Everyone knows that Russia’s population, consumed by vodka and tuberculosis, has been in catastrophic decline. Just last fall Foreign Affairs’ essay subtly titled, “The Dying Bear,” argued that Russia was rapidly depopulating, that there was no way to halt this depopulation, and that demographic decline would have a number of dangerous side effects such a greater likelihood that Russia, no longer able to man and equip a proper military, would lower its nuclear threshold. Even US Vice President Joe Biden, hardly the most perspicacious man in the world, weighed in with an observation that Russia had a “shrinking population base” and that this meant it would be more likely to bend to American demands. Out on the right side of the spectrum, you can find far more colorful descriptions of Russia’s demographic peril such as writer Mark Steyn’s rather tasteless formulation that “Russian women are voting with their fetus.”

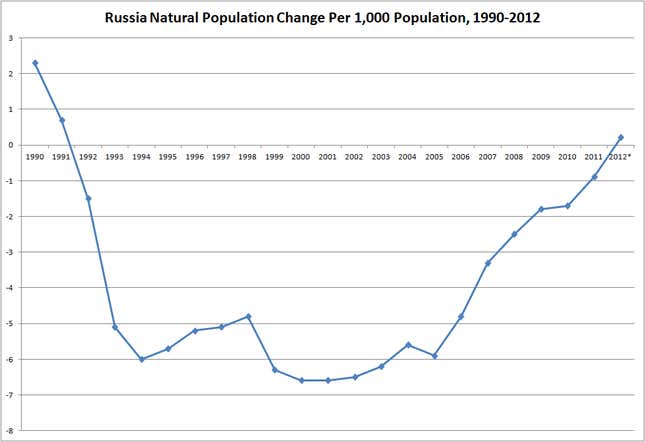

But while the American establishment, left, right, and center, has come to a consensus that Russia is in the midst of an inevitable demographic death spiral, a curious thing happened: things got better. Quickly. Over the past seven years, Russia’s demographics have improved at a rapid clip. As data released today by Rosstat, the Russian state statistical agency, show, Russia is actually on track to record a small natural population increase in 2012. To understand just how dramatic a turnaround this is, it helps to look at a graph of the past two decades:

During the chaos of the 1990’s, as the economy collapsed, living standards fell, and the state was unable to fulfill even its most basic obligations. Russia really did experience a withering demographic crisis. Consumed by insecurity and anxiety, Russians stopped having children and started to die at greatly elevated rates. The health system’s disfunction played a role, but was secondary to a pervasive environment of psychosocial stress, heavy drinking, and poor nutrition. This was a humanitarian disaster on a grand scale that was almost totally unheralded in the West while it was taking place even as many Russians, such as dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, shouted themselves hoarse about the ongoing catastrophe.

However, over the past seven years there has been a decline in death rates from causes like murder, suicide, and alcohol poisoning, and the birth rate has increased. State efforts, such as the much heralded “maternal capital” program which gives almost $10,000 to parents having a second or third child, have had some impact. But most of the improvement is due to economic growth, increased wages, and a generally increased sense of normalcy and stability.

Russia will, like every other country in Europe, face demographic challenges: its population will continue to age, and major reforms to the pension system are clearly needed. But Russia is, thankfully, not in the midst of a “death spiral”—when you account for substantial immigration, its “declining” population has actually been growing for most of the past four years.