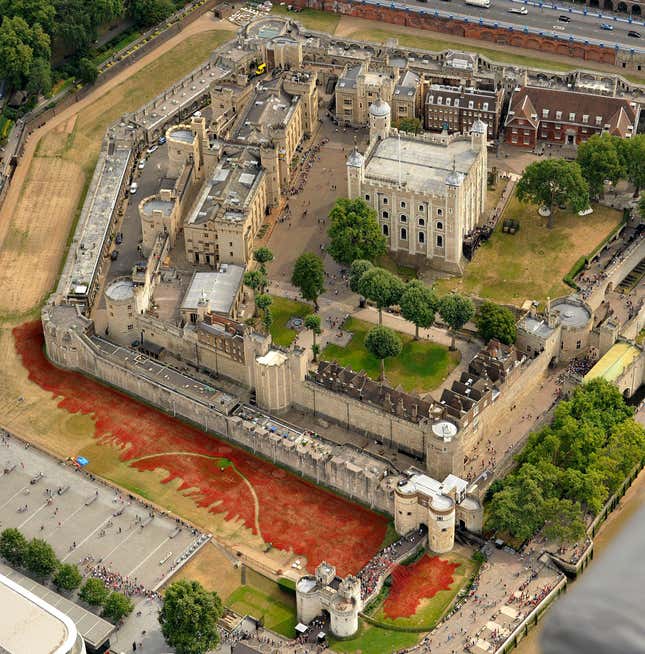

LONDON—Early in August, the Tower of London was transformed into a sea of red ceramic poppies to commemorate the centenary of World War I. The art installation is called Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red, and it has proven astoundingly popular: More than 4 million people are expected to visit it, and the installation has been extended through the end of the month before going on tour across the UK until 2018.

Blood Swept Lands has truly captured the public’s imagination. The area around Tower is generally noisy and crowded with people not used to the British art of queueing. But approaching the site, the masses turn respectful, polite, even somewhat sombre. Demand to see the poppies is so high that floodlights over the West Moat will now be turned on from 4:30am until midnight each day to satisfy demand.

Not bad for an art installation drawing attention to a war with few surviving veterans.

The piece was created by Paul Cummins, an artist specializing in ceramic flowers, with the help of Tom Piper, a stage designer. The inspiration came from the unsigned will of an Derbyshire man who died fighting in Flanders. ”I don’t know his name or where he was buried or anything about him,” Cummins told the The Guardian. “But this line he wrote, when everyone he knew was dead and everywhere around him was covered in blood, jumped out at me.”

The line was, “The blood-swept lands and seas of red, where angels fear to tread.”

Cummins said he believes the angels in his poem refers to the soldier’s children. The art installation honors him and every other British and colonial fighter in the war: There are 888,246 ceramic poppies, one for each soldier that died between 1914 and 1921—underlining that people did not stop dying with the armistice in November 1918.

The poppies were handmade using 400 tons of clay at Cummins’ factory in Derbyshire. He told the Art Newspaper there were around 400 workers, including “metal-makers, rubber part-makers, kiln technicians and many more people making boxes, packing and so on,” who have been working on the project since August 2013.

Cummins said it was important that each poppy be handmade, each ranging between 15 cm and 1 meter tall:

I wanted every flower to be individual, each one representing a soldier. They couldn’t be made in any other way or in any other country. They had to be British. We used traditional techniques to reflect how things would have been made during the war.

The tradition of poppies to mark WWI, by the way, comes from the fighting in Flanders, where the flower was blooming amid some of the most horrific and bloody warfare the modern world had seen. A Canadian soldier and poet named John McCrae wrote the following famous poem, which helped lead to the flower being adopted officially by veterans in 1922:

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

The original site of Blood Swept Lands was a park in London, but Fiamma Montagu, the project’s producer, said ”there wasn’t sufficient security, so we went to Historic Royal Palaces, who immediately liked the idea. Paul initiated the whole idea and paid for it up front, then decided to allocate the proceeds to charity as part of the work.” Around 8,000 volunteers helped “plant” the poppies.

The Tower of London turned out to be quite a fitting location, as the moat was used as the training ground for 1,600 men dubbed ”the stockbrokers’ battalion,” comprised of bankers, lawyers, and others from the city’s financial district. Since the start of the installation, descendants of the men who fought in the Great War have placed pictures of their servicemen parents and grandparents on the railings around the Tower.

Part of the reason, despite the best will of people and politicians, that the project cannot continue indefinitely is that the ceramic poppies are being sold to raise money for the Royal British Legion, which hopes to get £15 million in proceeds. The two installations designed with Piper—the Weeping Willow and the Wave, which depicts flowers pouring like a river of blood out of one of the Tower windows—will remain and then go on tour of the UK.

For his part, Cummins is happy that the exhibition is coming to an end, as he says its temporary existence reflects our short time on Earth. ”The idea was it will only be there for a finite time like we are,” he has said. ”It will be nice to keep it here but it isn’t mine anymore—it belongs to the world now.”