Call it a coup or a revolution—Burkina Faso has finally overthrown its longtime strongman Blaise Compaoré. During his 27-year-long rule, Compaoré’s regime was accused of corruption and nepotism and of violently quelling a student and military rebellion in 2011.

Revolutions now happen in real time and Compaoré’s overthrow was no different. This October, protestors, journalists and politicians used the hashtags #Lwili and #Burkina to live-tweet their way through a chain of events that started with massive street protests and ended with a cellphone video of Compaoré fleeing the country with his convoy of SUVs.

The digital connection between Burkinabé youth activists—who dubbed the protests “Revolution 2.0,”—their diaspora, and supporters in the West led to a flurry of online interest in Burkina Faso.

Images showing streets and squares flooded by demonstrators, many of whom were women brandishing wooden spatulas, a local symbol of gender defiance, were shared thousands of times on Twitter and Instagram.

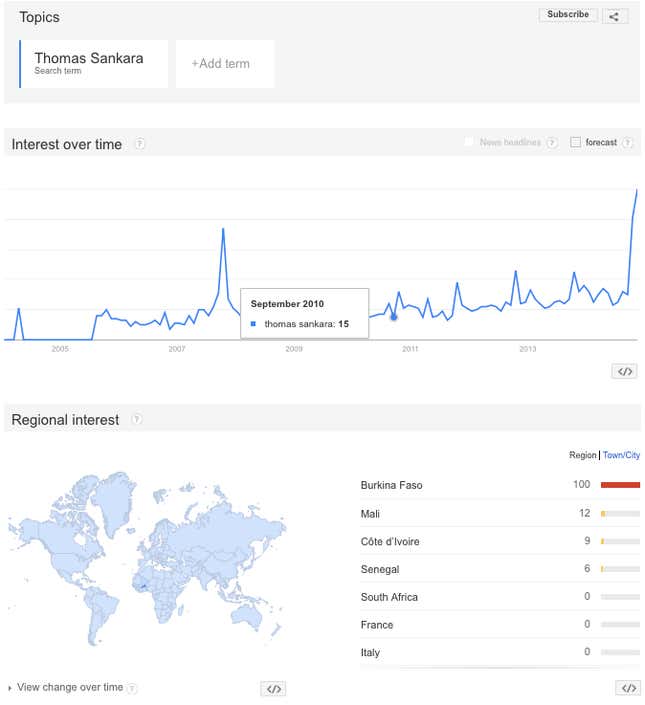

Alongside international focus in Burkina Faso has been a resurgence of interest in the man many protesters credit as their inspiration—Thomas Sankara.

Overthrown and murdered in Compaoré’s 1987 coup, Sankara has long been revered by African nationalists and leftists for his charismatic blend of revolutionary zeal and progressive philosophy. President of the country for four years between 1983 and 1987, Sankara has only a few interviews and speeches attributed to him—yet his legacy is far larger. Today, his message is finding a new, broader of pool of admirers in the social media generation both in Burkina Faso and abroad.

As president, he changed the name of the country from the colonial Upper Volta to Burkina Faso, which means “land of upright people” in an amalgam of the country’s most popular languages. A guitarist, he wrote the national anthem, a stirring ode against neo-imperialism.

And the phrase on the lips of protesters this summer—“La patrie ou la mort, nous vaincrons,” (homeland or death, we shall overcome)—was on the national crest during his tenure.

One of the popular movements behind Compaoré’s recent ouster—Le Balai Citoyen or The Civic Broom movement—was led by two self-professed Sankarist musicians, who spread their message of “sweeping clean” Burkina politics through social media, a number of popular songs, and large political gatherings. In May they held a rally with the political opposition that filled a 35,000 capacity stadium.

[protected-iframe id=”22bcf7c30c94f325b57a2d5fb60dc8ad-39587363-74825215″ info=”d.getElementsByTagName” ]

Sankara was famous for his stance against repayment of African debts and his advocacy of economic self-reliance. Under him, Burkina Faso accomplished massive child immunizations, started a national campaign to fight desertification by planting 10 million trees, banned female circumcision and forced marriage, and had a government with women in high positions.

Feminist activist Minna Salami, one of Applause Africa’s “40 African Changemakers under 40,″ has been writing about Thomas Sankara on her influential Ms. Afropolitan blog since 2010. For her, discovering the works of Sankara was a revelation.

“Like other young women of African heritage—and men as well— I thought, why did I not know about this person?” she told Quartz. “Why are we so many millions of miles away from the vision he had for the African continent?”

It’s unclear what will happen next in Burkina Faso. After seizing power when Compaoré fled, the military agreed to form an interim government that will run the country until elections in Nov. 2015. The new prime minister, former military leader, Isaac Zida has vowed to repatriate Compaoré, stamp out corruption and launch an inquiry into Sankara’s 1987 death.

Since the Compaoré’s ouster, neighboring Togo (#tginfo) and nearby Chad have seen large demonstrations with protestors invoking Burkina Faso as a roadmap to unseating their own long-term autocratic leaders just like the Burkinabé activists credited the movement that ousted Senegal’s Wade before them.

Correction: an earlier version of the article mistakenly stated Sankara’s year of death.