Nearly 80% of all US currency in circulation is denominated in $100 bills. (As of June 30, 77%.)

Seems somewhat strange doesn’t it? After all, we find remarkably few of our pockets jammed with those pesky C-notes.

And it’s not just us. Economists acknowledge that at face value, the proliferation of hundreds doesn’t seem to make sense. Writing about the growth of the cash supply as well as the preponderance of $100-dollar bills back in 2010, economist Edgar Feige wrote that the numbers:

“Imply that the average American’s bulging wallet holds 91 pieces of U.S. paper currency, consisting of: 31 one dollar bills; 7 fives; 5 tens; 21 twenties; 4 fifties and 23 one hundred dollar bills. Few of us will recognize ourselves as ‘average’ citizens. Clearly, these amounts of currency are not normally necessary for those of us simply wishing to make payments when neither credit/debit cards nor checks are accepted or convenient to use.”

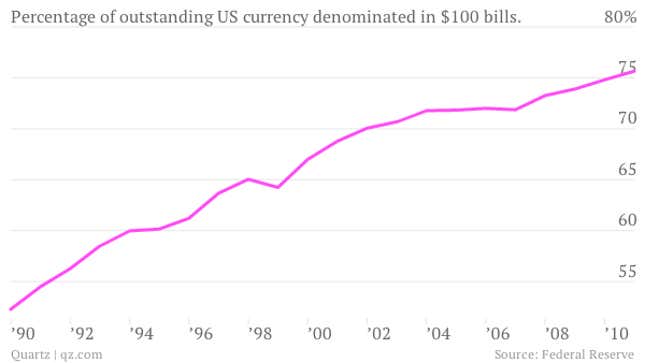

The share of greenbacks denominated in $100 bills has been consistently on the rise for decades. Here’s a look at data going back to 1990, from the Federal Reserve.

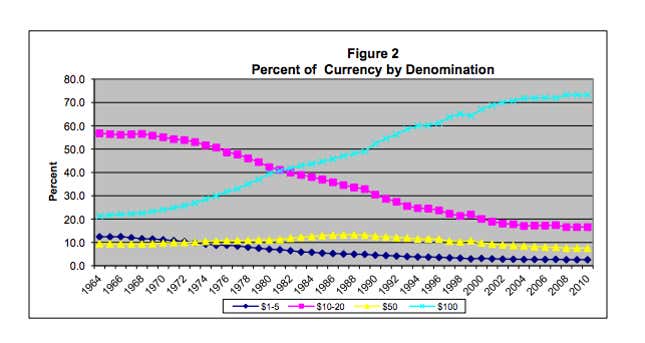

In fact, the trend really seemed to start rolling as far back as the 1970s, according to this chart published in an economics paper by Feige:

So what the heck is going on here? Inflation may have something to do with it—there just weren’t as many things to buy in 1970 that might require one to slap down a $100 bill—but that still wouldn’t explain why their proportion today has nothing to do with what people see in their wallets.

The short answer is that a lot of money is spending a lot of time outside the United States.

The cognoscenti look at the share of $100 bills as something of a proxy for foreign demand for US currency. An overwhelming majority of the $100 bills come from the Federal Reserve Cash Office in New York City, which handles the bulk of foreign shipments of US currency. A typical shipment is a pallet containing 640,000 such bills, or $64 million, according to a recent Fed paper.

Somewhat surprisingly, it’s unclear exactly how much American money is floating around outside the US. Estimates run the gamut. In the 1990s, one high-profile estimate pegged the number at as much as 70%. But more recent estimates hover around 25%-30%.

And while there are plenty of reasons folks outside the US might want to hold dollars, the thinking is that most people are not using these $100 bills to buy milk and bananas. No, most economists seem to believe $100 bills are most often used as stores of value—almost something like mini-Treasury bills that don’t pay any interest. This is especially so in developing countries, where problems with unstable currencies and inflation often mean the purchasing power of local currency gradually—or not so gradually—erodes over time.

The bills might circulate as payments in more developed countries, however. Payments for what? Well, that touches on any number of elements of what has been elegantly named “the informal economy.” That is, the markets that function without the costs (taxes) and benefits (legal protections) of the state. Feige writes:

US currency is a preferred medium of exchange for facilitating clandestine transactions, and for storing illicit and untaxed wealth. Knowledge of its location and usage is required to estimate the origins and volume of illicit transactions. These include the illegal trade in drugs, arms and human trafficking as well as the amount of ‘unreported’ income, that is, income not properly reported to the fiscal authorities due to noncompliance with the tax code.

Large bills in outside currencies are indeed known to be a problem. In 2010, UK exchange offices stopped selling €500 notes, after police officials said 90% of the notes sold in the UK ended up in the hands of organized crime. Doesn’t this present something of an ethical quandary for the US, if its largest bills are the currency of choice for criminals outside the US? It would seem so.

Cynics might point out that on the other side of that ethical quandry is fact that printing and selling money abroad is a remarkably profitable little business for the US government. Yes, that’s right. Like all governments, Uncle Sam earns a profit, known as seigniorage, on the printing of money. And that profit cuts—slightly—the amount the US has to borrow from the public to keep the lights on. Some economists describe foreign holdings of US money as effectively an interest-free loan to the US. Feige writes:

Domestic seigniorage earnings (based on the fraction of U.S. currency held at home) simply represent a redistribution of income from US currency holders to US taxpayers. On the other hand, seigniorage earnings on currency held abroad represent a net transfer of real resources from foreign currency holders to US taxpayers.

Nonetheless, the spread of plastic as a means of payment planetwide seems to be nibbling away at this handy source of revenue. In the 1980s, the US earned a net profit of around $14 billion a year (pdf, p. 35) on seigniorage; by 1999 it was up to $25 billion; by 2010, it was back down to $20 billion. Oh, well—it was never going to be enough to solve the US deficit anyway.