HONG KONG—Across Victoria Harbor in Mong Kok, Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement is quite literally divided. “This is the left-wing street and that’s the right-wing street,” said a student protester, gesturing to opposite sides of once-congested Nathan Road, lined with tents and tarps since pro-democracy protests began last month.

Student groups and left-leaning NGOs have collected mostly on the western side of the street, while more radical groups that call for more extreme protest actions stay on the east side. ”They say that Mong Kok does not belong to the students,” the student protester explains. She asked not to be named because of criticism that she says she already receives from the groups on the other side of the traffic barrier.

Mong Kok, a working class neighborhood that feels a world away from the city’s financial center on Hong Kong island, has become one of the movement’s most resilient protest sites. But as the demonstrations near the end of their 6th week, supporters are growing even more divided as they wrangle over what options they have left.

Disagreement between student groups and Occupy Central, which is led by a Hong Kong university academic, have been apparent almost since the protests started. Now, as the occupations drag on—today is their 40th day—other more extreme political groups are starting to fill the void left by protesters who have returned to work or school.

The most well-known among these is Civic Passion, a populist group with an anti-mainland streak—the group wants to protect Hong Kong culture from mainland influences as well as see the fall of China’s Communist Party. Its charismatic leader, Wong Yeung Tat, a media personality and writer recognizable by his trademark white-rimmed glasses, said that the movement should not “scold others or criticize others opinions” and should “avoid internal splits” in an editorial last month.

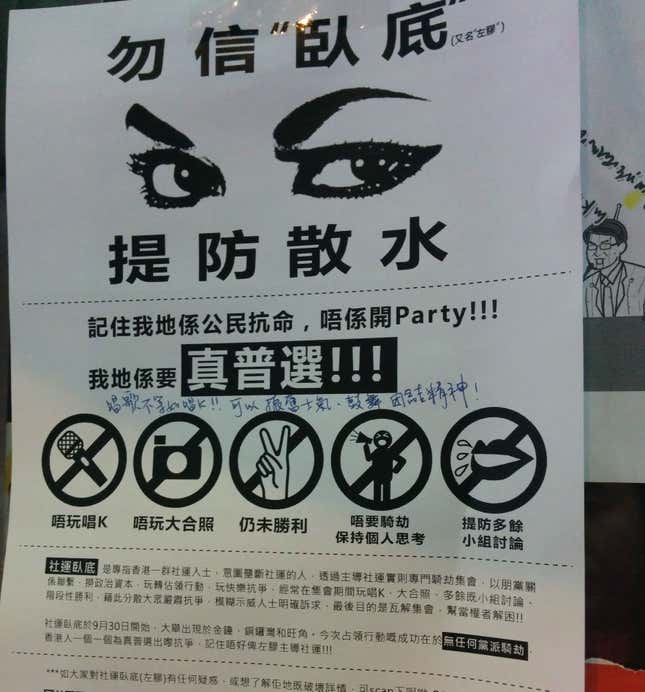

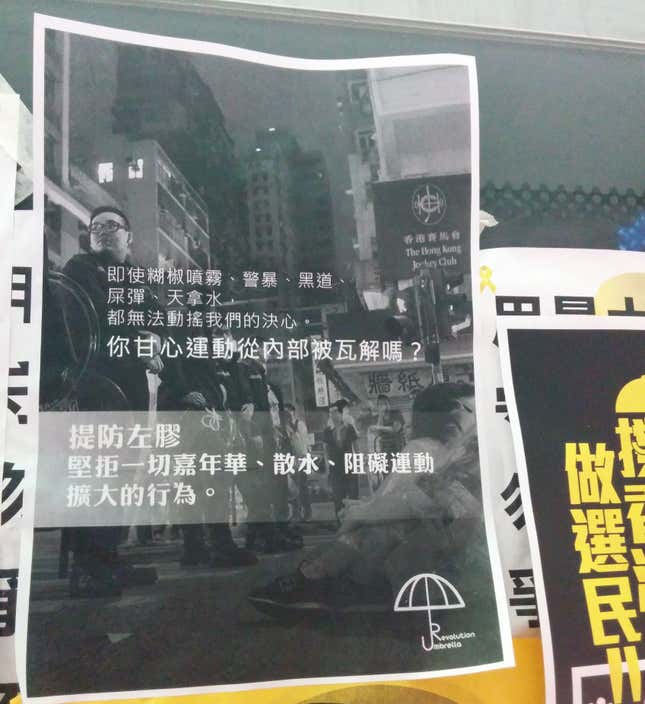

And yet Wong also claims the Umbrella Movement is “no longer under any centralized command,” and his group has criticized student leaders like Joshua Wong as “useless.” Along the western side of Nathan Road where Wong’s group has set up a base, signs are pinned to bus stops and notice boards that call for “defending against ‘left plastics,'” a term that more radical protesters use to describe ineffectual left-leaning liberals.

Sensing division, the Hong Kong Federation of Students, the student group representing the protesters in so far inconclusive negotiations with the government, has been holding “checking groups” where student leaders collect opinions from protesters on the ground. The students’ strategic options are few. The students are asking Hong Kong’s former chief executive to help set up a meeting with Chinese officials, in hopes of overturning Beijing’s decision on electoral reform in Hong Kong—the students have been considering taking the fight to Beijing.

Another idea is to force legislative elections by having Democratic lawmakers resign, opening up their seats for candidates that will campaign on a platforms of direct elections. But critics say the move could lose the Democratic Party crucial seats. The last option is continuing the occupation of the three main roads that protesters have blocked off. For many protesters that’s not a long-term option. “At some point it’s time to go home. You realize you did your best and the government still hasn’t changed,” the protester in Mong Kok says.

Late Thursday on the eastern side of Nathan Road, Civic Passion’s side, protesters—many of them older, compared to the students on the other side—practice self defense, listen to speeches, or play games on their phones. Signs dot their tents that read, ”No photos.” Across the concrete barrier, HKFS student leader Yvonne Leung is speaking through a megaphone with a group of protesters, asking for their opinions on their plans. A passersby asks a woman on the outskirts of the group what the discussion is about. She scoffs and says while walking away, “They think they’re going to Beijing.”