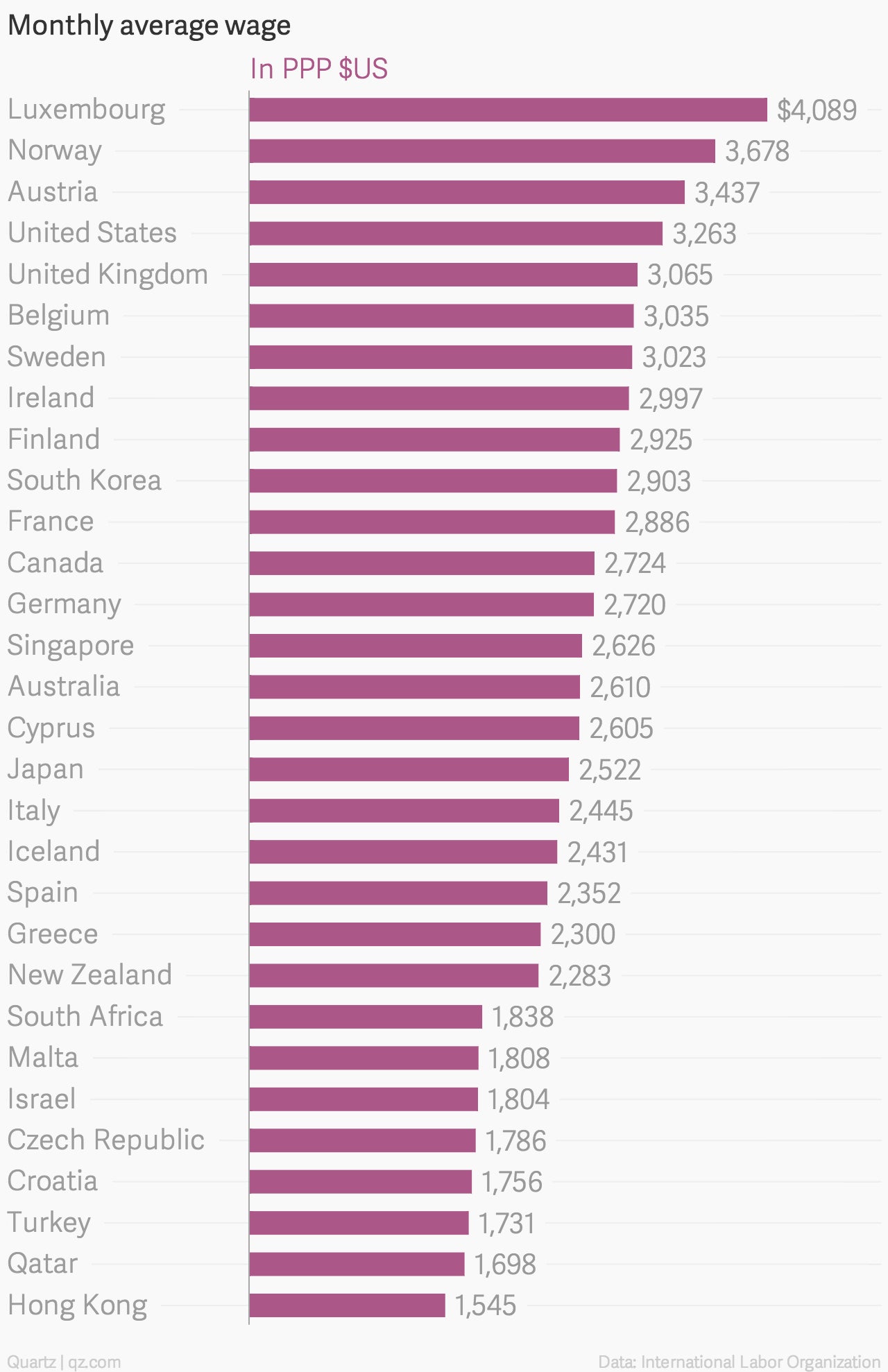

Leung was referring to the city’s latest annual statistics, which show the median monthly wage in Hong Kong is $HK 14,000 ($1,800), if you exclude government workers, interns, and the hundreds of thousands of immigrant domestic helpers who make about $500 a month (the helpers can’t vote here anyway). Many countries more regularly report mean, or average monthly income instead so we’ve compared these figures, although they flatten out inequality. On this basis, Hong Kong ranks 30th in the world, if figures are adjusted for purchasing power parity, or how far incomes go in a given location.

All of the world’s 28 wealthiest countries, using this measure, are democracies.

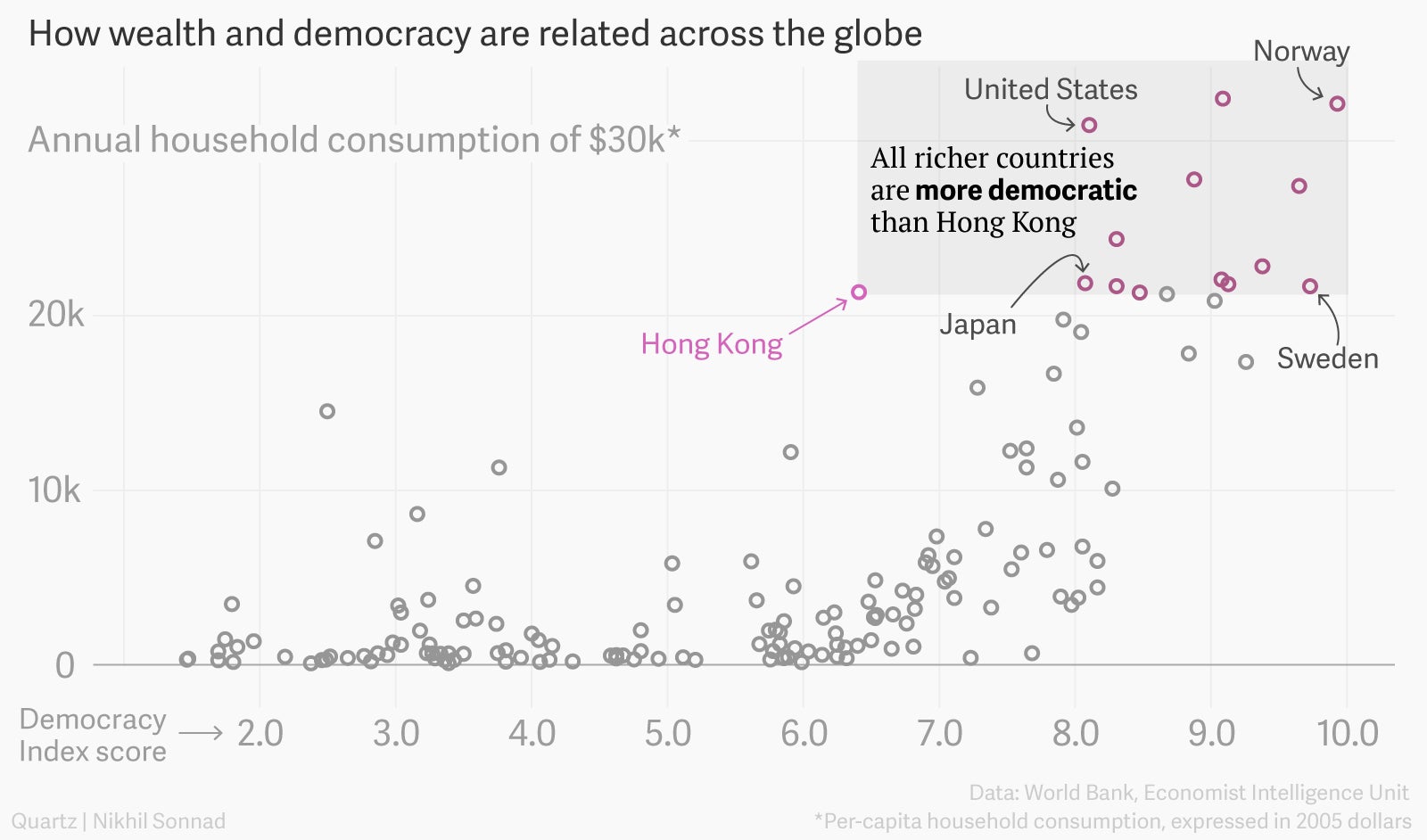

Looking at per capita household consumption, another measure that some economists believe is a better indicator of citizens’ quality of life than income, every country that is richer than Hong Kong is also more democratic, based on the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index. The index, issued in 2014 based on data from the year before, defines Hong Kong as a “flawed democracy,” lagging behind Serbia, Mongolia and Columbia.

Whether democracy promotes economic growth or vice versa (or if it is simply a matter of correlation rather than causation) is a debate that economists and social scientists have been having for decades. Economist Robert Barros’ study of three decades of global economic growth concluded that democracy enhances growth when political freedom is low, but depresses it after moderate freedom has been attained. A recently-published study from the Center for Economic Policy Research concludes that a country that switches from non-democracy to democracy increases its GDP by 20% in the next 30 years.

What Leung appears to be arguing—that less-wealthy people will vote for anti-establishment politicians, or at least those that are bad for business—has been also refuted by voters in long-established western democracies. In fact, the working class often leans towards conservative, business-friendly parties, particularly when the economy is going poorly, much to the puzzlement of social scientists.

Leung, who made his fortune in real estate, may not have followed the academic growth vs. democracy debates closely, or studied US voting patterns. But he is not alone in his line of reasoning: China’s phenomenal growth in recent years, particularly when contrasted with India’s relative stagnation, has led numerous observers to conclude that, as the economist and judge Richard Posner writes, “dictatorship will often be optimal for very poor countries.” Some, including author Martin Jacques (paywall), see China’s authoritarian government, rather than democracy, as a role model for the future:

Rather than dismiss the Chinese governing system as fragile and tenuous, we need to understand what has been, by the standard of the past three decades, an extraordinarily successful institution, one that the world will increasingly come to recognize it must learn from….There are strong historical reasons for believing that western democracies may face a difficult and uncertain future.

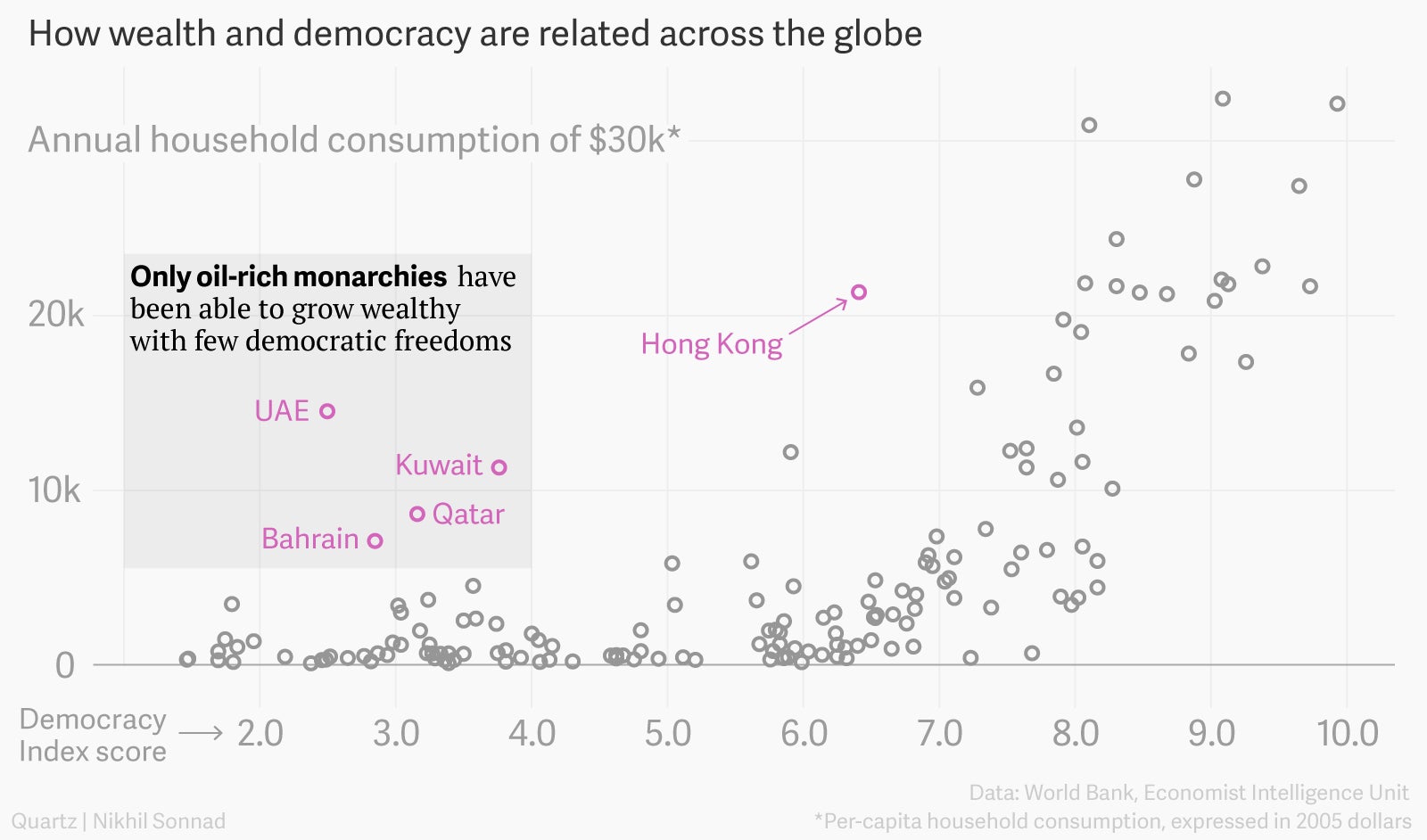

Western democracies are undoubtedly facing a difficult future. But at least to date, the only countries that have been able to achieve moderate levels of wealth while restricting democracy are the Gulf monarchies, propped up by massive fossil fuel reserves.

The momentum in the Asia is clear, the Economist argued last year: “Asia’s most successful economies are a mix of flawed democracies and hybrid regimes. Most of these are moving towards, rather than away from, democratisation.”

Hong Kong had been trending that way too—the city’s ranking on the EIU’s democracy index improved from 78th in 2007 to 65th in the latest poll. That number is likely to slip somewhat in the 2014 ranks, due to Beijing’s insistence on selecting candidates for the city’s elections. The longer-term impact on Hong Kong’s prosperity is less certain—though it will be closely watched by Leung, his bosses in Beijing, and Hong Kong’s 7 million citizens.